Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

Lot 179

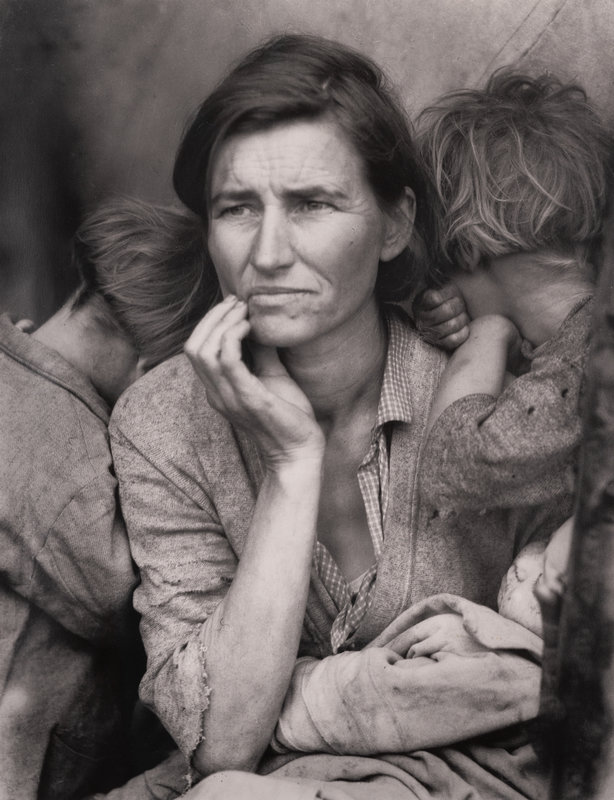

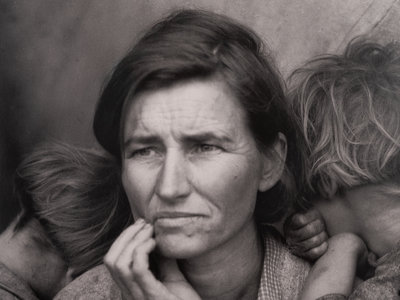

Dorothea Lange

(American, 1895-1965)

Migrant Mother, Nipomo California

, 1936

Sale 1028 - Prints & Multiples

May 12, 2022

10:00AM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$50,000 -

70,000

Price Realized

$31,250

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Dorothea Lange

(American, 1895-1965)

Migrant Mother, Nipomo California

, 1936gelatin silver enlargement print

printed by the photographer or under her direct supervision in Berkeley, ca. 1950's

19 1/8 x 14 3/4 inches.

Literature:

Dorothea Lange: American Photographs (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1994), plate 43

Dorothea Lange: Photographs of a Lifetime (New York: Aperture, 1982, p. 77

The Photographs of Dorothea Lange (New York: Hallmark Inc., 1995), p. 45

Provenance:

Family of the artist, California

Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

Acquired from the above in 2009

Lot Notes:

Dorothea Lange ran a successful portrait studio in San Francisco from 1919 but, by the 1930s during the Great Depression, the growing population of the city's homeless and unemployed moved her to photograph its breadlines instead.

Dorothea Lange: American Photographs (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1994), plate 43

Dorothea Lange: Photographs of a Lifetime (New York: Aperture, 1982, p. 77

The Photographs of Dorothea Lange (New York: Hallmark Inc., 1995), p. 45

Provenance:

Family of the artist, California

Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

Acquired from the above in 2009

Lot Notes:

Dorothea Lange ran a successful portrait studio in San Francisco from 1919 but, by the 1930s during the Great Depression, the growing population of the city's homeless and unemployed moved her to photograph its breadlines instead.

In 1936, the Federal Resettlement Administration (Farm Security Administration) hired Lange to document rural poverty and the plight of migrant laborers in the west. While on assignment in California's San Joaquin Valley, she came across Frances Owens Thompson and her children huddling under a makeshift tent in a camp of destitute pea pickers in Nipomo. The pea crop had been destroyed by freezing rain and there was no work for them. Lange's encounter with the family led to the creation of Migrant Mother, an image that not only appealed to popular sentiment at the time, but also became emblematic of these harsh times. Lange later spoke of the meeting with Thompson in a 1960 interview for Popular Photography:

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She and her children had been living on frozen vegetables from the field and wild birds the children caught. The pea crop had frozen; there was no work. Yet they could not move on, for she had just sold the tires from the car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it."

There are few images as familiar as Migrant Mother in American iconography. It has been reproduced countlessly, on a wide variety of goods from T-shirts to postage stamps. Yet for many years no-one knew who the sitter was or what had become of her. Thompson was finally found in the late 1970s living in a trailer park near Modesto, California, by a local newspaper journalist who persuaded her to give him an interview. Her life had always been one of great hardship. Born Florence Leona Christie, a Cherokee, in a teepee in Indian Territory, Oklahoma, in 1903, she married at 17 and by 28 was widowed with seven children. To support her young family, Thompson worked as a temporary farm hand wherever she could, always just a step away from destitution. "We just existed. We survived. Let's put it that way" she said.At the pea-pickers' camp in Nipomo, Lange persuaded a reluctant Thompson to allow the family to be photographed in order to raise consciousness about the plight of these itinerant workers and possibly secure aid for them. Despite Lange's later claim, Thompson always vigorously denied having sold her car tires to pay for food, supposing that the photographer had either mixed the family up with another, or had elaborated on their story for greater dramatic effect.

Lange's widely-circulated photograph created a sensation throughout the country and established Thompson as a role model for the poor and dispossessed. It also cemented Lange's reputation as a socially-conscious and uncompromising photojournalist. By the time the photograph was published, however, Thompson and her family had moved on and she received nothing for her participation.

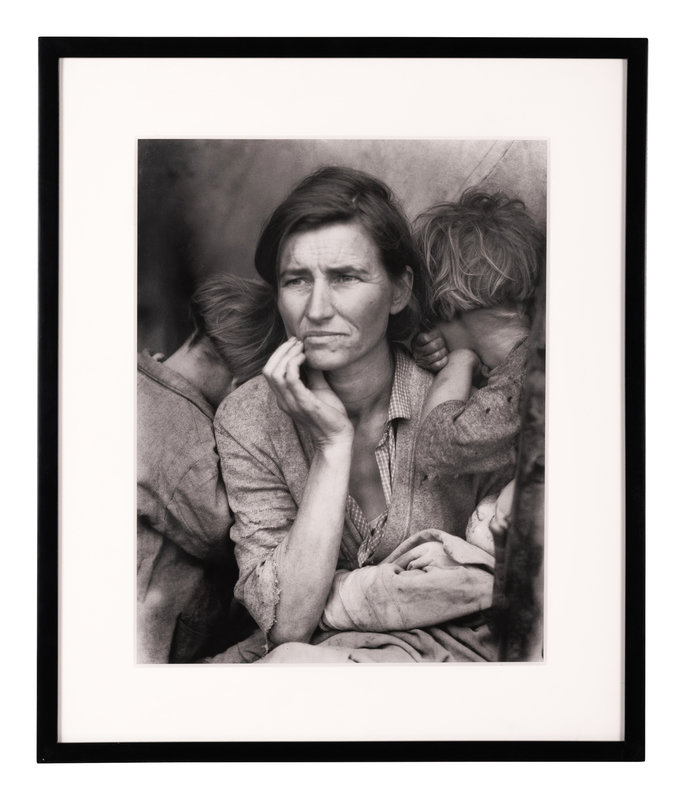

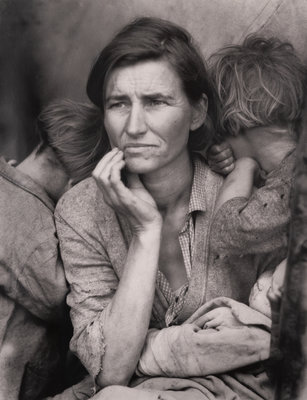

The current lot is a large gelatin silver print made under Lange's direct supervision in the 1950s. Like many prints of this period, the image lacks Thompson's left thumb, which in all very early prints can be seen propping up the flimsy canvas shelter. Lange always found this thumb intrusive and in 1939 instructed her assistant to remove it from the negative altogether. Prints made after 1939 have a ghostly, blurry spot where the thumb once was instead. Thompson's left index finger remained untouched in the background.

FSA Director Roy Stryker, Lange's boss on the project, was concerned by Lange's manipulation of the image, given the documentary nature of the assignment, fearing that this edit compromised the integrity of both. It seems, however, that all but one (the first) of Lange's six exposures of the family were carefully staged to create a more poignant and compelling composition. As a gifted former portraitist, Lange must have been acutely aware that the power of the image depended on Thompson's tragic and heroic figure at its center.

As well as being an extraordinarily rare and important lifetime print of Lange's signature work, this photograph also boasts superb provenance; it was originally part of Dorothea Lange's family collection.