James Joseph Jacques Tissot

(French, 1826-1902)

Portrait of the writer Ouida, c. 1870

Sale 1057 - American & European Art

Sep 27, 2022

10:00AM CT

Live / Chicago

Estimate

$15,000 -

$20,000

Sold for $31,250

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

James Joseph Jacques Tissot

(French, 1826-1902)

Portrait of the writer Ouida, c. 1870

oil on panel

signed J.J. Tissot (lower right)

12 x 16 inches.

We are grateful to Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz for her confirmation of the sitter's identity and preparing this catalogue entry.

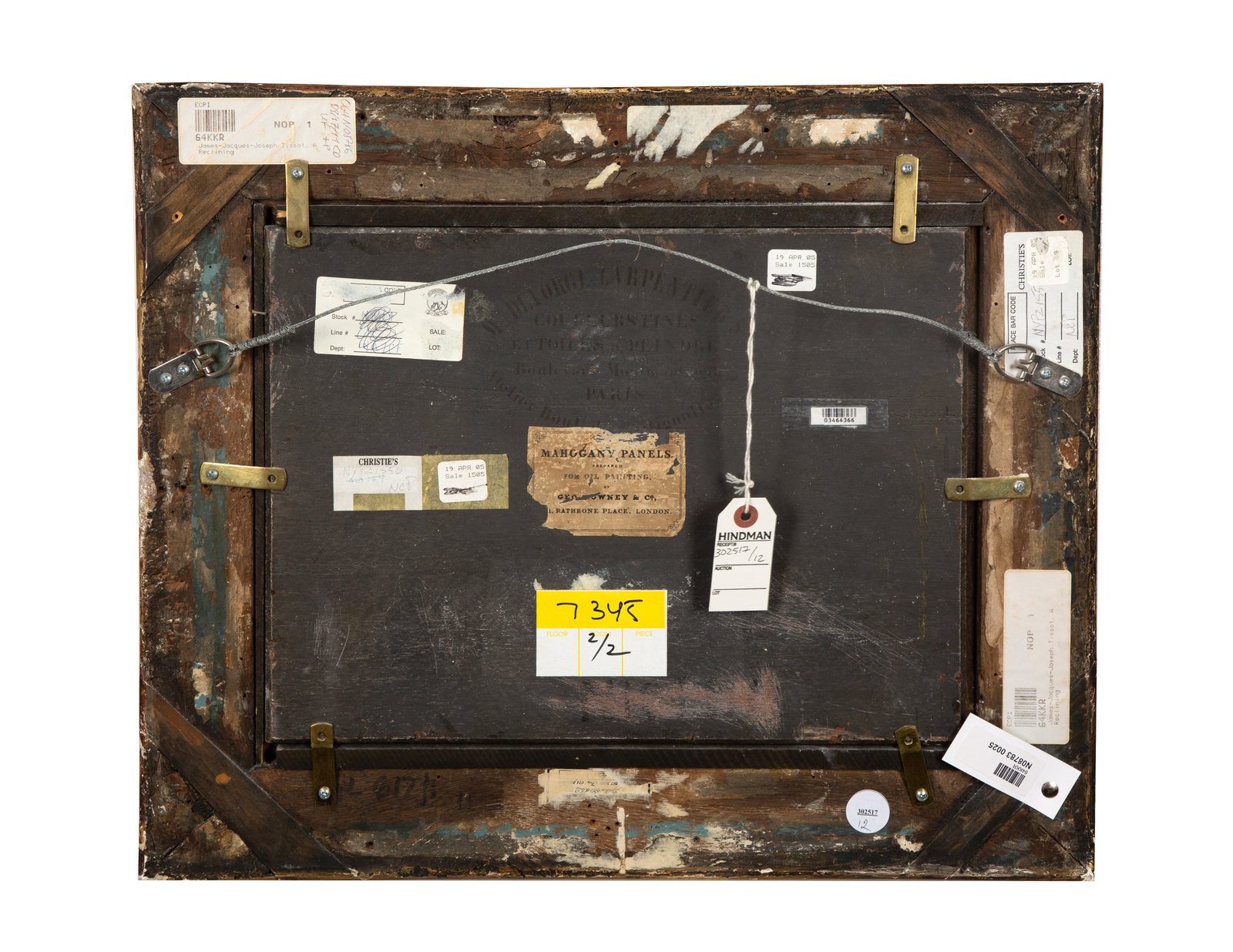

Provenance:

Sold: Christie’s, London, June 3, 1994, Lot 158 (as Femme allongée)

Sold: Christie’s, London, April 19, 2005

Sold: Sotheby’s, New York, 2011, Lot 25, as A Reclining Lady

Literature:

Eileen Bigland, Ouida, the Passionate Victorian, New York, 1951, pp. 64-65, perhaps the portrait referred to p.65

Lot note:

Although documentation identifying this portrait’s sitter is lost, the setting depicted and the sitter’s facial features show it to be Ouida, the Victorian writer, who was a friend of the artist. She enjoyed great international fame and popularity from the 1860s to early 1900s, and has recently been reclaimed by feminists and reappraised as a significant 19th century author.

Sold: Sotheby’s, New York, 2011, Lot 25, as A Reclining Lady

Literature:

Eileen Bigland, Ouida, the Passionate Victorian, New York, 1951, pp. 64-65, perhaps the portrait referred to p.65

Lot note:

Although documentation identifying this portrait’s sitter is lost, the setting depicted and the sitter’s facial features show it to be Ouida, the Victorian writer, who was a friend of the artist. She enjoyed great international fame and popularity from the 1860s to early 1900s, and has recently been reclaimed by feminists and reappraised as a significant 19th century author.

Ouida was the pen-name of Marie Louise Ramé (1839-1908), a name she altered to Marie Louise de la Ramée, although she wanted to be known only as Ouida. The author of twenty-four best-selling novels, fourteen volumes of short stories, five novellas, two volumes of essays, and countless articles on the arts, politics and animal rights, Ouida was most famous for her 1860s ‘sensation’ novels about dashing military heroes and for later novels focused on society behaviour. She was an eccentric character and from late 1866 to summer 1871 lived in an apartment at the Langham Hotel in London. There she would receive business guests during the day in her bedroom, where heavy curtains were drawn against the windows to keep out daylight, and lighting was provided by oil lamps and candles. The novelist would receive guests while sitting in her enormous bed, busily writing. It is this habitual daytime appearance, propped against enormous pillows and illuminated by lamplight, which the anglophile French artist, James Tissot, captures in this portrait of Ouida. The painting is likely the one she refers to in a letter of June 1870 to her continental publisher, Freiherr von Tauchnitz: ‘I am about to have a portrait painted by a celebrated artist,’ she wrote, ‘and this picture will then be engraved’ (Bigland, 1951). The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870, ending in the Siege of Paris and Commune in spring 1871, would have prevented translation of the painting into print by Tissot himself. He was certainly a celebrated artist and visited London in 1870, sometime before mid-July, painting there his famous portrait of the elegant Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (National Portrait Gallery, London), dated 1870. Like the portrait of Ouida, Burnaby is painted on a small, commercially-prepared panel, Tissot’s preferred support for oil paintings made in London during 1870-72. Such panels provided a smooth, even surface to paint on and were easier, and safer, to transport when travelling than canvases.

Tissot, born in north-west France and christened Jacques Joseph, had been called James since childhood and used the name professionally when he became an artist. He was a great lover of England and all things English. From 1859 he had exhibited paintings at the Paris Salon and from 1862 had also exhibited work in England. Tissot was highly regarded as a portraitist and had also been commissioned in 1869 by Thomas Gibson Bowles, editor of the English satirical weekly magazine, Vanity Fair, to draw caricatures of leading European political figures. The portrait of Burnaby was owned by Bowles and probably a gift from Tissot, as the artist did not record its sale. Ouida’s portrait may also have been a gift to her, as its sale is similarly not recorded by Tissot in the notebook of sales he kept from 1857-90. Tissot was very innovative in his portrait compositions, preferring to capture his sitters posed informally, and including settings that give context to the people portrayed, as well as evocative details. On mahogany panels prepared with a painted surface by George Rowney & Co., Tissot brushed overall a warm-coloured brownish glaze to give even background tone, as can be seen at the edges of this painting and in areas behind the pillows. Figure and setting were then painted in deft, rapid strokes of colour. He excelled at painting textiles, ceramics, silverware and jewellery, as seen in this portrait.

Christened Marie Louise, Ouida had preferred to use her second name, and ‘Ouida’ was her lisped childhood version of Louise, adopted by her as a pen-name. It had the advantage, when starting out as a woman writer, of being non-specific as to gender. Her father, Louis Ramé, was a Frenchman, an exiled Bonapartist who taught French for a living in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, but also undertook secret missions and disappeared in 1871 around the time of upheaval in Paris. Ouida’s mother, Susan Sutton, was an Englishwoman, though the author identified herself more with French people than English. She published her first story in 1859 and her novels of the 1860s brought Ouida fame and very good income, which she spent lavishly. Of her escapist novels, an obituary writer would say ‘critics read them with a shrug; the novelist with a sigh; the school girl with bated breath and shining eyes; and bank clerks and lady helps with numerous thrills of envious rapture.’ In Tissot’s portrait there is a thick softback book (perhaps a publisher’s proof), which Ouida has been reading and put down while the artist paints her portrait. There is a bottle of smelling salts on the bedside table, ready to hand, and a small medicine bottle near a silver sugar caddy, with porcelain teacup and saucer beside the brass lamp that illuminates the famous author.

There are two known photographs of Ouida: one taken around 1872 by Adolphe Paul Auguste Beau and engraved by August Weger, showing her in profile with loose flowing hair (on which was based a drawing of 1878 by Alice Danyell, reproduced as a lithograph); and a later, full-face portrait of about 1880 by Elliot & Fry, in which she rests her head thoughtfully on one hand and has hair dressed with a centre parting, which was reproduced on a cigarette card in the 1890s. (A photograph of a young woman in low-cut evening gown, with elegantly dressed hair, which has been used as an illustration of Ouida, is in fact the portrait of an American actress that was wrongly catalogued.) The nose, eyebrows and dark eyes in Tissot’s painting are very similar to those in the two definite photographs of Ouida. Tissot’s painting appears to be the earliest surviving image of the writer. Ouida corresponded with Tissot, inviting him when he visited London in mid-June 1871 to come to her Langham Hotel apartment where ‘some English artists will enjoy the great pleasure of meeting you & seeing your sketches’ (presumably those he brought with him of the Paris siege and Commune). She wrote to him in English, even though she was fluent in French: perhaps Tissot had said he wanted to practice his English. They may have first met some years before 1870, when Ouida visited France with her parents. It has been speculated that Tissot’s 1860 etching, Louise, may represent Ouida, as there is a resemblance, but the poetry couplet he added below the image refers to ‘large blue eyes softer than a cornflower’ and the poet Louise Colet, more likely the subject, was renowned for her blue eyes.

Soon after her 1871 meeting(s) with Tissot, Ouida set out on a continental tour of Belgium, Germany and Italy. She was so taken with Florence that she decided to live there, and remained in Florence until her death in 1908, although she did visit London again several times. Whether she took with her to Florence the portrait by Tissot is unknown. Her lifestyle in Florence was extravagant and she ended up a pauper, her income from writing all going on paying off debts. She was buried in Italy and a memorial to her was constructed in her English birthplace, Bury St Edmunds.

Condition Report

Framed: 18 1/2 x 22 inches.

The physical condition of lots in our auctions can vary due to

age, normal wear and tear, previous damage, and

restoration/repair. All lots are sold "AS IS," in the condition

they are in at the time of the auction, and we and the seller make

no representation or warranty and assume no liability of any kind

as to a lot's condition. Any reference to condition in a catalogue

description or a condition report shall not amount to a full

accounting of condition. Condition reports prepared by Hindman

staff are provided as a convenience and may be requested from the

Department prior to bidding.

The absence of a posted condition report on the Hindman website or

in our catalogues should not be interpreted as commentary on an

item's condition. Prospective buyers are responsible for

inspecting a lot or sending their agent or conservator to inspect

the lot on their behalf, and for ensuring that they have

requested, received and understood any condition report provided

by Hindman.

Please email fineart@hindmanauctions.com for any additional information or questions you may have regarding this lot.