Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

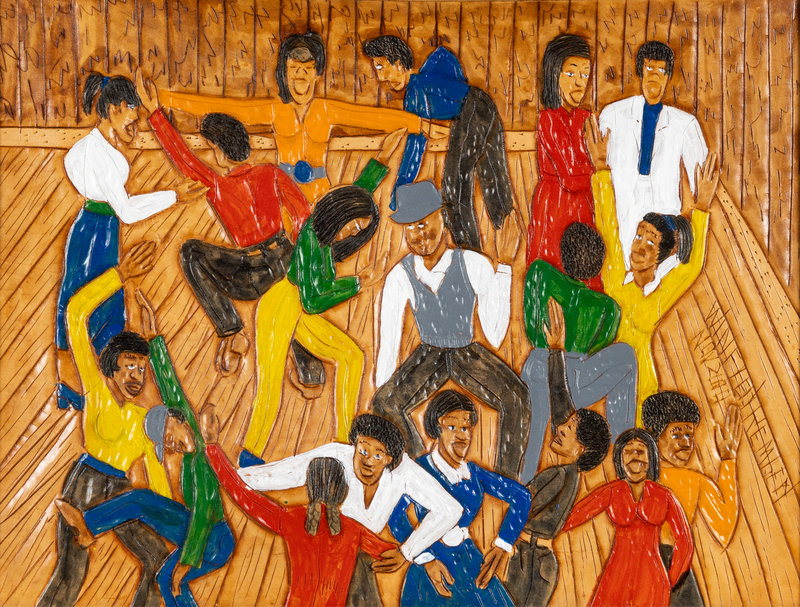

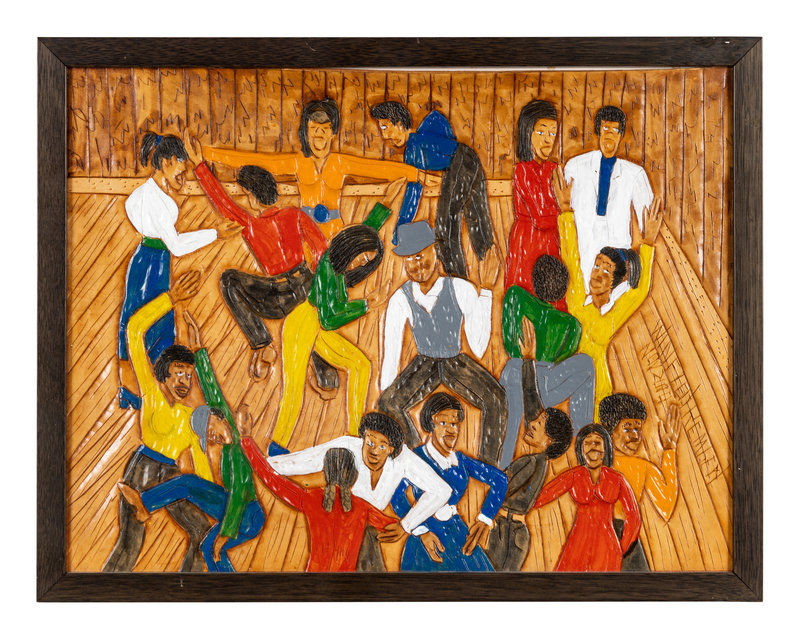

Lot 127

Lot Description

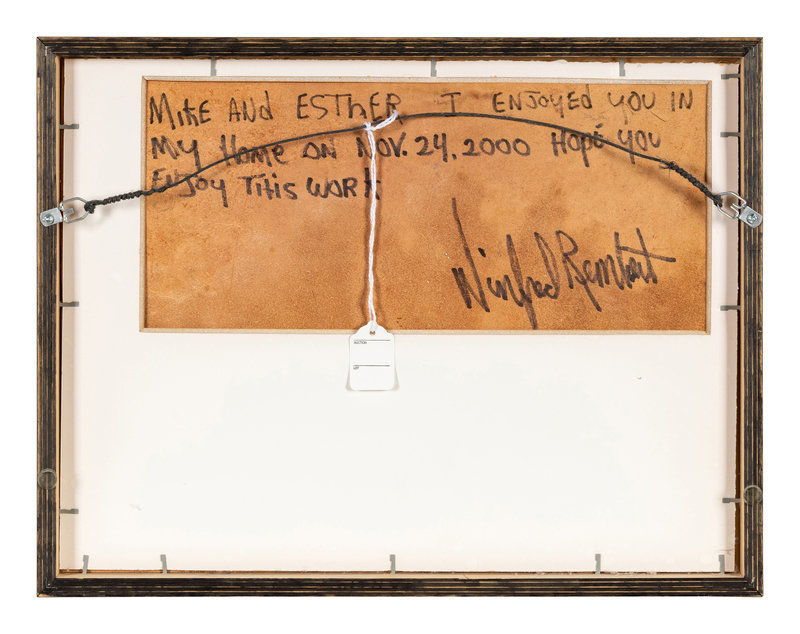

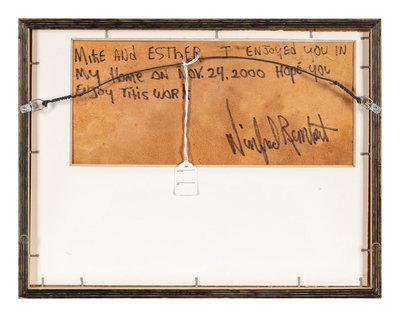

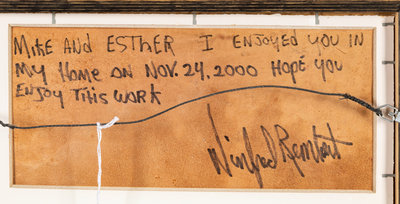

Provenance:

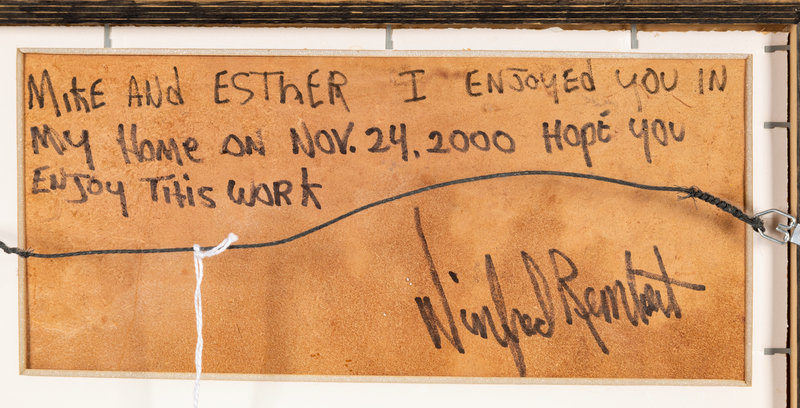

Gifted by the Artist to the present owner in 2000

Lot Essay:

Winfred Rembert: Looking Up

“Leather takes a beating, and whatever you can do with it, it will hold its shape. You can carve it up and it will hold your picture.”

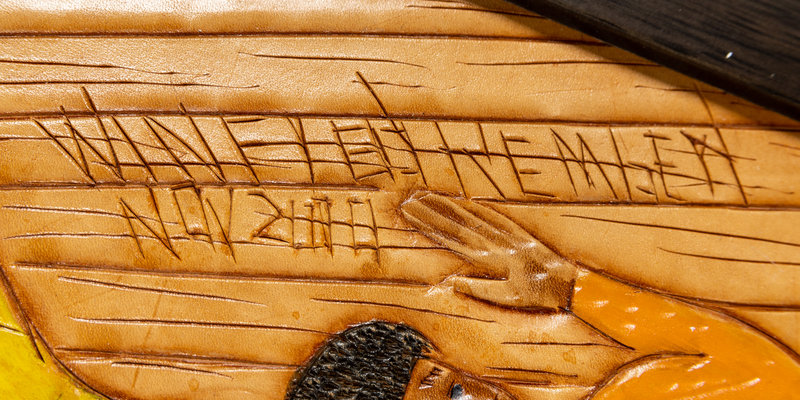

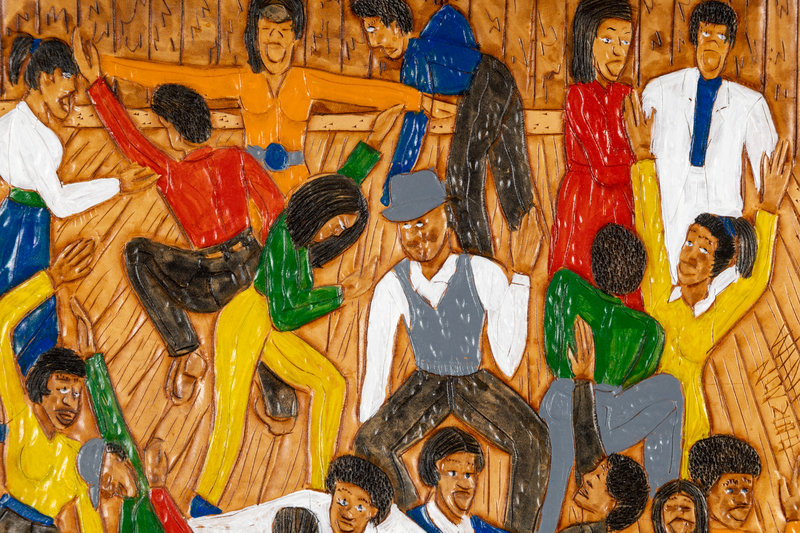

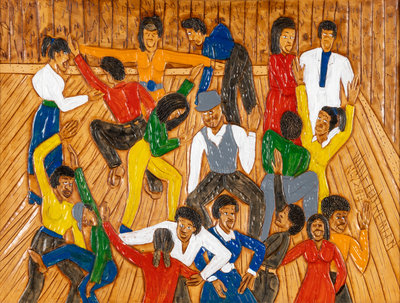

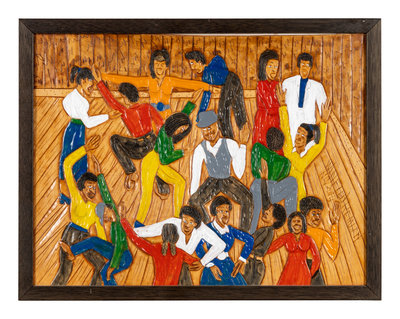

-Winfred Rembert, Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow SouthWinfred Rembert (American, 1945-2021) learned to swing dance by watching couples through a window at a juke joint, an iterant teen on Hamilton Avenue in Cuthbert, Georgia. The experience stuck with him and he would go on to form his own dance troupe, frequently appearing on Rockin’ with the Deuce, an evening program airing on local TV. Juke Joint (2000), is a lively depiction of his dancing days – the natural creasing of the leather gives motion to the figures in the scene, with Rembert only portraying people he knew, giving them their exact gestures and likenesses. Like a single frame from a television show, this scene appears lively and light of spirit, a happy moment among many. Denying Rembert these affections would be doing him a disservice, but so would ignoring the dark structures of his upbringing and eventual adulthood that he was forced to overcome to make such joyful work. As he would be the first to say, it was a wonder he survived.

Rembert was born in Cuthbert, Georgia, and was immediately given away to his great aunt, another scene he would later carve in leather. His mother had fallen pregnant while her husband was in the military overseas, and she was wary, to put it mildly, of his eventual homecoming. His great aunt, whom he called Mama, was a sharecropper, and Rembert's first memories were of the cotton fields, picking up his own sack to fill at 5 years old. School was out of the question, as the demands of his job quickly caused the child to fall behind, delaying his ability to read or write until his teens. Rembert ran away at 13 from the plantation he was raised on, walking for miles back to his mother, only to find her cold and unloving for the rest of his life. His mother did give him something, at least: she still lived in Cuthbert, a place to which he would continually return, and Cuthbert had Hamilton Avenue, the center of local nightlife that would become a galvanizing force for Rembert’s artistic and personal development.

“Hamilton Avenue was just fantastic. It has a hold on me, even now. Being introduced to Hamilton Avenue was the best thing that’s ever happened in my life. […] Hamilton Avenue came into my life and made me a different person. I was able to put the cotton field behind me and never go back. I found something that was so different and so good. A lot of good things have happened to me, but it seemed like Hamilton Avenue was the best. Nothing can match it. Nothing. I walked from one world into another when I came out of the cotton field and discovered all those smiling faces, all those people doing well and not picking no cotton.”

After finding work in a pool hall on Hamilton Avenue, 19-year-old Rembert threw himself into engaging with his newfound community, and with his burgeoning social consciousness came an interest in the Civil Rights movement. Rembert was arrested after attending a protest in Americus, Georgia. After spending a stagnant year in jail without any charges ever being filed against him, he attempted a wily escape, which failed, putting him at the mercy of police officers who locked him in their trunk. A horrifying lynching attempt followed: Rembert was stripped and strung up, tied to a tree by his ankles, and stabbed until one of the several onlookers finally became uneasy and ended the proceedings. Finally at court for the first time, Rembert was sentenced to prison, where he would rotate through facilities and chain gangs.

While working on the chain gang, Rembert first saw Patsy Gammage, the future love of his life. They married in 1974 and moved north to New England, where he found work as a longshoreman on the coast. Rembert had first learned to carve and dye leather in prison, carefully tooling it into the scenes from his past, and began to rediscover his art. At age 51, and with Patsy’s encouragement, the memories were repurposed – now carved, painted, and decorated.

His tooled leather depictions of his life are often brutal and sometimes gleeful – an uncomfortable duality. Juke Joint is one of the happier moments, even signed with the date and occasion the meeting took place, like a diary entry – a careful cataloguing of time from someone who had so little control of his own.

Remarkably, Rembert was never cynical. His tooled leather pictures began to take ahold of the art world in a way he could have never imagined, with his first solo show at York Square Cinema in New Haven in 1998. Others followed – Yale University, then Harlem, then nationwide. He was finally invited back to Cuthbert in 2011 by Andrew College, where the Mayor declared September 18th to be Winfred Rembert Day.

“My homecoming in Cuthbert was different than anything else. The people I knew in that little country town, those people that made my life complete – they still made a difference when I went back there. Being celebrated like they celebrated me, that outplayed everything else that was happening. I left Cuthbert all locked up in chains with a twenty-seven-year sentence. I left there as a jailbird, a nothing, somebody would never be anything in his whole life. I wanted to rectify that. I wanted to go back and show people that I didn’t commit a crime worthy of the time I had served. I wanted to show the people I went to school with, danced with, and played basketball with who I am and what I do. I wanted to tell them that I’m somebody, not a nobody. I didn’t know whether people in Cuthbert knew why I went to jail, or whether they cared, until I showed up on that day, forty-six years later. I found out they weren’t looking down on me. They were looking up.”

Winfred Rembert died on March 31, 2021; a nationally renowned artist surrounded by his family. Hundreds appeared at his funeral to celebrate his legacy, which lives on in his works.