Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialists

Lot 379

Sioux Twisted Pipe Stem with Catlinite Bowl, Believed to Belong to Sitting Bull

Sale 1053 - Native American Art: The Lifetime Collection of Forrest Fenn, Part I

Jun 9, 2022

10:00AM ET

Live / Cincinnati

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$60,000 -

80,000

Price Realized

$125,000

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Sioux Twisted Pipe Stem with Catlinite Bowl, Believed to Belong to Sitting Bull

PREMIUM LOT

Additional registration documentation is required to bid on this lot, and online bids will not be accepted. Please contact [email protected] to arrange for telephone bidding.

AUCTIONEER'S NOTE: Although this is purported by many to be Sitting Bull’s pipe, some have suggested that the evidence is inconclusive and needs further review. Forrest certainly believed that it was. In the absence of further provenance, we urge prospective bidders to weigh the evidence presented and bid accordingly.

fourth quarter 19th century

simple T-shaped bowl; twisted stem having bands of tacked decorations; red pigment within grooves of twist

overall length 26-1/2 inches; length of stem 19 inches; length of bowl 9 inches x height 4-3/5 inches

Provenance and Possible Line of Descent

Sitting Bull

The Quimby Family, Niles, Michigan, ca 1884

Sold by an “Elderly Couple” from Niles, Michigan, early 1970s

Janine Fentiman and John Alward, co-owners of the First Peoples Museum, Allen, Michigan (now closed) 1970s-2003

Joe Rivera, Morningstar Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico (2003)

Forrest Fenn, Santa Fe, New Mexico (2003)

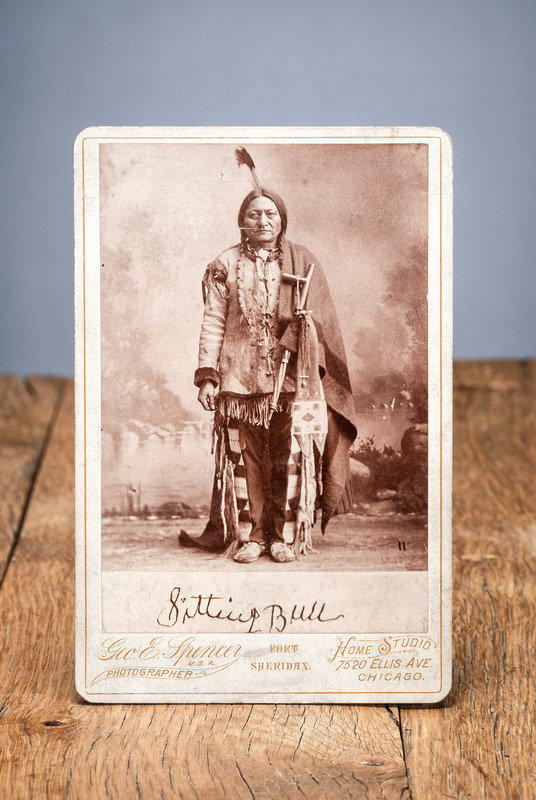

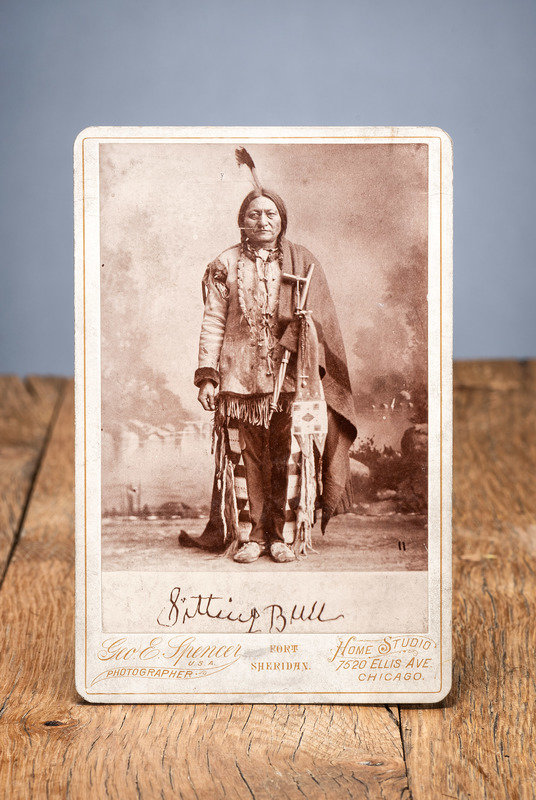

This pipe and distinctive stem are accompanied by extensive documentation which supports an attribution to the Hunkpapa Lakota Chief Sitting Bull (ca 1831-1890). Foremost are historical photographs depicting Sitting Bull holding the pipe bowl and stem matching the one offered here. These historical photographs are the prima facies evidence that Sitting Bull and the pipe were historically related. The provenance of the pipe is not unbroken, however. A possible – and very plausible - explanation of how the pipe found its way from Sitting Bull’s hands to the Niles, Michigan, area where it was purchased in the 1970s is offered, but cannot be positively proven.

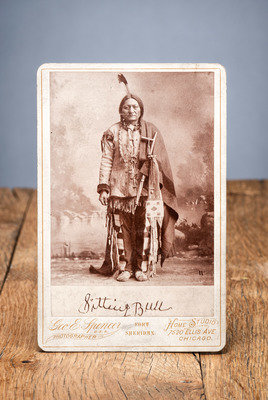

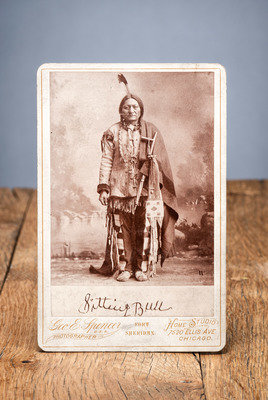

The Palmquist & Jurgens Cabinet Photographs of Sitting Bull and the Fenn Pipe

Following his surrender at Fort Buford, Dakota Territory, on July 19, 1881, Sitting Bull achieved near-celebrity status and was widely photographed. Photographers were eager to obtain his image and market it to an American public hungry for a likeness of one of the most renowned Native Americans of his age. By the early 1880s, Sitting Bull “knew how to earn money by selling his photographs and by autographing almost everything people would buy” (Lindner 2005:2). Over the next decade he sat for a number of studio photographs, and in many held a pipe, none of which are the same (Ibid).

Studio images taken during Sitting Bull’s visit to St. Paul, Minnesota, on March 14, 1884, show the Lakota leader in various poses, and in possession of a distinctive pipe. The occasion was well-documented at the time (Harris 2015: 13-18). At least a dozen glass plate negatives were exposed at the St. Paul studio of Alfred Palmquist and Peder Jurgens, and several were ultimately marketed showing Sitting Bull holding a large catlinite pipe and twisted stem decorated with tacks. Harris (2015) indicates that the visit was hardly accidental. The Hunkpapa holy man entered into a contractual arrangement whereby he gave Palmquist and Jurgens the exclusive right to the negatives for a period of a year and would receive cash and a number of the cabinet cards for personal use as part of the bargain. When Sitting Bull toured with Buffalo Bill in 1885, he entered into a similar agreement with the Canadian photographer William Notman.

The possibility exists that the pipe depicted in the Palmquist and Jurgens portraits was merely a studio prop, though the pair are not noted for their photographs of Native Americans. Indeed, their portraits of Sitting Bull are the only Palmquist and Jurgens photographs of a Native American with which we are familiar. Their stock and trade were portraits of average citizens; given this circumstance it is unlikely that a Native American pipe was simply “on hand” at the time of Sitting Bull’s sitting.

Nelson (2003:6) cites contemporary newspaper accounts describing Sitting Bull’s attire in St Paul. An audience with the local press found him wearing “all the beaded magnificence which befitted his rank.” Another indicates he wore a buckskin shirt, with a white shirt on the outside, leggings, moccasins, and an overcoat. At an appearance with the press at the Merchant’s Hotel, he was described as cleaning a pipe “three and a half feet long with the face of an Indian carved at one end.” This clearly is not the pipe depicted in the studio portrait, but rather a calumet type favored by Great Lakes peoples a generation or more earlier. More often than not, these long-stemmed pipes were considered sacred property of a clan or similar corporate group and held in trust for ceremonial use. Often these long-stemmed calumets were kept in sacred bundles overseen by a single individual. The pipe and its storage bag held by Sitting Bull in the Palmquist and Jurgens photograph is of a size and style meant for personal use.

Sitting Bull and The Horace B. Quimby Family

While interned at Fort Randall in 1881-82 Sitting Bull became friends with Captain Horace B. Quimby (1843-1883), the post quartermaster, his wife Martha “Jennie” Quimby (1845-1896), and their young daughter Alice (1877-1947). Martha commissioned Sitting Bull to make a series of pictographs documenting his life, and when the family left for Fort Snelling, Minnesota, in November 1882, they took the drawings with them (Armstrong 1995).

Captain Quimby died while serving at Fort Snelling in February 1883. According to an obituary for his daughter Helen Quimby Montague (1875-1903), the family moved to Niles, Michigan “one year after the death of her father.” Martha Quimby and her children remained there for the rest of their lives. This timeline provides the possibility that members of the Quimby family might have visited with Sitting Bull in March 1884 during his St. Paul visit and received the Fenn pipe as a gift.

Historical evidence provides a precedent that Sitting Bull made gifts of pipes to White acquaintances, probably to establish or cement a beneficial relationship. On his 1881 journey from Fort Buford to confinement at Fort Randall, for instance, he gave a pipe to hotel proprietor J.D. Wakeman perhaps as a gift for his hospitality during Sitting Bull’s visit to Wakeman’s Bismarck hotel. Another pipe bearing Sitting Bull’s autograph was gifted to Mrs. William Harmon, Sitting Bull’s interpreter during his stay in Bismarck (“The Last Years of Sitting Bull,” State Historical Society of North Dakota, 1985:18).

There is little question that Sitting Bull owned – and gifted -- numerous pipes over the course of his life. By the time of his final surrender, he was acutely aware of his celebrity status, and recognized that his image, autograph, and personal items were in demand by collectors. In addition to the pipes noted above, another pipe bearing his autograph was owned by the English explorer Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904) and was sold at Christie’s London in 2002 (“The African Sale Including Henry Morton Stanley Collection, Lot 138). In 2010 Cowan’s Auctions sold a pipe collected in 1881 by James Sadler who served in the 11th U.S. infantry near Fort Peck, Montana, that retained an affidavit attesting to a Sitting Bull ownership (“American Indian Art” September 10, 2010, Lot 406). Finally, Heritage Auctions sold a pipe bowl presented by Sitting Bull to Richard “Diamond Dick” Tanner, in 1889 with impeccable provenance (Grand Format Political and Americana Auction 6035, Lot 47285).

At Alice Quimby’s death in 1947, the Sitting Bull pictographs commissioned by her mother were donated to the Fort St. Joseph Historical Association Museum in Niles (now the Fort St. Joseph Museum part of the Niles History Center). The drawings were first described in 1955 when they were noted as being one of “several interesting memorabilia of Sitting Bull” that had been donated to the museum (Praus, 1957: 1). Unfortunately, these other items were not described or otherwise enumerated. Recent correspondence with the museum failed to discover any additional Sitting Bull items beyond the pictographs still in their collection, while at the same time acknowledging rumors to the contrary.

Recent Provenance of the Fenn Pipe

The Fenn pipe is accompanied by a 2003 letter of provenance from former owners Janine Fentiman and John Alward of Allen, Michigan, stating: “This pipe was brought to our museum [The First Peoples Museum] in the early 1970’s. We purchased it from aa [sic] elderly couple whose family lived in the Niles, Michigan area. It had been in their family for a number of years… The pipe was sold to us with no attribution. It was not until years later that we acquired the photograph of Sitting Bull holding this pipe.”

Later in 2003 Santa Fe collector and dealer Joe Rivera purchased the pipe from Fentiman and Alward, who in turn sold it to Fenn.

After acquiring the pipe, Fenn pursued research into the Sitting Bull attribution. Fenn commissioned high-resolution digital images of the pipe from period photographs and compared them to the pipe offered here. The results of his findings were published in the 2006 book Sitting Bull’s Pipe: Rediscovering the Man, Correcting the Myth by Kenneth B. Tankersley, Ph.D. and Robert B. Pickering, Ph.D. The book explains how, through the technique of photo superimposition, wood grain patterns could be closely examined, size and shape could be determined, and tacks notches could be assessed. Ultimately, the authors concluded: “Through the process, no morphological discrepancies, or lack of matching tack placements or notch locations were revealed. With virtual matches on all morphological points and no evidence to the contrary, we must conclude that the Fenn pipe and the pipe in the Sitting Bull pictures are the same….”

Pipe accompanied by research documenting the provenance of the pipe and photographic techniques used to substantiate the Sitting Bull attribution. Also accompanied by a copy photograph of Sitting Bull taken by Palmquist & Jurgens at the 1884 studio session on a George E. Spencer period mount and four D.F. Barry cabinet cards showing Sitting Bull’s family and cabin.

References Cited

Anonymous

1985 “The Last Years of Sitting Bull.” Exhibition Catalog, State Historical Society of North Dakota.

1985 “The Last Years of Sitting Bull.” Exhibition Catalog, State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Armstrong, William J.

1995 “Sitting Bull and a Michigan Family: Legacy of an Unlikely Friendship.” Michigan History Magazine, Jan./Feb. 1995, 28-35.

1995 “Sitting Bull and a Michigan Family: Legacy of an Unlikely Friendship.” Michigan History Magazine, Jan./Feb. 1995, 28-35.

Diedrich, Mark.

2003 “Sitting Bull and His 1884 Visit to St. Paul. A ‘Shady Pair’ and an Attempt on His Life.” Ramsey County History, Volume 38, No 1: 4-12.

2003 “Sitting Bull and His 1884 Visit to St. Paul. A ‘Shady Pair’ and an Attempt on His Life.” Ramsey County History, Volume 38, No 1: 4-12.

Harris, Leo J.

2015 “Long Ago Snapshots. When Sitting Bull Was Photographed in St. Paul.” Ramsey County History, Volume 50, No. 2: 13-18.

2015 “Long Ago Snapshots. When Sitting Bull Was Photographed in St. Paul.” Ramsey County History, Volume 50, No. 2: 13-18.

Lindner, Markus H.

2005 “Family, Politics and Show Business: The Photographs of Sitting Bull.” North Dakota History, Volume 72, No. 3 and 4: 2-22.

2005 “Family, Politics and Show Business: The Photographs of Sitting Bull.” North Dakota History, Volume 72, No. 3 and 4: 2-22.

Praus, Alexis

1955 “A New Pictographic Autobiography of Sitting Bull.” Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Volume 123, No. 6.

Tankersley, Kenneth B. and Pickering, Robert B.

2006 Sitting Bull’s Pipe: Rediscovering the Man, Correcting the Myth. Wyk, Germany: Tatanka Press.