Lot 26

Equal parts social scientist, revered professor, institutional critic, and skilled artist, Howardena Pindell (b. 1943) has been able to engage her own past life experiences to examine the larger structures and institutions of the art world and her place therein, exploring and exposing themes of racism, feminism, and regeneration through abstraction.

It all comes back to a circle. In an interview from October 2020 in The New York Times, Howardena Pindell recalls being drawn to the form -- a recurring theme in her artistic practice -- which she had first “experienced as a scary thing.” At a root beer stand with her father as a child, she noticed red dots stuck to the bottom of their mugs; the dots were markers of which glassware was appropriate for use by nonwhites in Jim Crows’ America.

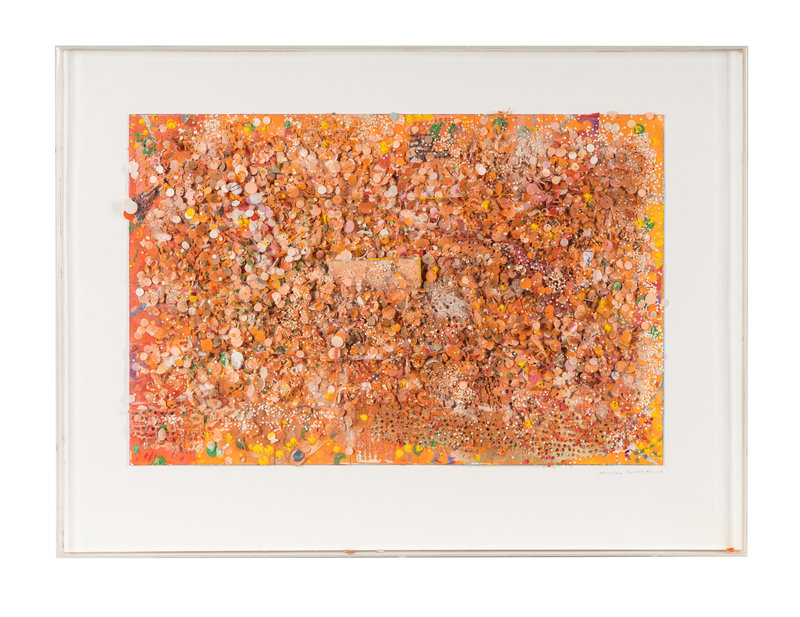

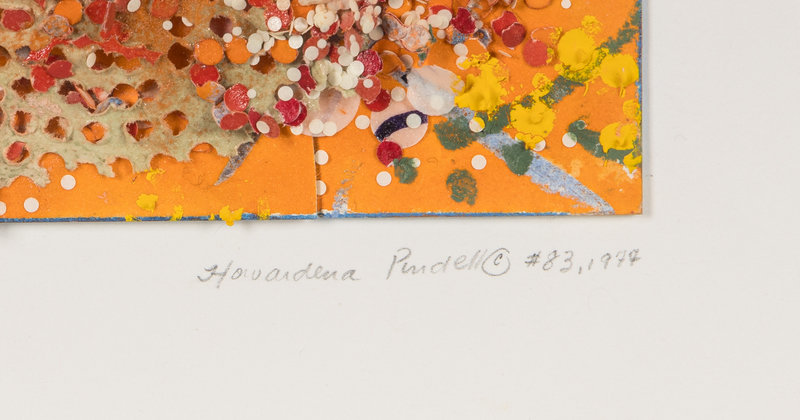

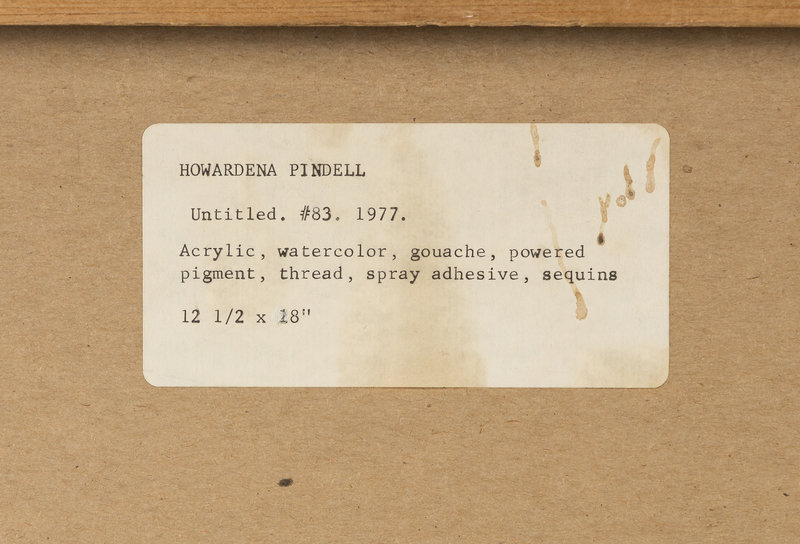

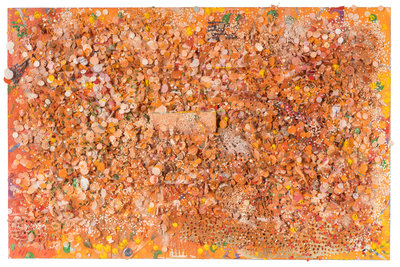

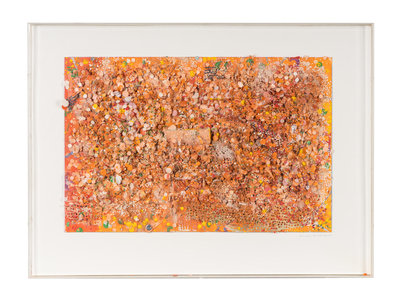

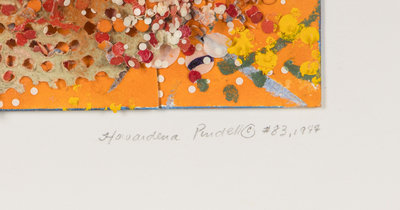

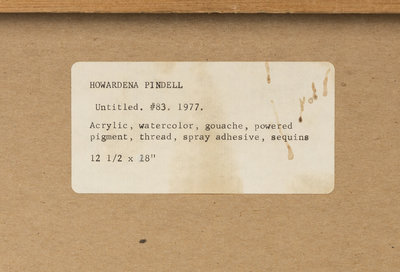

These circles, originally acting as a symbol othering her, would later make their way into Pindell's work where she would reclaim the form as her own, enveloping her artistic practice. After a childhood in Pennsylvania with an aptitude for the arts, she received her BFA from Boston University, and then an MFA from Yale University, which introduced her to abstraction. Kensington Series #3 (1974) and Untitled #83 (1977) are both excellent early-career examples from Pindell, removed from her earliest figurative training and demonstrative of the beginning of the process that would inform her entire oeuvre. Canvases are first cut into strips and sewn back together, cartographically, before painting or drawing on the surface. Then, dots (or “chads”) are cut from the paper with a hole punch and dropped onto the glue-prepped canvas, while the remaining punctured paper serves as a conduit to squeeze paint through, layering the materials together, as we see in Untitled #83. Pindell plays with space on the canvas and the absence of space in the paper stencil, the ordinariness of a hole-punch, and the idea of what constitutes a painting. Sometimes, as seen in Kensington Series #3, the chads are scrawled with rune-like symbols, a reference to her fascination with the coding and rituals present in African sculpture. Other times, they are almost buried under color and texture.

Pindell moved to New York following her MFA program and began working in the Arts Education Department at the Museum of Modern Art, though her personal practice would remain of the utmost importance to her. She stayed at MOMA for the next 12 years, working through the ranks from exhibition assistant to curatorial assistant, to finally achieving the distinction of becoming the first black woman to be a curator at the institution. Outside of working hours, her inclusion in the 1972 Annual Exhibition: Contemporary American Painting, Whitney Museum of American Art only fueled her passion. Kensington Series #3 (1974) and Untitled #83 (1977), both created following her Whitney show, are testaments to her commitment to her art.

A more metaphorical but nonetheless circular obsession dominates Pindell's practice, that of persistent cycles of destruction and recreation. She is dismantling and then recreating the canvas, perforating then repurposing the paper, a three-dimensional form of pointillism. Continuing her artistic preoccupation of connecting her artwork to her life experiences, Pindell herself has had to endure the physical and emotional process of regeneration: a horrific car accident in 1979 left her with injuries and short-term memory loss. Her work helped her recover as she began to incorporate biographical imagery into her style, resuscitating canvases and mapping her own memory.

Clearly no stranger to duality, Pindell, a lifelong academic and curator, has spent as much time critiquing institutions as she has inside them. Her studio practice was not her only focus – the underlying racism she experienced in the art world informed her related political action. Over 7 years at MOMA, Pindell collected information from art institutions and galleries in New York state about their representation of nonwhite artists and designers. Her findings – that 54 out of the 64 surveyed institutions represented 90% or greater white artists – were published in the March 1989 issue of ARTnews. Pindell also co-founded A.I.R., the first artist-centered gallery concentrating on providing women a non-commercial space to curate and show work. She also organized a show through A.I.R. titled The Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the US, reflecting on her own experience with tokenism and racism even within the feminist movement.

Her activism continued in the years following her accident. Pindell wrote letters about racism and social issues to institutions, signing them “The Black Hornet,” and continued her demographic surveys of museum exhibitions and gallery rosters across the state. She then co-founded a cross-generational black women’s artist collective called Entitled: Black Women Artists, which has grown to international proportions, supported by her traveling and lecturing.

Among a litany of other accolades, Pindell received a Guggenheim Fellowship for painting in 1987, two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, and honorary doctorates from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Parsons School for Design. Pindell retains a teaching position at Stony Brook University and had her first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom in 2022. So far, she has not -- and will not -- slow down on her course of constant regeneration: of her own life and health, her artistic practices, and her hope for the restructuring of art world institutions.