Lot 66

Dr. Andreas Neufert has confirmed the authenticity of this work.

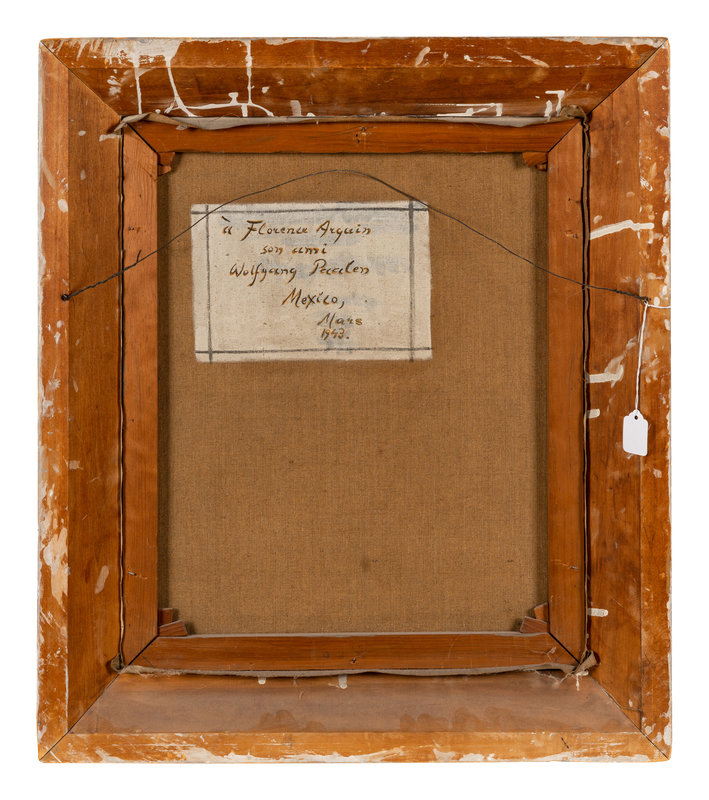

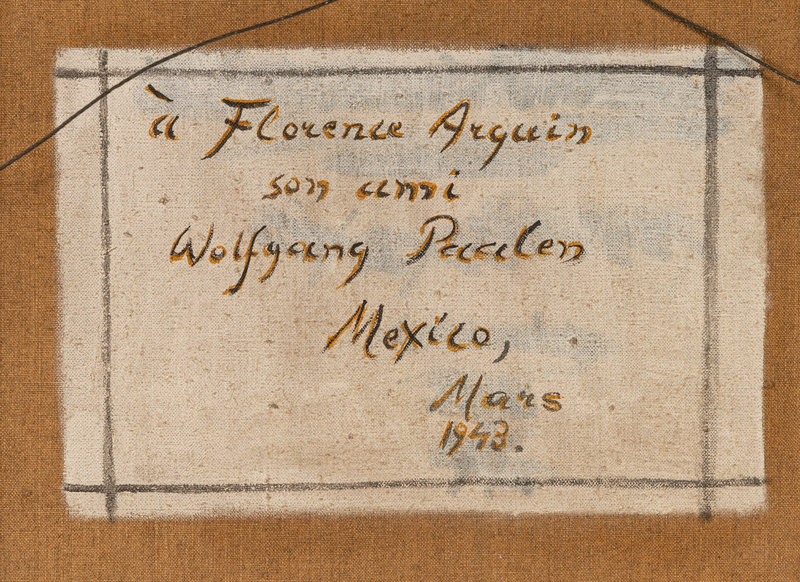

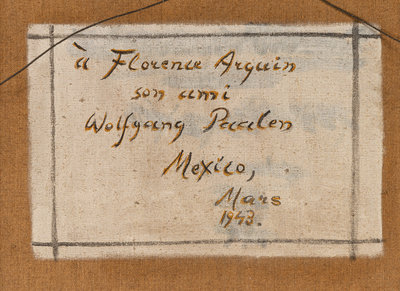

Provenance:

The Artist

Florence Arquin, gift from the Artist

Sam A. Williams, husband of the above

Thence by descent to the present owner

Lot Essay:

Scenes for a Sorcerer (You Never See the Witches)

The roster of our Figuratively Speaking sale reads like a veritable Who’s Who of some of the key players of the twentieth-century Mexican avant-garde—Wolfgang Paalen, Alice Rahon, and Diego Rivera, among others—as collected by Florence Arquin, the noted collector, critic, educator, and celebrated artist in her own right. Arquin, though born in New York, spent much of her life and career in Chicago, Mexico, and traveling through Latin America, employing her experiences as an artist, a friend, and confidant of important artists in Mexico such as Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, and her travels to champion the study of Mexican and Latin American art in the United States. Hindman is pleased to offer these works from the Florence Arquin Collection, many of which feature gifts from her circle of friends that, in addition to emphasizing the intricacies of the social web of this artistic community, are relics from crucial moments in their careers. This is particularly clear in the works offered by Wolfgang Paalen and Alice Rahon— who—from Parisian beginnings among the vibrancy of the Surrealist movement to the fertile influences of the Americas—are emblematic of the chaotic and romantic development of the art world in their time.

Born in 1904 in Chenecy-Bullion, France, Alice Marie Yvonne Philppot would become Alice Paalen and later Alice Rahon, adopting her mother’s maiden name. She was sometimes born in 1912, or in Brittany, where she summered as a child, or in any number of places in any number of years. It’s fitting, then, that the 2021 anthology of her poetry transcribed in English by Mary Ann Caws is titled Shapeshifter. Rather than a loss of identity, her character's fluidity mirrors her little-known yet lasting impact on some of the most influential figures in art history and her multidisciplinary, spellbinding career.

At age three, her right hip fractured, and then her leg broke at twelve, causing much of her childhood to be confined to a cast in relative isolation. The solitude wasn’t an issue for her avid imagination and only further fueled her hunger for books and stories of mythology. Her family moved to Paris in 1920, and she met the artist Wolfgang Paalen on a trip to Corsica in 1931.

Paalen was in Corsica with a dear friend, Swiss photographer Eva Sulzer. Paalen and Sulzer met after Paalen’s painful rejection from the Academy in Berlin. He was ultimately undeterred from becoming an artist; having grown up surrounded by his father’s collection of Old Masters paintings and under the tutelage of painter Leo von Konig, his deep appreciation for the subject had been instilled from an early age. Although Paalen was a year her junior, it seemed he had lived several lifetimes by the time he met Rahon. Formerly distinguished upper-class members of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, his parents separated after his younger brother died suddenly in an insane asylum following a homoerotic affair, presumably of suicide. His mother’s increasingly bipolar disposition worsened as the Wall Street crash of 1929 drained the rest of their fortune. Finally, his older brother Rainer shot himself in the head with a pistol in front of him. Rainer miraculously survived, but Paalen’s personal and artistic development had been forever altered in this decade of family tragedy.

Paalen and Rahon fell deeply in love in Paris, marrying in 1934. Perched cautiously in the years between the wars, Paris was bohemian heaven, with André Breton at the helm of the burgeoning Surrealist movement. Paalen was already among this circle and brought the vivacious Rahon along with him; she quickly befriended Miró, modeled for Man Ray in Harper’s Bazaar, and began designing hats for Schiaparelli. Éluard nicknamed her L’Abeielle Noire (the black bee) for her deep brunette hair, and Picasso took her as a lover before Paalen harshly objected.

Breton officially invited the couple to join the Surrealists in 1935. Around this time, Rahon began to paint, scraping the paint from Paalen’s palettes to make works inspired by the ancient wall paintings in Altamira, Spain, that they had visited at Miró’s bequest.

Deeply inspired by her travels, the couple returned to Paris, where Breton encouraged Rahon to publish her first book of poetry: A meme la Terre (On Bare Ground), printed by Editions Surrealistes -- a limited edition each with an engraving by Yves Tanguy. She would go on to publish two additional books of poetry before deciding to devote herself entirely to painting.

At the same time, Breton was encouraging another artist: Frida Kahlo. After meeting in Mexico through Leon Trotsky, the Soviet revolutionary, he arranged for her first solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1938. After its success, he invited her to Paris for another exhibition the following year. Kahlo arrived in Paris to find that Breton had yet to clear any of her paintings for customs, nor did he actually still own a gallery; a last-minute effort from Duchamp managed to bring together a show, albeit less successful than her previous. The trip was not without its victories, however -- a purchase from the Louvre made Kahlo the first Mexican artist in their collection, and the doyennes of the Parisian art scene welcomed her warmly -- including Picasso, Miró, Schiaparelli, and Rahon. Despite Breton’s insistence that Kahlo’s work was Surrealist, she rejected this label, writing to a friend after her show of "this bunch of coocoo lunatics and very stupid surrealists" who "are so crazy 'intellectual' and rotten that I can't even stand them anymore.” Though the canonical categorization of Kahlo’s work is frequently debated, she was not the only one who felt this way about the defining characteristics of the Surrealist movement – a growing skepticism had begun to haunt Paalen as an ideological shift began to lead him to reject the hold of Freud’s rigid theories.

Rahon and Kahlo were fast friends, with a mutual understanding of their physical childhood traumas and struggles with mobility and their childlessness as women – and women artists, no less. As political unrest loomed, Kahlo invited Rahon and Paalen to stay with them in Mexico City, an offer that was quickly accepted.

Paalen, Rahon, and their close friend and patron Sulzer set off for New York, intending to head directly to Mexico but changing course to the Northwest after being intrigued by native artworks after a chance encounter at a gallery. Meandering down the West Coast, Paalen, Rahon, and Sulzer were profoundly affected by local artists, with Paalen and Rahon continuing to be drawn to totemic and indigenous works and Sulzer likewise influenced by the vast landscapes. Finally, at the end of 1939, the three of them settled into a home Kahlo and her husband Rivera had rented for them in the San Angel section of Mexico City, directly next to their home, Casa Azul.

Upon the Paalens settling in Mexico City, Duchamp wrote intermittently to Peggy Guggenheim and Julien Levy, passionately promoting the work of his friend Paalen:

Dear Julien, P. S. to my recent letter: Do you know Paalen's work? I suppose that you have seen some reproductions. Among the young Surr[ealists]'s, he ought to come out – he paints scenes "for" a sorcerer (you never see the witches). All this to hope that you might show him in N.Y.

Levy was impressed and arranged an exhibit for Paalen in New York. It was well attended, including Pollock, Gottlieb, and Motherwell. One notable absence, however, was Trotsky. Though an introduction was frequently encouraged, Paalen refused, accusing his friends of “pseudo-religious paternal fixations of Surrealists, who didn’t dispose of the means to find other ways out of the crisis Marxism left in their minds than to find a new political father.” This repudiation was to become another marker of Paalen’s dissatisfaction with Surrealism.

He announced his public separation from the group and divorced himself from Breton in 1942 with the publication of the first issue of DYN, an art magazine centered on philosophical art theory with scathing criticism of Surrealism and all it stood for.

Though only six issues of DYN were produced between 1942 and 1944, the publication was profoundly influential as the center of the art world transitioned from Surrealism to Abstract Expressionism following the end of the second World War. With Paalen as editor, the magazine included poems from César Moro, photographs and paintings from Florence Arquin, writings from Henry Miller and Anais Nïn, art from Henry Moore, and the contributions of many others.

Rahon’s painting career began to achieve widespread recognition during the DYN years, with her first solo show at Galeria de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City in 1944. She would frequently exhibit in North America and Europe for the remainder of her life. Her personal works – gifts to friends and pieces in honor of them – most aptly illustrate the magical and indescribable parts of this catalytic time in history and art. Just as she was Eluard’s L’Abeielle Noire, she became Kahlo’s jirafa (giraffe) for her long legs and large brown eyes. Rahon, in turn, memorialized Kahlo in her painting Ballad for Frida, dedicated to “Frida aux Yeux d'hirondelle” (Frida in the eyes of a swallow), inhabited by scenes from their friendship and animal talismans from their years together – owls, birds, cats, and of course, giraffes. It’s with great pleasure that we present in this sale several gifts to Florence Arquin from both Rahon and Paalen, tokens of their affection and markers of their development as artists.

Rahon gave Arquin two works: Le Chat (1943) and Untitled (1946). Le Chat (1943), a personalized drawing inscribed pour Florence son amie Mexico, comes to life with lines that seem to vibrate off the page, both detailed and fantastically obscure. Cats, familiars to the sorcerers of Surrealism, snake in and out of the photos Arquin took and carefully preserved in her scrapbook from her time with Kahlo, Rivera, Paalen, and Rohan. Untitled (1946) is colorful and topographical, with a note of the genuine tenderness between them: in the lower right corner, after the dedication, the word cariñoso is inscribed – caring.

Paalens’ gifts are equally intimate and demonstrate the breadth of his skill as an artist. Two untitled works from 1943 are each emotive and meticulous: the first with swirls of color and movement, the second stormy and reflexive. A third piece, Untitled (1947), is an excellent example of the influence of his environment and interest in indigenous culture, with thin lines of gouache carefully painted on an indigenous Mexican Amate paper.

The years surrounding these exchanges were tumultuous for the couple; through Rahon’s career taking flight and the buzzy years of DYN, they ultimately decided to divorce in 1947.

Rahon would become a Mexican citizen and create screenplays for ballet and film. On the night of the opening of her exhibition at Galeria Pecanins in Mexico City in 1969, she fell and fractured her right hip again, leading her to retreat to a life of relative isolation. This time, she denied any medical intervention, remembering the pain of her childhood. Her continued isolation (save for a few guests, including Sulzer) contributed to the increasingly younger art world overlooking her work, despite her role in developing Mexican art and her influential circle of friends. Her final solo exhibition was in 1986, and she died the following year at a nursing home in Mexico City after refusing to eat. History all too often lets the careers of female artists retreat to the shadows of their male counterparts. Still, Rahon was a force of nature, and with the recent reconsideration of the art world may finally be getting her due.

Paalen’s prolific career continued, and he eventually made amends with Breton, who acknowledged that any criticism of Surrealism that he had was valid. He became increasingly interested in archaeology and contributed to ideas of the matrilinear social structure of ancient societies in Mesoamerica. Paalen’s genius never dampened, but his bipolar disposition made it increasingly difficult for him to function, while his obsessive collection of indigenous artifacts started attracting rumors of illicit activity. The last years of his life were spent in an old house and studio in a small town in Morelos, Mexico, where he was supported by his close friends Gordon Onslow Ford and Sulzer. He was found dead of a gunshot wound to the head in 1959.

Though Rahon and Paalen’s relationship was at times tempestuous, their connection – and that of their circle of friends – left an indelible mark on the art world. Arquin’s careful preservation of these works allows us a look inside the inner life of the avant-garde. The gifts are, in a way, a complete picture of the couple, if only for a moment: offering the full spectrum of color and darkness, form and lack thereof, image and anxiety, during a time when their own lives were rapidly changing shape.