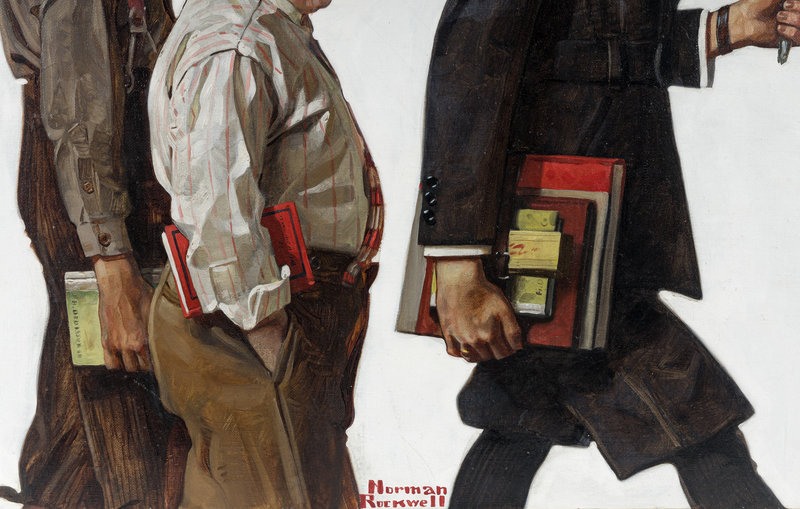

This lot is a study for the cover of The Country Gentleman published on June 14, 1919.

Literature:

Mary Moline, A Chronological Catalog of the Artist's Work, 1910-1978, Indianapolis, 1979, fig. 1-23, p. 17 (magazine cover illustrated)

Laurie Norton Moffatt, Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue, vol. I, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, 1986, no. C50, pp. 20-21

Lot note:

Painted in 1919, when Norman Rockwell was just 25 years old, Only One More Week of School and Then… was made for the June 14th cover of Country Gentleman. Although the young artist would go on to create covers for Life Magazine and The Saturday Evening Post throughout his career, he only produced paintings for Country Gentleman from 1917 to 1922. These playful covers centered around the adventures (and misadventures) of Cousin Reginald Claude Fitzhugh, a know-it-all city boy, and his country cousins, Chuck Peterskin and the spirited Doolittle brothers. The characters were first introduced in the August 25, 1917, issue of the magazine, with Cousin Reginald usually depicted as the unwilling butt of his cousin’s practical jokes.

Only One More Week of School and Then… is representative of Rockwell’s light-hearted, charming narratives that feature children. Rockwell’s ability to render the universally understood emotions of young boys, ranging from misery to delight, is on full display here. The upturned, sprightly face of brown-nosing Reginald, who firmly carries in one hand his schoolbooks and with the other, a bouquet for Teacher, contrasts sharply to the downcast, petulant demeanors of his bumpkin cousins, who are miserable at the thought of another week of school before summer vacation. The next and last painting in the series after the present work, Vacation!, swaps the emotions of the boys, with a despondent Reginald trailing behind a jubilant Tubby and Rusty.

Completed early in the artist’s career, the present painting also demonstrates the more expressive and painterly execution that characterizes Rockwell’s work from the late 1910s to early 1930s, before he adopted photography into his technical process. Even without the aid of a camera, the naturalistic detail with which the three boys are carefully rendered–from Reginald’s immaculate suit to the tattered straw hats of the other two boys—reveals the artist’s ability to capture the varied glory of America’s youth. It is through these keen observations that Rockwell was able to create scenes that resonated with his audience, and what ultimately made him one of the most commercially successful artists of the 20th century.