Provenance:

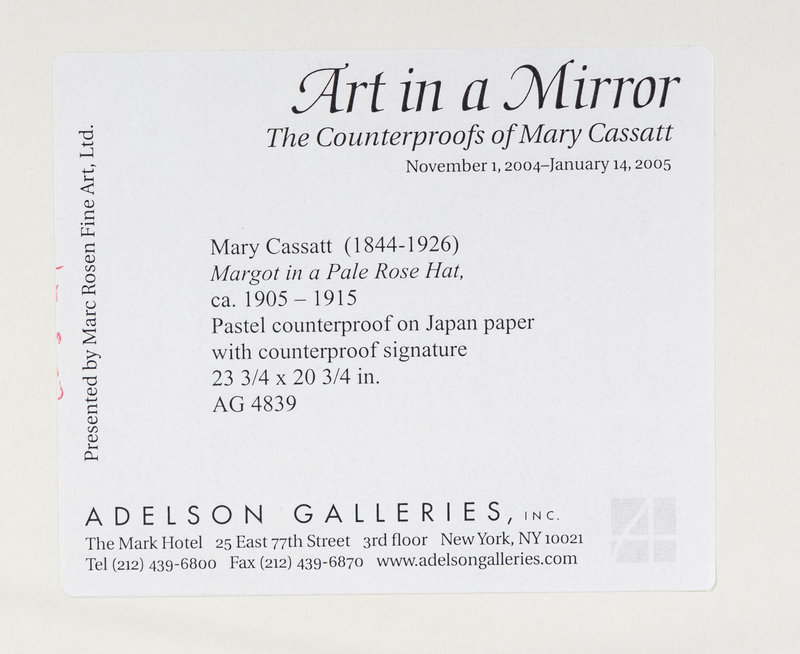

Marc Rosen Fine Art, Ltd. and Adelson Galleries, New York, by 2004

Exhibited:

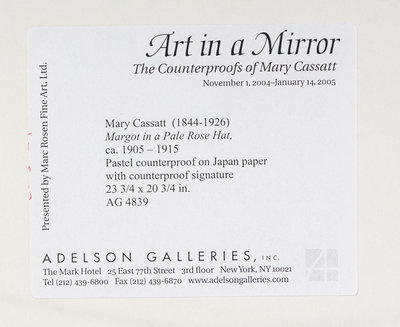

New York, Adelson Galleries, Art in a Mirror: The Counterproofs of Mary Cassatt, November 1, 2004 - January 14, 2005, no. 28, p. 91, illus.

Lot note:

In addition to her extensive work in oil, Mary Cassatt also excelled at the printed medium, especially favoring etching and drypoint and ramping up her production during the 1890s. Her Parisian dealer, Ambroise Vollard, became instrumental in her interest in printmaking. He noticed the high appeal of prints, which were perceived as a bridge between fine art and popular trends, and saw an opportunity: while large productions of prints would sell well, he insisted on connoisseurship and artistic vision as well. It is no surprise, then, that Vollard also championed Cassatt’s production of pastel counterproofs, approximately between 1889 and 1913.

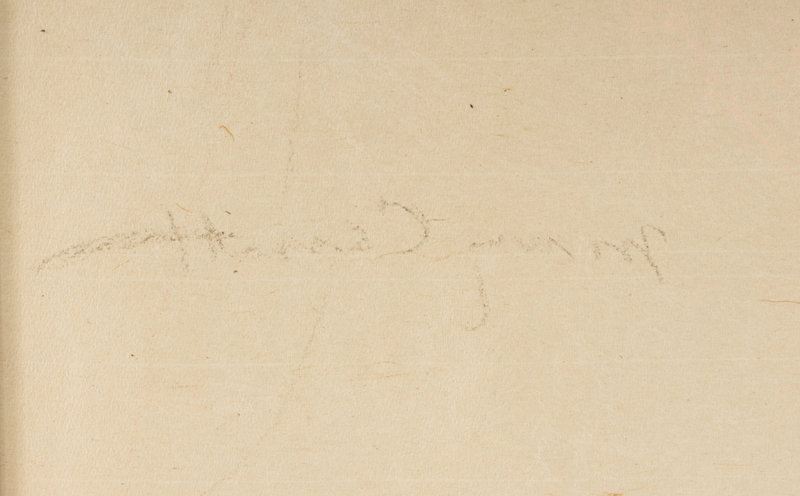

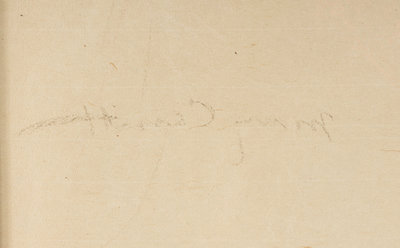

A counterproof is created by applying a damp sheet of paper to the surface of a work in pastel before rubbing or running it through a press, resulting in a mirror image of the original. It is not an exact mirror, however, since the image is rendered in flatter and softer tones. The pastel medium, which fell out of favor with the advent of Romanticism, became fashionable again with the Impressionists, as it allowed for subtle palettes and airy visual effects. Renoir and Degas, Cassatt’s close friend, are also known to have produced pastel counterproofs.

In 2004, Adelson Galleries curated “Art in a Mirror,” a landmark exhibition of Cassatt’s pastel counterproofs, shedding light on this little-known medium and practice by the artist. The exhibition recorded more than 130 counterproofs, from 67 pastels, and a substantial number of counterproofs are believed to be the only remaining trace of the original pastel. Among the counterproofs offered here, only Young Woman Reflecting (lot 55) and Head of Adèle (No. 4) (lot 58) are from known pastels listed in the Breeskin catalogue raisonné, while the rest are from pastels that are unaccounted for.

Though technically derived from pre-existing original works, Cassatt’s counterproofs are arguably works of art in their own right, not mere reproductions. Jay E. Cantor, in his essay “Vollard is a Genius in his Line” published in the Adelson exhibition catalogue, speculates that she likely viewed the medium as a worthy creative experiment: the counterproofs “offered an occasion for innovative reworking. Since the image was reversed, it became, in effect, an entirely different and original work to be confronted on its own term” even though “there is no clear evidence of the degree to which [they] may have been used in this way.” (p. 18). Stylistically, the counterproof process further flattened the image and amplified the evocative, subdued, ethereal tones already displayed in the pastel works. These features, reminiscent of the symbolist aesthetic of the time, especially in the Vollard circle, make Cassatt’s counterproofs a distinct body of work within her oeuvre.

The imagery of motherhood and early childhood is recognizably personal to Cassatt, and the present selection offers a glimpse into her characteristic handling of the subject. As argued by Pamela Ivinsky in her “After Impressionism: Cassatt’s Counterproofs and her Later Career,” also featured in the exhibition catalogue, her rendering of motherhood emphasizes its engrossing element, with the use of the profile and of the maternal gaze directed at the child, not at the viewer. It is a depiction imbued with utmost sensitivity and intimacy, making the maternal bond intangible, nearly lost to viewers as it resides strictly in the space shared by the absorbed mother and her child. The immaterial depth of the maternal bond reflects the diaphanous aesthetic of the image, coalescing in one gesture the narrative and artistic elements of Cassatt’s work.