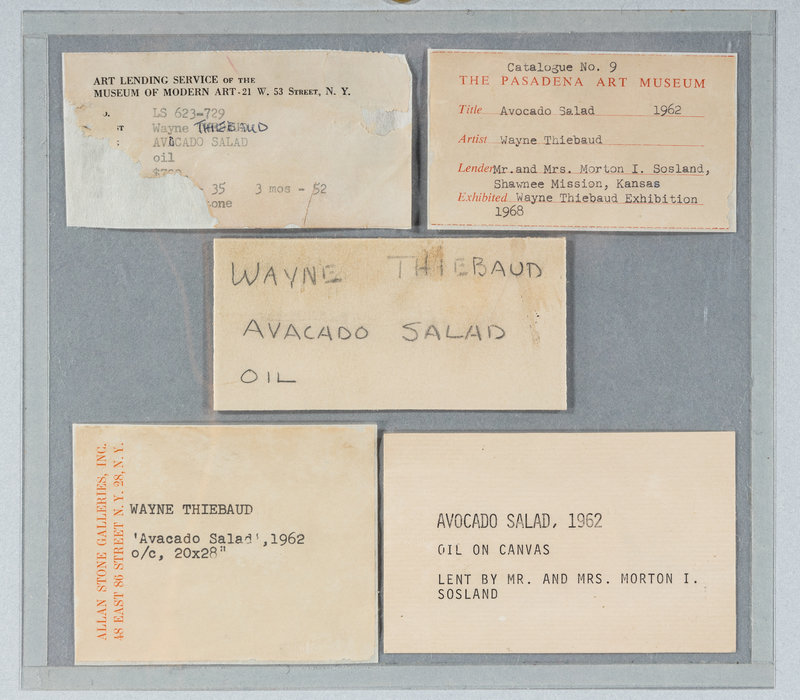

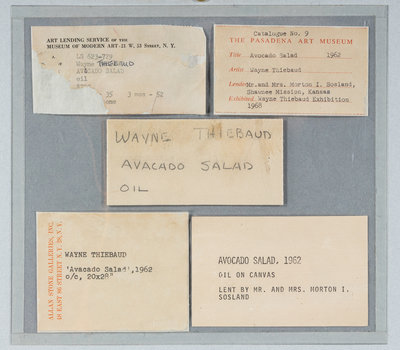

Provenance:

The Museum of Modern Art, Art Lending Service, New York

Lent to the above by Allan Stone Galleries, Inc., New York

Acquired from the above by Mr. and Mrs. Sosland in 1968 (or before)

Exhibited:

Pasadena, California, The Pasadena Art Museum, Wayne Thiebaud, February 13 -March,1968; Minneapolis, Minnesota, The Walker Art Center, April 1 - May 5, 1968; San Francisco, California, The San Francisco Museum of Art, May 23 - June 23, 1968; Cincinnati, Ohio, Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center, July 8 - August 11, 1968; Salt Lake City, Utah, Utah Museum of Fine Art at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, September 22 - October 27, 1968, cat. no. 9

Lot Essay:

Wayne Thiebaud and the Taste for Avocados

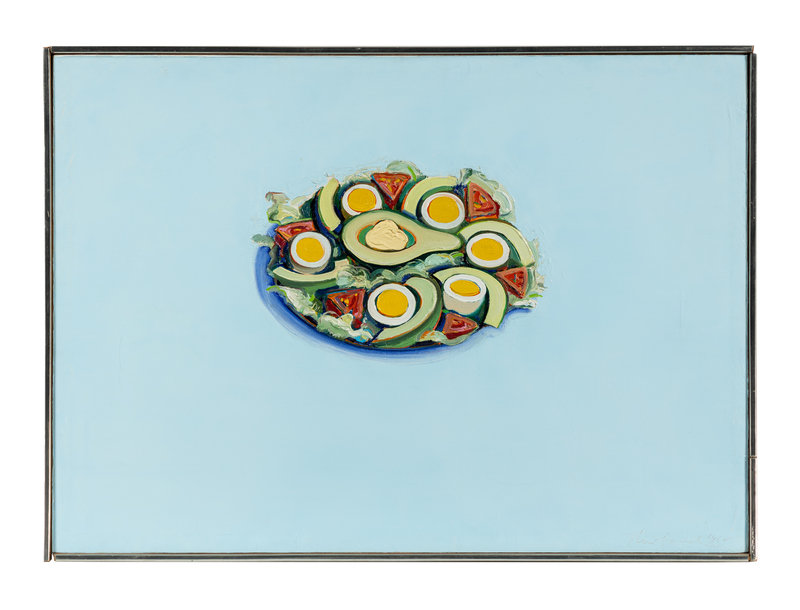

Though touching on a wide variety of quintessentially American subject matter throughout his career—landscapes and cityscapes of his local California, portraits, lipstick containers, and paint cans—most emblematic of the works by Wayne Thiebaud (1920-2021) are his still lifes of foodstuffs. Rows and rows of gleaming pies and cakes in diner cases, jewel-like gumballs, sumptuous taffy apples and ice creams, frozen on canvas right on the precipice of beginning to melt in the warm pastel light, Thiebaud was an expert at creating a vision of a food somehow more transcendent and temping than the real thing. Avocado Salad (1962) is no exception. Pulling from advertising and his lived experience, Thiebaud was able to create the contained, lush scene through highlighting a subject that, though a ubiquitous cultural presence today, was a relatively new phenomenon to his audience of white middle-class America at the time—the avocado.

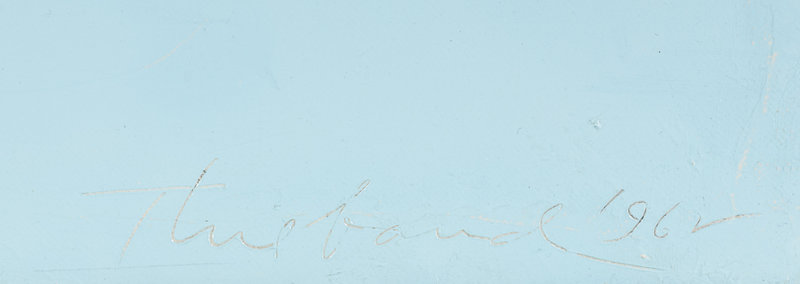

Born in Arizona in 1920, Thiebaud was long interested in the art of American popular culture, working for a stint in Disney’s Animation department at 16, as a layout designer and cartoonist based in adverting, and as an exhibit designer for the California State Fair and Exposition’s annual art exhibition in Sacramento, while also working on his own practice. He began work as a teaching artist in 1951, shifting from Sacramento Junior College (now Sacramento City College) to the University of California, Davis in 1960, from which he received a grant to travel to New York in the summer of 1961, where he would mix with local artists who would influence him greatly—Franz Kline, Jasper Johns, the de Koonings, among others— and also meet Allan Stone, his future gallerist who would become a life-long friend and champion for the artist’s work on the east coast, including through the use of the Museum of Modern Art’s Art Lending Service, as described below.

Based on his friendships with artists associated with the burgeoning Pop movement out east and his use of boldly colored quotidian objects plucked from mass culture, Thiebaud has often been defined as a Pop artist. However, scholars have rejected this identification based on the difference in Thiebaud’s goals and stylization. While Pop artists were known for seeking to deemphasize the artist’s hand in the work—more closely aping the coldly unemotional mechanized sameness of mass-produced imagery often pulled from advertising, Thiebaud, while still using some of the same source material, emphasized his presence and opinion wherever possible.[i] As noted by scholar and curator Scott A. Shields:

“While Warhol seems not to have liked soup, Thiebaud certainly enjoys his pie. This should not imply that Thiebaud’s paintings do not comment on consumerism and the isolation that one can feel even in an oversaturated world. They do. And yet, in their care and undeniable reverence for painting, they are also celebratory, validating art, the role of the artist, and the delicious idiosyncrasies of contemporary life.”[ii]

This joy and consideration is apparent in Avocado Salad where a bowl of judiciously arranged tomato and avocado slices and hard-boiled eggs encircle a halved avocado crowning interspersed lettuce leaves. The immediate impression of the uniform teal background dotted with vibrant circles of yellow yolks, bold red tomato slices, and pale green avocado gives way to a cornucopia of colors at closer inspection—delightful surprises of lush swathes of pink, blues, and oranges. Without blending these colors in space, they are juxtaposed in heavy impasto—an unavoidable announcement of the artist’s hand in the work— to form the harmonious whole. Thiebaud relies on strong geometries—only the wisps of lettuce offer organic shapes among the ovals and triangles and half-moons. Some of these forms are so abstracted that the viewer must rely on cultural cues to know what is being represented.

To the contemporary viewer, for whom the avocado is deeply entrenched in the Western cultural vocabulary—a symbol of indulgent, temporal experiences, of weekend brunches with Instagram-perfect plates of avocado-shingled toasts or a guacamole surcharge at a favorite Mexican spot—the avocado salad is an obvious choice. Yet, for Thiebaud, at the time of this composition, the avocado would have had a very different cultural role in America as an odder locality of California and the west coast.

The California avocado was a twentieth-century phenomenon: as California land speculation in the early 1900s took off, more and more growers would pounce on avocados as an economic opportunity.[iii] However, these growers were faced with a problem: how to sell middle-class America on the avocado—a rarely used fruit outside of Latin American cuisine. The California Avocado Society, formed in 1915, which would become Calavo in 1924, was a cooperative organization premised on marketing the avocado—and, very specifically, the California Avocado—to Americans.[iv] Calavo’s main tactic to introduce the fruit to the wider market was to bill it as a luxury—the “aristocrat of salad fruits,” while also downplaying its roots in ethnic culture through advertisements in women’s magazines and in recipe books, working to make it more palpable in the American mass culture of Thiebaud’s hot dogs and diner pies.[v]

However, for all their efforts, by the 1960s Calavo had mostly found success only in California and other parts of the west as a popular regional food, causing avocado growers to shift the marketing arm of Calavo to a new organization, the California Avocado Advisory Board, in 1961, injecting new money and energy into avocado marketing in the year before Thiebaud’s composition.[vi]

The images in these advertisements, of simple geometries colored in blocks of yellow and green or salad bowl ovals tilted forward to reveal their lush avocado-decked contents within, often oriented higher on the page than center so that text can be added beneath, ring familiar—to the twenty-first-century viewer— in Avocado Salad. However, lest the east coast public not feel quite the same way in their avocado enthusiasm, Allan Stone took advantage of a fascinating program: the Art Lending Service (ALS) by the Museum of Modern Art to market the painting.

Begun in 1957, ALS was a program working in cooperation with about 60 galleries that allowed members of the public—so long as they were also museum members—to rent works of art for two-to-three-month periods, with the option to buy, with the idea that actually allowing patrons to experience artworks on their walls would galvanize sales in a way denied by the more sterile gallery space. [vii] The program included works by artists like Alexander Calder and Joan Miró for prices now staggering. Allan Stone lent Avocado Salad shortly after it was painted. It was $35 for a two-month rental and $52 for three months, with a purchase price of $750 less rental fees already spent.

At such a steal during this period of Thiebaud’s early popularity in the 1960s, some might have dismissed Avocado Salad’s subject matter. But, in describing his selection of everyday sights in his paintings while citing other artists’ waffling in their choice of still life subject for fear of selecting the banal, Thiebaud explained:

“We are hesitant to make our own life special…set our still lifes aside…applaud or criticize what is especially us. We don’t want our still lifes to tattle on us. But some years from now our foodstuffs, our pots, our dress, and our ideas will be quite different. So if we sentimentalize or adopt a posture more polite than our own we are not having a real look at ourselves for what we are. My interest in painting is traditional and modest in its aim. I hope that it may allow us to see ourselves looking at ourselves.”[viii]

In his embrace of the then humble avocado, Thiebaud was able to show a fixture of his own lived experience in California in 1962, enhancing it from a spirited advertising campaign through bright colors and personalized abstraction with thick, sumptuous brushstrokes into a work dazzling for all.

------------

[i] Karen Wilken, “An American Master,” in Wayne Thiebaud, ed. Kenneth Baker (New York: Rizzoli, 2022), 13.

[ii]Scott A. Shields, “Bakery Counter, 1993” in Thiebaud: delicious metropolis, ed. Wayne Thiebaud (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2019), 37.

[iii] Jeffrey Charles, “Searching for Gold in Guacamole: California Growers Market the Avocado, 1910-1994,” in Food Nations: Selling Taste in Consumer Societies, eds. Warren Belasco and Philip Scranton. (New York: Routledge, 2002), 134.

[iv] Ibid., 140.

[v] Ibid., 141-142.

[vi] Ibid., 143; 146.

[vii] “Background Information on the Art Lending Service,” The Museum of Modern Art (Spring 1957), accessed August 24,2023, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/2171/releases/MOMA_1957_0029.pdf.

[viii] Wayne Thiebaud, “Artist Statement,” in Thiebaud: delicious metropolis, ed. Wayne Thiebaud (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2019), 8.

Bibliography:

“Background Information on the Art Lending Service.” The Museum of Modern Art (Spring 1957). Accessed August 24,2023.https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/2171/releases/MOMA_1957_0029.pdf.

Charles, Jeffrey. “Searching for Gold in Guacamole: California Growers Market the Avocado, 1910-1994.” In Food Nations: Selling Taste in Consumer Societies, edited by Warren Belasco and Philip Scranton, 131-154. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Shields, Scott A. “Bakery Counter, 1993.” In Thiebaud: delicious metropolis, edited by Wayne Thiebaud, 56-57. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2019.

Thiebaud, Wayne. “Artist Statement.” In Thiebaud: delicious metropolis, edited by Wayne Thiebaud, 8-9. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2019.

Wilken, Karen. “An American Master.” In Wayne Thiebaud, edited by Kenneth Baker, 10-19. New York: Rizzoli, 2022.