Lot Essay:

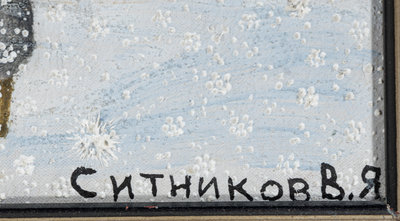

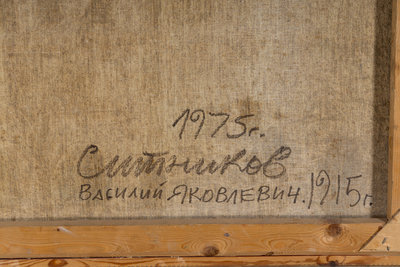

The theme of monasteries in snow would be one that Soviet Nonconformist artist Vassili Yakovlevich (Vasily) Sitnikov (1915-1987) would return to often and which proved to be particularly popular. This example, from 1974, with the masterly application of a limited color palette of whites, blues, and grays, with a judicious use of pale yellow and red, define the very Russian subject, with the monastery’s onion domes and scattered citizens in the foreground, including a knot of children, dressed in twentieth-century winter gear. The flat treatment of the scene, smoothing out the perspective of the monastery to less of a building and more of a wall, and, with the cut-out nature of the figures, lends the impression of a stage set, with the entirety of the scene obfuscated through the fastidiously and beautifully applied snowflake curtain.

The flatness and the scale of monastery to the inhabitants in the foreground thematically would have the potential of being imposing, a cold and unforgiving environment in the snow; yet, Sitnikov’s treatment actually relays the opposite through his comforting pale, cool, lustrous tones and the complete ease through which his inhabitants amble through the snow: a parent and child hand-in-hand, neighbors stopping for a chat. The monastery becomes an ideal—an atmospheric, traditional Russian environment peopled by Russians at peace. Sitnikov’s wistful treatment is perhaps not surprising given his tumultuous life and relation to the Soviet government.

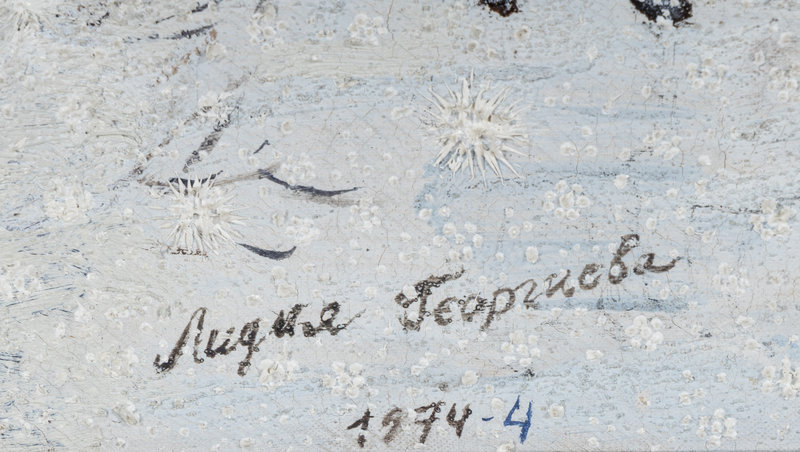

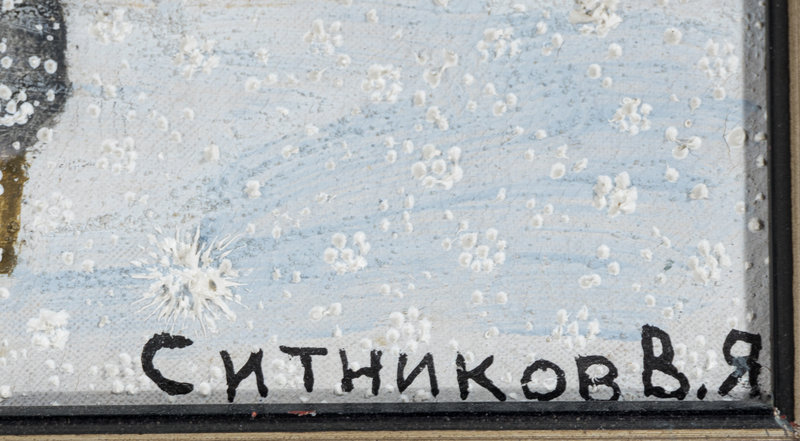

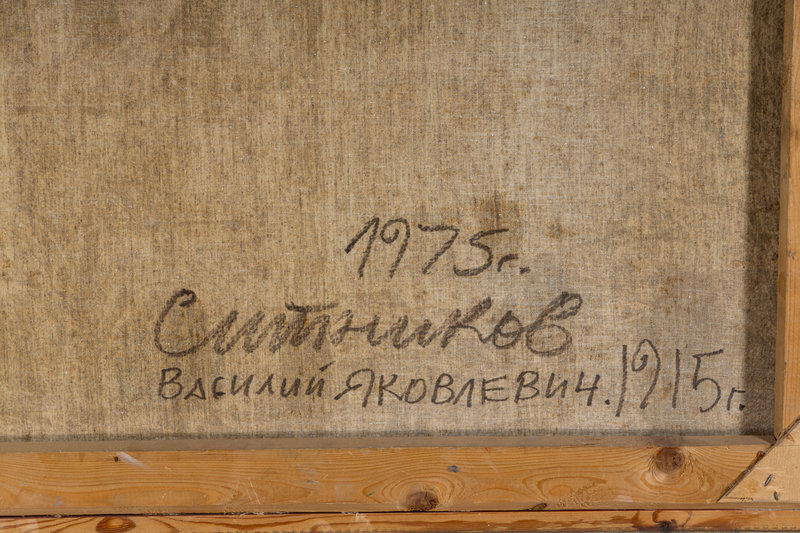

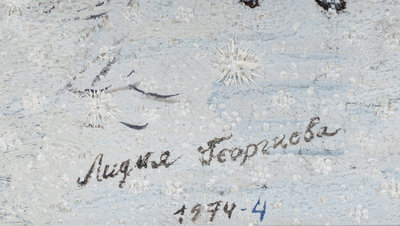

In 1934, Stalin defined his expectations for Soviet art, Social Realism—a propagandistic style extoling the virtues of humble Russians depicted in warm, glowing tones—of Stalin walking through a sun-drenched meadow, surrounded by adoring children. Meanwhile, modern, more avant-garde styles such as abstraction were suspect and increasingly criminal. Sitnikov was arrested in 1941 and was later institutionalized in a mental hospital. Later in his life, once released and, amid socio-political shifts like the Thaw that permitted a greater variety of artistic expression, Sitnikov fulfilled a life-long interest in teaching, while also propagating his style as well as his own personal mythology. His wife, Lidia Krokhina, was a student of his, and she also signed this painting as a collaborator. A year after this work’s completion, in 1975, Sitnikov would leave Russia for Austria for five years, before emigrating to the United States in 1980, living in New York for the remainder of his life. It is through such scenes as this that encapsulate his oeuvre—of the intersection of Russian tradition and modern painting.