Lot 40

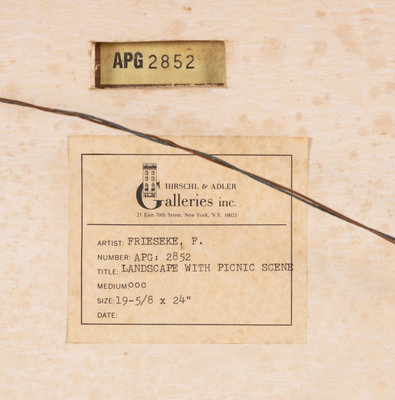

Paysage (Moret) is included in the draft Frieseke Catalogue Raisonne compiled by Nicholas Kilmer, the artist’s grandson, with the support of the Hollis Taggart Galleries. That draft is now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art. The work’s original title, Passage Moret, in what appears to be the artist’s hand, is inscribed on a damaged paper label verso.

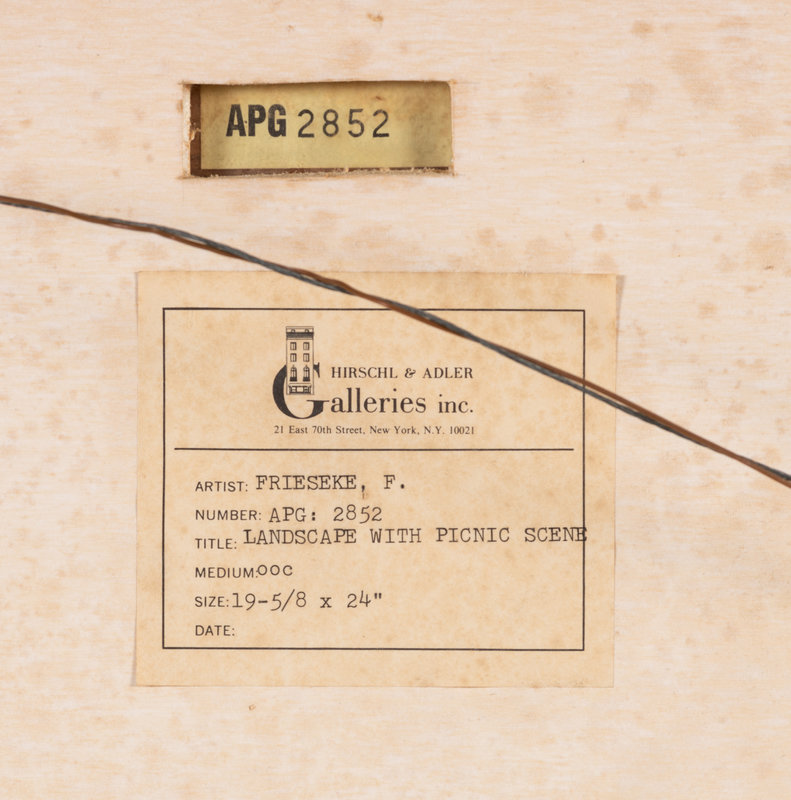

Provenance:

Private Collection, Washington, DC

Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, acquired from the above, April 1978 (as Landscape with Picnic Scene)

Acquired from the above by the present owners, October 1978

Exhibited:

Saginaw, Michigan, Saginaw Art Museum, Frederick Carl Frieseke: American Impressionist, September 11, 1983 - January 1, 1984 (as Landscape with Picnic Scene)

Lot note:

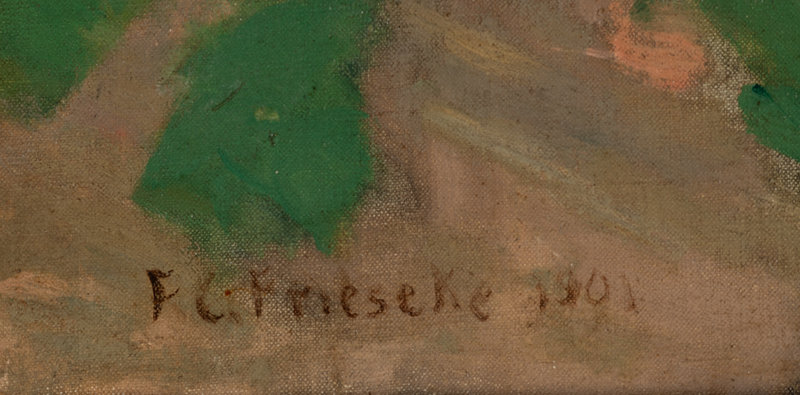

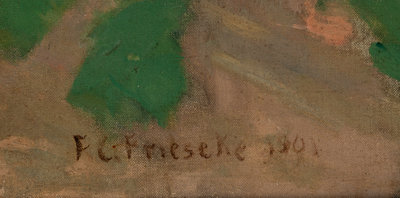

In 1901, Carl Frederick Frieseke wrote to Sadie O’Bryan, who would soon become his wife, that “landscape is by far the most difficult thing I have tackled” (see Frederick Carl Frieseke: The Evolution of an American Impressionist, Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 21). Until then, Frieseke had indeed mostly focused on nudes and his early manner aligned with the French academic tenets he learned at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the mid-1890s, and later at the Académie Julian in Paris, which he attended from 1897 until 1900. With the new century, however, Frieseke’s artistic horizon would broaden, thanks in large part to the teachings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler at the Académie Carmen, an art school in Paris targeting British and American students.

Whistler championed a very painterly aesthetic, bringing forth a style defined by the broad application of loose swaths of uniform tonalities, resulting in the suggestive arrangement of cursory forms, unconstrained by the strict delineation of drawing. The artist remained very much in control of the design, orchestrating a careful selection of natural details, while consciously omitting others. In her essay “Frieseke’s Art Before 1910,” H. Barbara Weinberg reminds us that Whistler’s ultimate advice to his students was to “judiciously [select] from nature rather than merely [transcribe] appearances” (see Frederick Carl Frieseke: The Evolution of an American Impressionist, p. 60). Weiner also identifies several other movements that may have influenced Frieseke at the turn of the century. Among them are the sinuous, curvilinear patterns of Art Nouveau, the attenuated and blurred contours of Pictorial photography, and the profuse, colorful, blending shapes and figures of the Nabis. According to Weiner, all evince the artifice in art, the fact that it is constructed, and underline the complex relationship artists and designers forged between their practice and the natural world around them.

In the summer of 1901, Frieseke is known to have spent time in Le Pouldu, a small village in Brittany near Pont-Aven, which was a major Impressionist art colony during the second half of the 19th century. Paysage is purported to be depicting Moret-sur-Loing, a village located southeast of Paris, and while such a visit is not documented, it may be that Frieseke visited the area on occasion, as it was a favorite locale of the previous generation of Impressionist painters, including Alfred Sisley and Gustave Loiseau. The present work splendidly augurs Frieseke’s forthcoming embrace of the landscape as a primordial artistic subject, displaying key Impressionist features such as a loosening, experimental brushwork, a thoughtful arrangement of details gleaned from nature, and a brilliant, colorful palette. Over the years, and especially after 1905, when he would visit Giverny every summer until 1919, Frieseke’s strand of Impressionism would evolve into a highly distinctive aesthetic, as he increasingly devoted himself to representing the outdoors, masterfully capturing the visual impact of sunlight on the landscape and the figures in it.