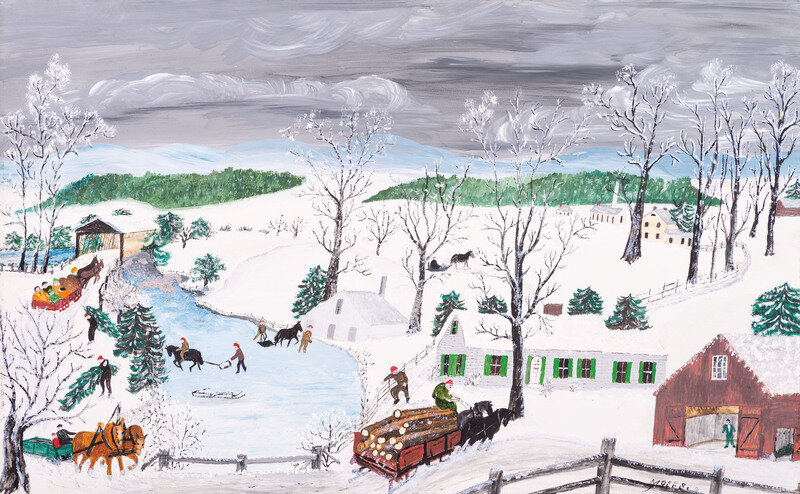

Lot 26

Grandma Moses

(American, 1860-1961)

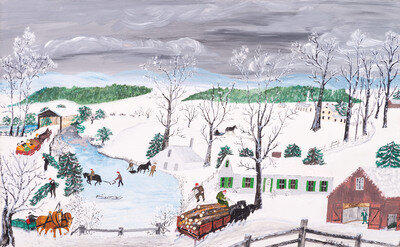

Cutting Ice, 1951

Sale 1339 - American Art

May 16, 2024

2:00PM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$50,000 -

70,000

Price Realized

$47,625

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Grandma Moses

(American, 1860-1961)

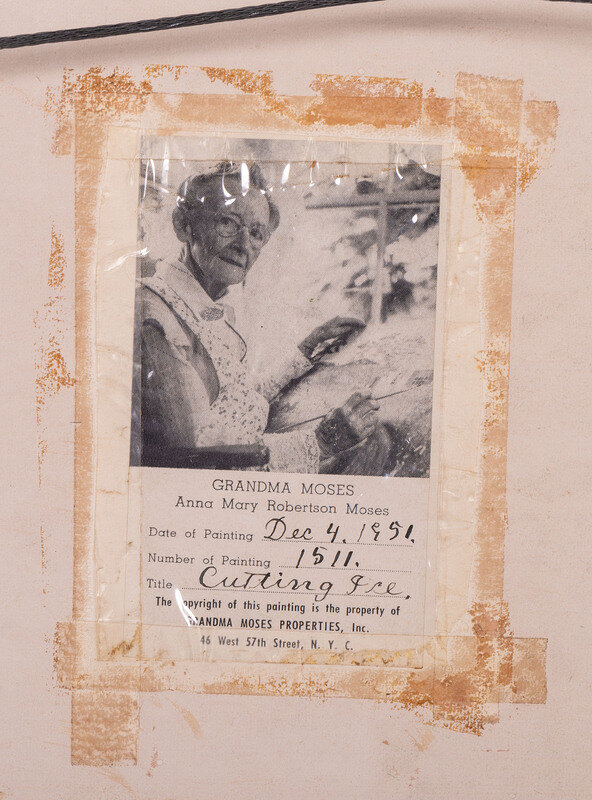

Cutting Ice, 1951

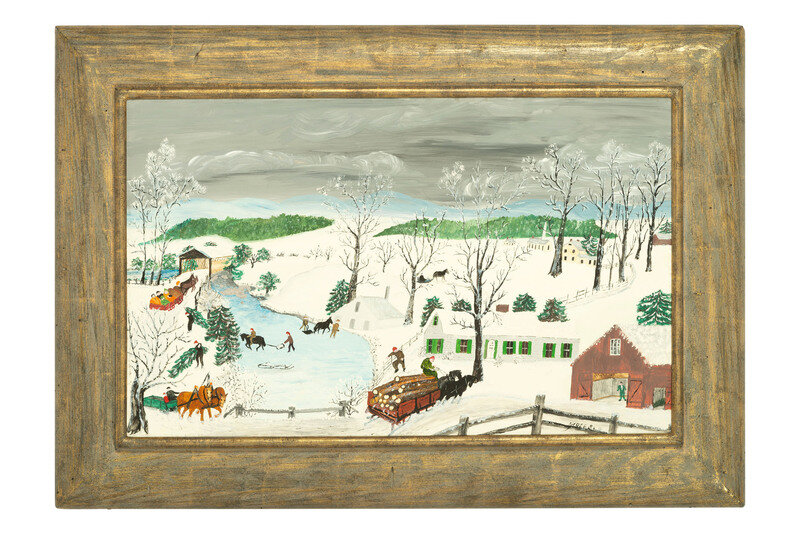

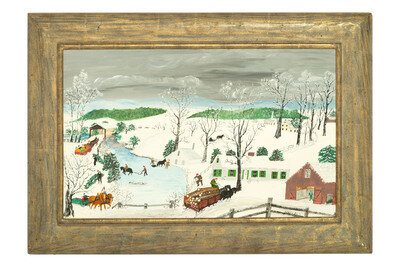

oil on masonite

signed Moses. © (lower right)

15 x 23 3/4 inches.

Property from the Estate of Paul G. Benedum, Jr., Ligonier, Pennsylvania

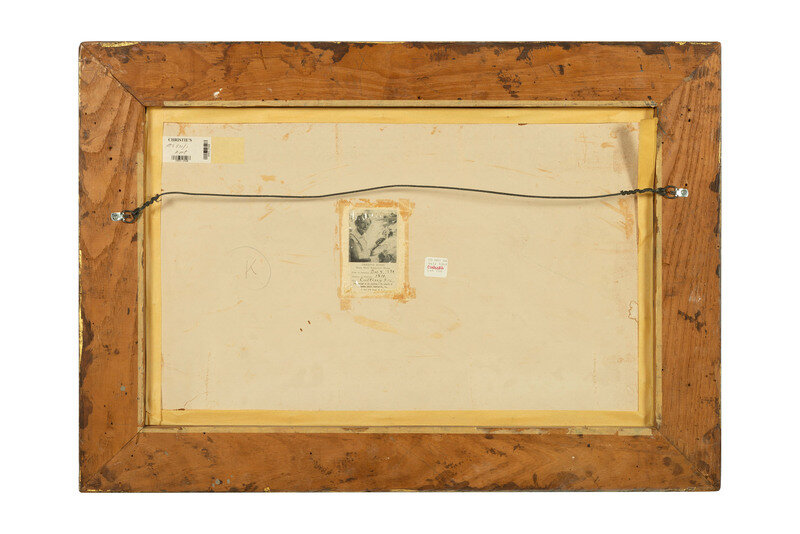

Provenance:

J.C. Anderson

Sold: Christie's, New York, May 25, 2000, Lot 152

Literature:

Otto Kallir, Grandma Moses, New York, 1973, no. 1020, p. 310, illus.

This work, executed on December 4, 1951, is no. 1511 in the artist's record book.

The copyright for this picture is reserved to Grandma Moses Properties, Co., Inc., New York.

Lot note:

The Old Oaken Bucket, 1944, and Cutting Ice, 1951, both present a remembrance of farm life in elaborate narrative detail. Although Anna Mary Robertson Moses, soon to be dubbed Grandma Moses, at first worked in relative obscurity, her art was discovered at a time when folk artists were garnering broader attention. Widowed in 1927, Moses lived on an upstate New York farm, when in the 1930s, she began to devote her spare time to painting. She gifted her artworks to family and friends and exhibited them at country fairs with her jams and preserves. She also showed her paintings in the window of a local drugstore. In the spring of 1938, these were noticed by the collector Louis Caldor, who subsequently captured the interest of Otto Kallir, owner of Galerie St. Etienne in New York. At the time, the gallery primarily exhibited Austrian Expressionists such as Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and Alfred Kubin. Kallir later remembered one painting in particular, "It was a sugaring-off scene...But what struck me...was the way the artist handled the landscape...Though she had never heard of any rules of perspective, Mrs. Moses had achieved an impression of depth [with color]...creating a compelling truth and closeness to nature." (Otto Kallir, Grandma Moses, New York, 1973, p. 35)

In October 1940, at age 80, Moses had her first exhibition in New York, What a Farm Wife Painted, at Galerie St. Etienne. Her paintings were seen by the critics as a refreshing respite to the reductive Modernist art of the day. One wrote, "When [Grandma Moses] paints something, you know right away what it is--you don't need to cock your head sideways like when you look at some modern dauber's effort..." (as quoted in J. Kallir, Grandma Moses in the 21st Century, Alexandria, Virginia, 2001, p. 23) It was at this debut show at Galerie St. Etienne that Moses was declared by a New York Daily Mirror writer to be "more than a great American artist. She's a great American housewife." The writer's comment underscores an important element of Moses’ art, which reflected cherished American family values and traditions. "Moses was proud of her women's work in general, aware that on the farm survival depended on a true division of labor between the sexes. As a girl she had learned the skills of female adulthood, and as a grown woman she practiced them with pride and proficiency." (Designs on the Heart: The Homemade Art of Grandma Moses, p. 136)

The present two artworks highlight Moses’ distinctive painting style, as well as her belief that men, women, and children all had a role in the community’s daily work, which in turn brought happiness to the farm. The activities are enhanced by her use of patterns composed of vibrantly colored blocks of shapes. Moses said she painted joy in her palette, "because I wanted other people to be happy and gay at the things I painted with bright colors." (as quoted in J.E. Stein, "The White-Haired Girl: A Feminist Reading," Grandma Moses in the 21st Century, p. 50) The artist also used texture to add depth, applying thick impasto to render tree blossoms and snow-covered branches, while smooth brushstrokes describe the background. Farm activity is concentrated in the foreground, with the serene landscapes giving way to expansive vistas and undulating mountains. Although Moses had no formal artistic training, she achieves depth by gradually reducing the size of the trees and figures. A reporter who met with Moses wrote in The New York Herald Tribune, "As Grandma Moses talked of the technique of painting, a curious look came over her face, and suddenly she was no longer a quaint figure nor [sic] a curiosity…In that swift glimpse the visitor could see that Grandma Moses, untaught, uneducated, with very little understanding of her own gifts, is a true artist." (as quoted in Grandma Moses: The Art Behind the Myth, p. 77)

As in all her best works, both The Old Oaken Bucket and Cutting Ice, Grandma Moses includes many details of rural community life. The title of The Old Oaken Bucket is derived from the song of the same name. In 1877, Moses worked for an elderly woman, Mrs. David Burch, who claimed that the well on her farm was the song’s inspiration. After Moses was awarded the New York State Prize for her first rendition of the theme, she received many requests for a duplicate of the work. Although she honored these requests and executed multiple variations, no two are the same. Moses found ways to vary the compositions, either by changing the season or varying the figures’ individual tasks. In the present The Old Oaken Bucket, a man gathers water from a well with the titular bucket; a child teases farm animals with a branch; a couple walks toward a bridge. Likewise, the artist made two versions of Cutting Ice, both in 1951. The first version, painted on July 5th, is in an oval format with fewer figures engaged in winter pastimes, while the present painting, painted on December 4th, is rectangular and full of activity. These two idyllic scenes manifest every element that makes Grandma Moses an American icon.

Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist