Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 5

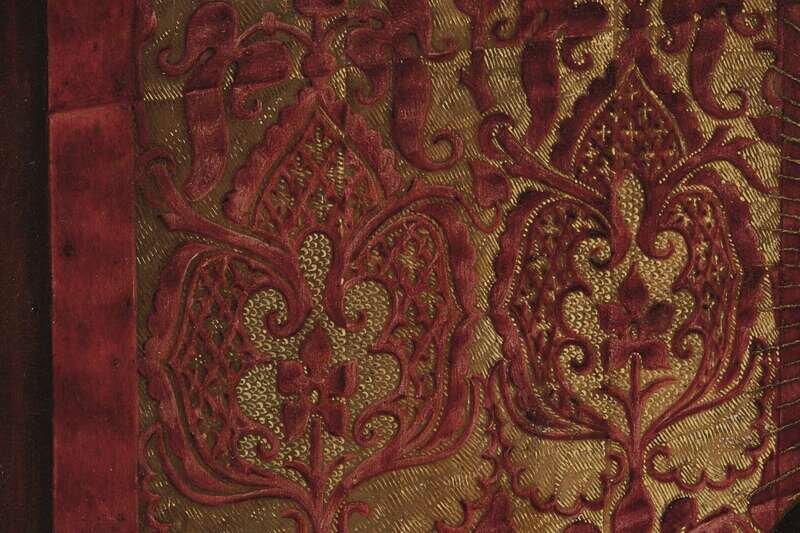

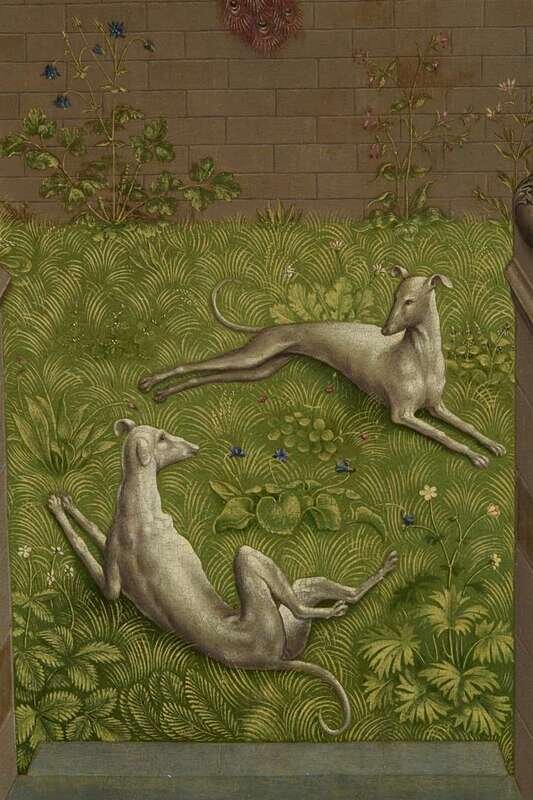

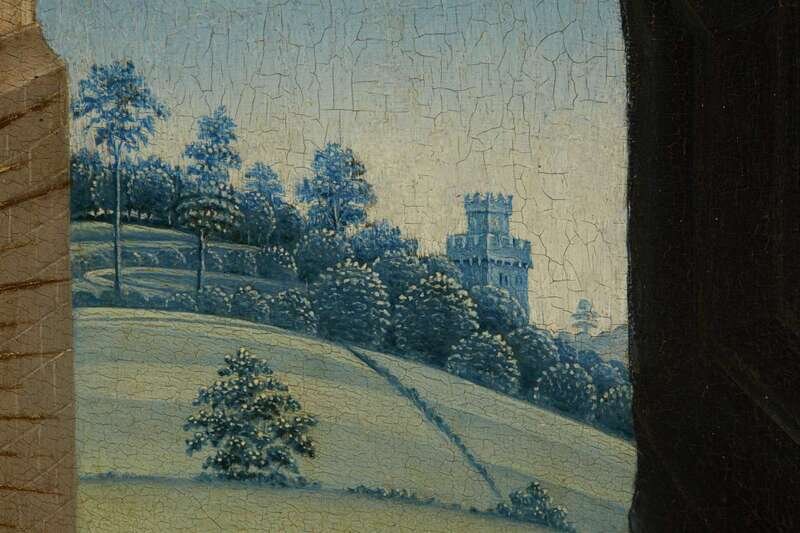

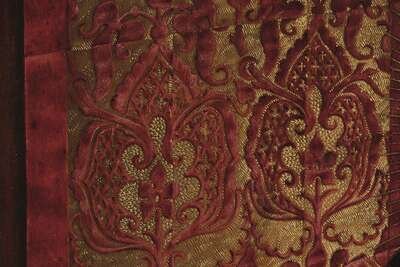

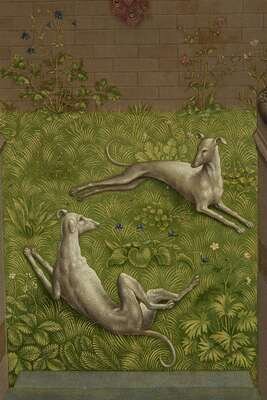

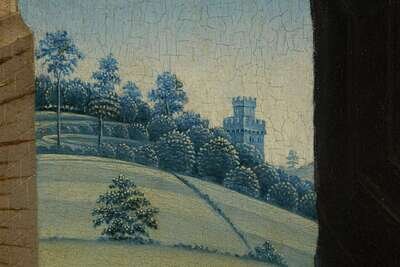

Master of the Embroidered Foliage (Netherlandish, active Brussels, late 15th Century) Nursing Madonna

Sale 5353 - European Art & Old Masters: 500 Years

Feb 27, 2019

7:00AM ET

Live / Philadelphia

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$150,000 -

250,000

Price Realized

$2,470,000

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Master of the Embroidered Foliage (Netherlandish, active Brussels, late 15th Century) Nursing Madonna