Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 1

Lot Description

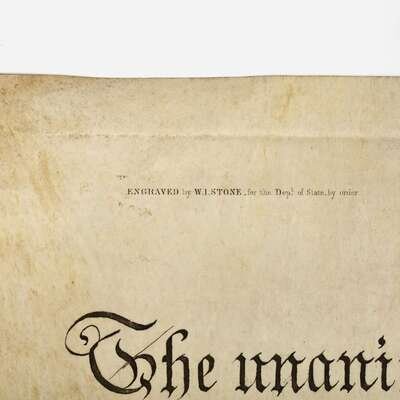

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.— That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…”

A remarkable find after 177 years: A long lost official William J. Stone copy of the Declaration of Independence presented in 1824 to signer Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

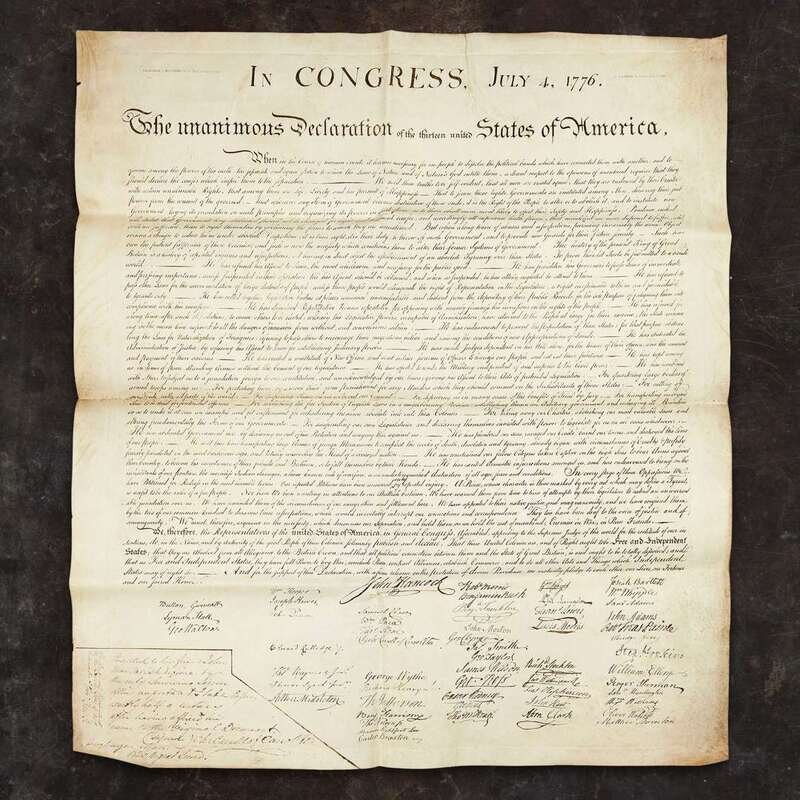

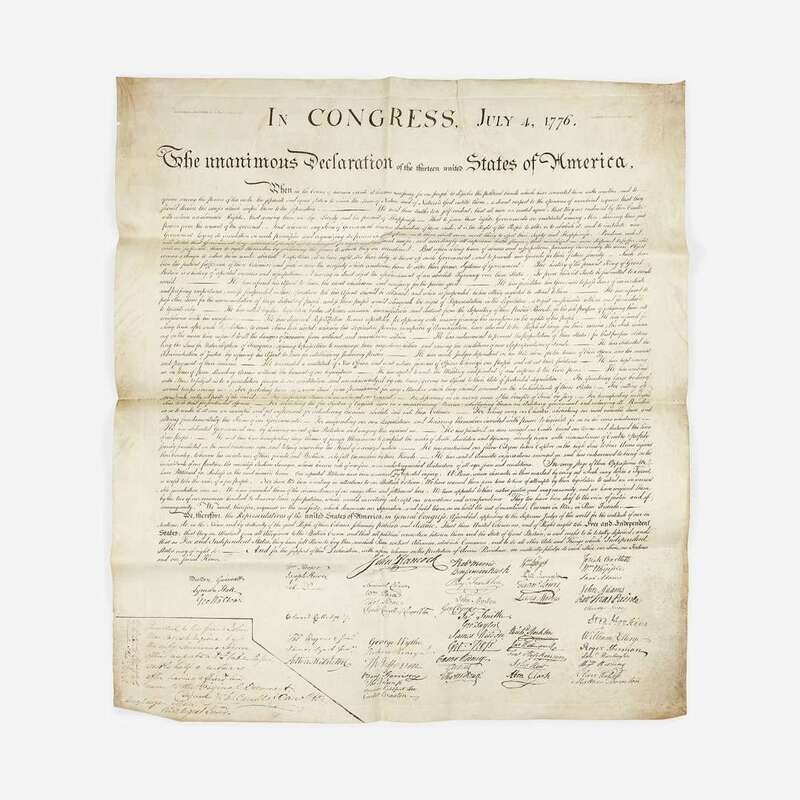

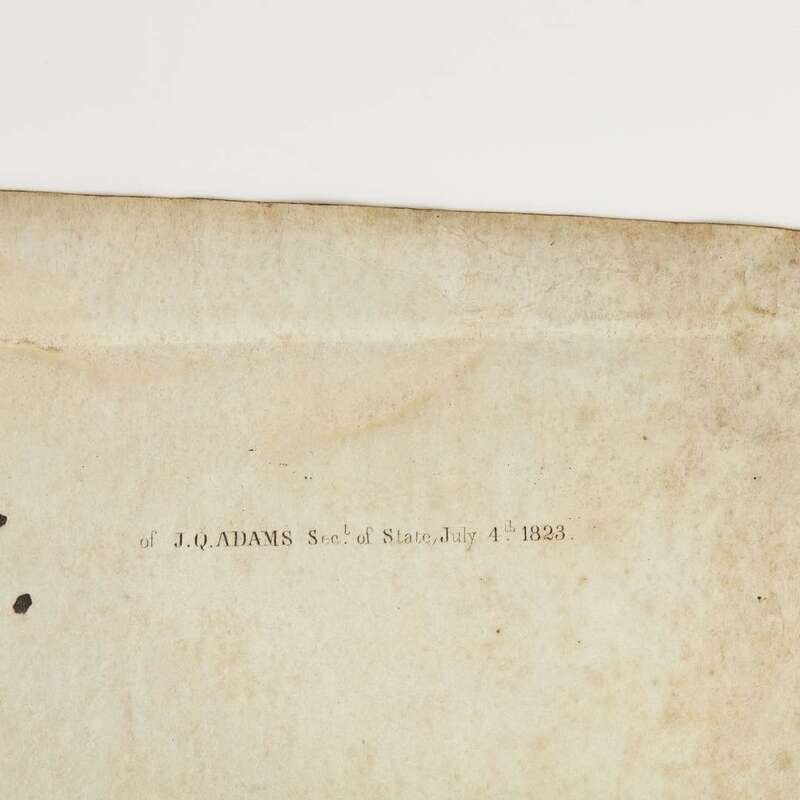

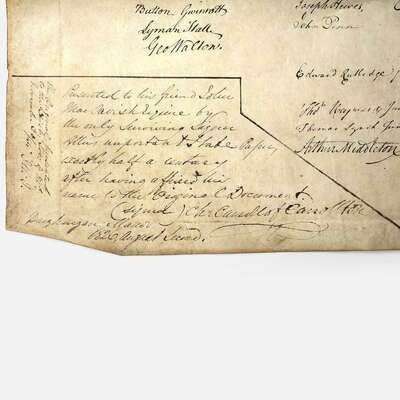

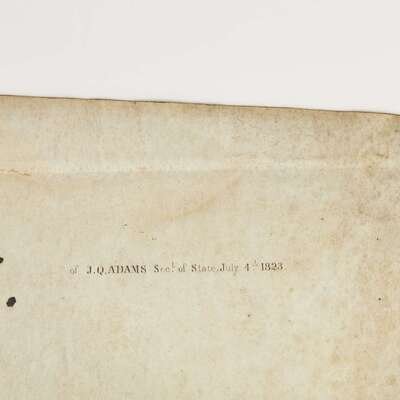

(Washington, D.C.): “ENGRAVED by W.I. STONE, for the Dept. of State by order/of J.Q. ADAMS Sect. of State, July 4th 1823”. Copperplate engraving on vellum.

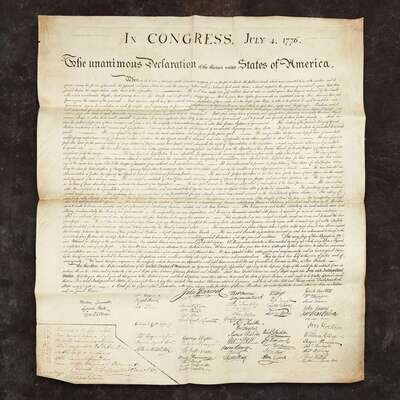

On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia resolved that the United States were “Free and Independent” from Great Britain. Two days later, the delegates approved the final text of what would later be referred to as the Declaration of Independence. It was then signed—only by John Hancock and Secretary of Congress Charles Thomson—then immediately sent to John Dunlap’s shop to print official broadsides (single printed pages with text only on one side). Over the next few days, Hancock sent Dunlap’s broadsides to the state governments, General George Washington, and other top commanders and political leaders. Congress waited for New York to change its abstention to yes then ordered the newly unanimous Declaration to be engrossed (written in a clear hand) onto parchment. Finished at the beginning of August, the signers added their signatures, mostly on August 2, 1776. Their names weren’t published until 1777.

In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, wanting to preserve for posterity the image of the original engrossed Declaration, obtained Congressional approval to commission William J. Stone to engrave a plate to make exact copies of the Declaration. After nearly three years, Stone completed his work.

In 1824, Congress ordered 200 copies printed for distribution. First on that list were two copies each to go to the three surviving signers: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton. Adams’ copies survive in the Massachusetts Historical Society, each with inscriptions that JQA added on the reverse when he was organizing his father’s estate. Jefferson’s estate was largely disbursed, and there is no record of where his Stone copies went; they are not counted among the signers’ examples known to survive.

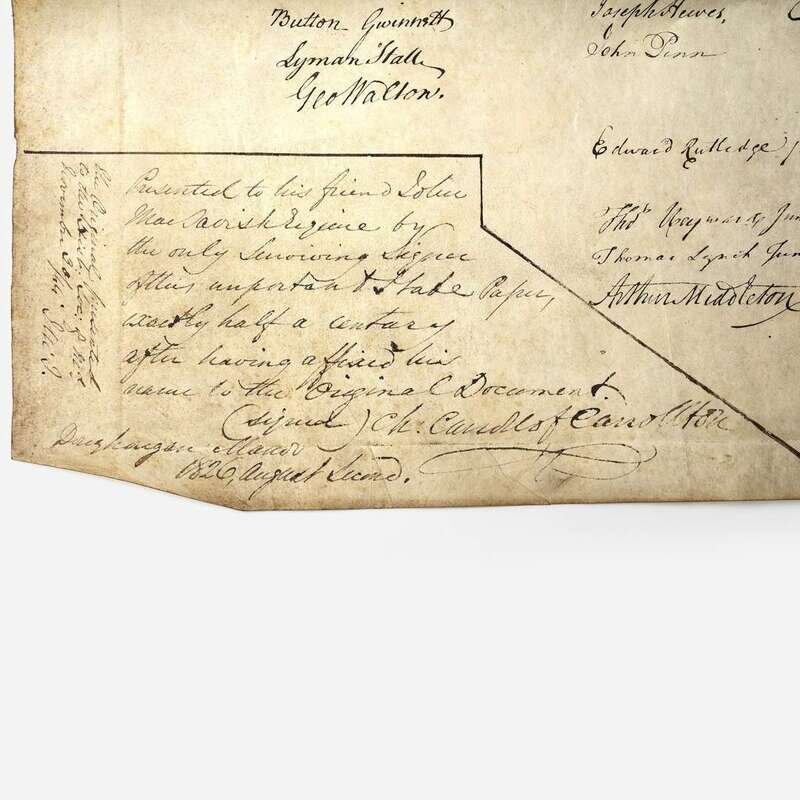

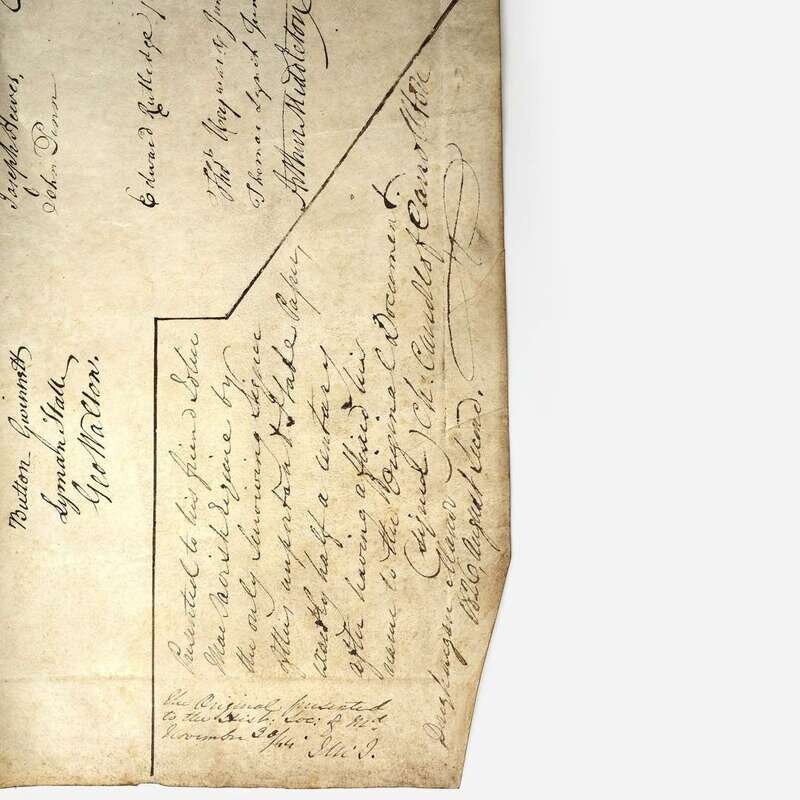

After July 4, 1826, when Adams and Jefferson died within hours of each other, Carroll became the last surviving signer of the Declaration, the one man with a living memory of the momentous decision. Four weeks later he inscribed and gave one of his copies to his grandson-in-law, John MacTavish. When the Maryland Historical Society was founded in 1844, MacTavish donated Carroll’s inscribed copy to them.

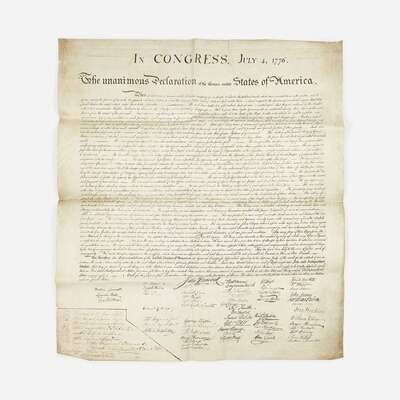

The inscriptions in the lower left corner of the example here tell the story of Carroll’s disposition of both of the copies he was given: "Presented to his friend John/Mac Tavish Esquire by/the only Surviving Signer/of this important State Paper,/exactly half a century/after having affixed his/name to the Original Document./(Signed) Ch. Carroll of Carrollton/ Doughoregan Manor/1826, August Second." The signer wrote that inscription on his other copy before giving it to MacTavish, who copied it onto this document (so Carroll’s “signature” here was penned by MacTavish), and then added: "The Original presented/to the Hist: Soc: of Md/November 30/[18]44./JMc T."

Condition

Original folds and light soiling. 31 3/4 x 27 3/8 in. (806 x 695 mm). A beautiful and strong impression, with very large margins.

Provenance

Presented to Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737-1832), 1824.

John MacTavish (1787-1852), husband of Carroll’s granddaughter, Emily Caton (1794/5-1867).

By descent in a Scottish family to present owner.

Note

The Declaration of Independence inspired the Revolution and provided a startling new vision for government, but was then shunted aside. The greatest breakup note and most monumental list of grievances in history actually made no attempt to establish a government to replace the system it was overthrowing. The Articles of Confederation was needed to do that, and the United States Constitution was needed to do it again, successfully.

Constant threat from powerful nations including Britain and France, and political battles that led to the first American parties, nearly ended America’s experiment in democracy many times in the first decades of its existence. Ironically, the War of 1812 disaster of the British invasion and burning of Washington, D.C. set the stage for a wave of patriotic reaction and reflection. The end of the War effectively confirmed America’s independence, and America’s founding document began to be transformed into a symbol at the core of America’s identity.

Entrepreneurs like John Binns and Benjamin Owen Tyler decided to capitalize on this new patriotic zeal by creating facsimile printings of the Declaration, including copies of the not yet famous signatures. As competition for the most faithful facsimile became heated, the need for an accurate version became apparent.

Secretary of State John Quincy Adams sought to preserve for generations to come not just the historic text, but what later became—in large part due to his prescient decision—the iconic look of the engrossed Declaration. (Adams might have been spurred on by the fact that Binns included portraits of John Hancock, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, but not his father John Adams, who was really the moving force behind adoption of the Declaration).

The engrossed Declaration, penned by Timothy Matlack and signed beginning on August 2, 1776, was already showing signs of deterioration. It had been carted around with the various moves of the government, rolled and unrolled to show to visitors, left unprotected from changes in temperature and humidity, and then used to model the first facsimiles.

In 1820, Adams commissioned master engraver and printer William J. Stone to create an exact facsimile of the Declaration. Using the original engrossed document, it took Stone about three years to completely engrave his copperplate. It had been assumed that to create a perfect facsimile, Stone employed some kind of wet or chemical ink-transfer process, but research by Seth Kaller, Inc. and by Harvard University’s Declaration Resources Project revealed evidence arguing against that, including several points where the Stone and the engrossed original differ. In any case, most of the severe damage that left the document almost entirely unreadable came later, caused by decades of display in direct sunlight and disastrous restoration efforts.

On May 26, 1824, through a joint resolution of Congress, Secretary Adams was instructed to distribute copies to various dignitaries and institutions. The last three surviving signers—John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Carroll—each received two copies, sent by JQA with cover letters dated June 24, 1824. John Adams' two copies now reside in the Massachusetts Historical Society. According to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson's two Stone copies, along with other facsimiles and prints relating to the Declaration, "were dispersed among his family following his death in 1826, and none are known to survive today." The President, Vice President, Congress, the Supreme Court, the White House, various governors and legislatures of the states and territories, each department of the Federal government, universities (fewer than 40 existed in the United States by then), and the Marquis de Lafayette, all received copies. Though they were not on Congress’s official distribution list, at least a couple of families of deceased signers received copies from allocated recipients.

On August 2, 1826, Charles Carroll, inscribed and gave one of his two copies to his grandson-in-law, John MacTavish, husband of Carroll's granddaughter, Emily Caton. That copy was then gifted by them to the fledgling Maryland Historical Society (now the Maryland Center for History and Culture) by the end of 1844.

Very few of the Stone Declarations have any evidence tying them to their original recipients. Were it not for the inscription by MacTavish and his copying here Carroll’s inscription on the donated copy the connection would have been lost. The present copy has been unaccounted for over the past 177 years.

Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737-1832) was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was a delegate to the Continental and Confederation Congresses, and later served as the first United States Senator from Maryland (1789-92), as well as in the Maryland State Senate (1781-1800). He was known as the "First Citizen" of the colonies due to his early support for independence, including influential articles he wrote under that name for publication in the Maryland Gazette.

At the time of the Revolution, Carroll was reportedly the wealthiest man in America, owning thousands of acres. After the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both on July 4, 1826, he became the last living signer of the Declaration.

John MacTavish (1787-1852) was a Scottish-Canadian diplomat and businessman who served as British Consul to the State of Maryland, and was also the heir to the Canadian North West Company fur trading business. He married Charles Carroll's granddaughter, Emily Caton (1794/5-1867), at Carroll's estate, Doughoregan Manor, on August 15, 1815. As a wedding gift, Carroll gifted them Folly Quarter farm, on nearby land. During the final years of Carroll's life, he was cared for by Emily in her downtown Baltimore home. In 1834, after the death of executor Robert Oliver, she was appointed executrix of Carroll’s estate by the courts. Emily's mother, Mary Caton, inherited Doughoregan Manor. When she died in 1846, it passed to Emily and her three sisters.

Catholicism and Civil Rights in America

In colonial and early Federal America, Catholics were deprived of religious freedom and civil rights in numerous ways: excluded from voting and holding public office, forbidden to have their own churches and schools, and subject to many other legal disabilities.

In Virginia, a 1641 law decreed that Catholics would be fined 1,000 pounds of tobacco for trying to hold public office. The next year, all Catholic priests were given five days to leave the colony. In 1661, the colony’s citizens were required to attend established Protestant services or face fines. In 1699, Catholics were deprived of voting rights, and in 1705, they were declared incompetent as witnesses in court. Anti-Catholic test oaths were required of all Virginia civil and military officers; George Washington would not have been granted his first military commission had he not signed one on March 19, 1754. (Test oaths were the result of an act requiring civil and military officials to deny key aspects of the Catholic faith, particularly the idea of transubstantiation.) He would soon find himself at the center of a battle that ignited war between Britain and France, a defeat that led him to sign the only surrender of his career. Ironically, his defeat there provided the experience needed to later shepherd America through the Revolutionary War, and his signature on the anti-Catholic oath undoubtedly provided some of his later motivation to expand rather than restrict religious freedom.

Most American Catholics, regardless of their treatment, favored the American Revolution. While Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Catholic among the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence, there were two among the 39 signers of the Constitution: Daniel Carroll of Maryland and Thomas Fitzsimons of Pennsylvania.

In March of 1790, President George Washington responded to a letter from the American Catholic community. Bishop John Carroll, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Daniel Carroll, Thomas Fitzsimons, and Dominick Lynch, had written to Washington encouraging respect for religion and furthering the ideal of religious liberty. (America’s foundational principal of religious freedom would soon be enshrined in the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791). Washington’s response validated their optimism and defined his understanding of equal treatment under the law:

“As mankind become more liberal they will be more apt to allow, that all those who conduct themselves as worthy members of the Community are equally entitled to the protection of civil Government. I hope ever to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality. And I presume that your fellow-citizens will not forget the patriotic part which you took in the accomplishment of their Revolution, and the establishment of their Government: or the important assistance which they received from a nation in which the Roman Catholic faith is professed.”

History teaches us to look forward fortified by knowledge gained from a foundational document such as this with all of its attendant threads. It also reminds us how fragile the beginnings of America really were.

This is a unique opportunity to own the only known copy of the Declaration of Independence, printed by William Stone on order of Congress, presented to a signer of the original document, still in private hands.

Freeman’s would like to thank Seth Kaller for his assistance with the authentication and cataloguing of this extraordinary historic document.