Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 13

Lot Description

During one of the most difficult years of his postwar life, General Nathanael Greene drafts a lengthy personal letter to George Washington

"After the war I was in hopes of repose but fortune will not allow me what I most wish for."

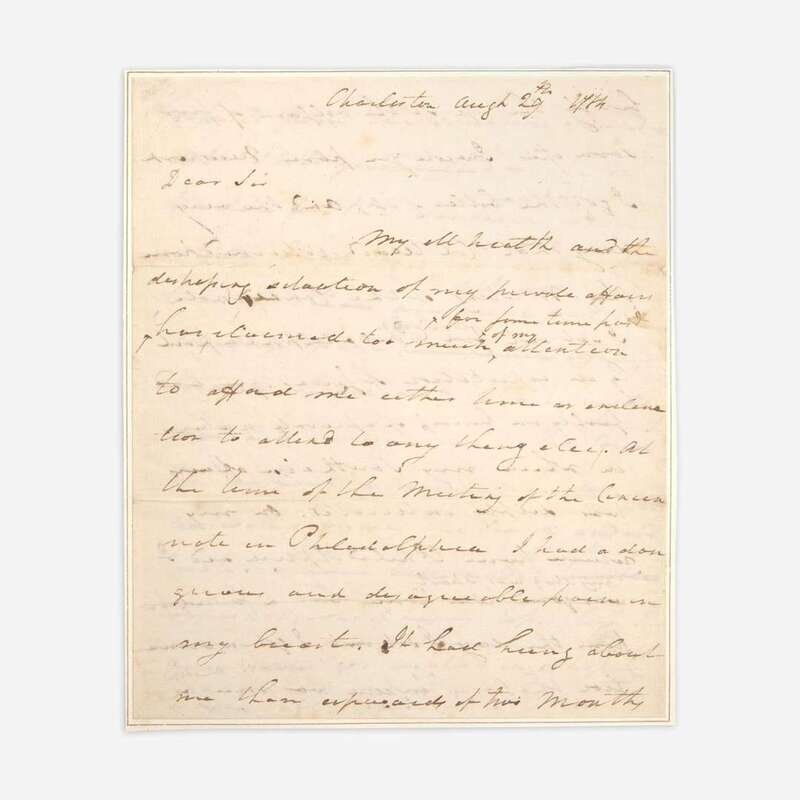

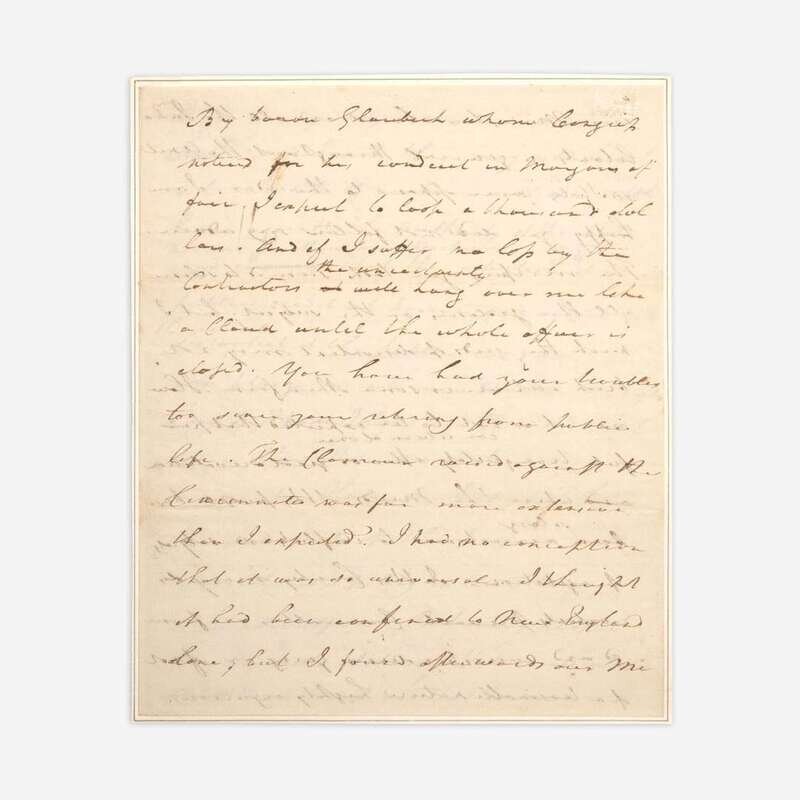

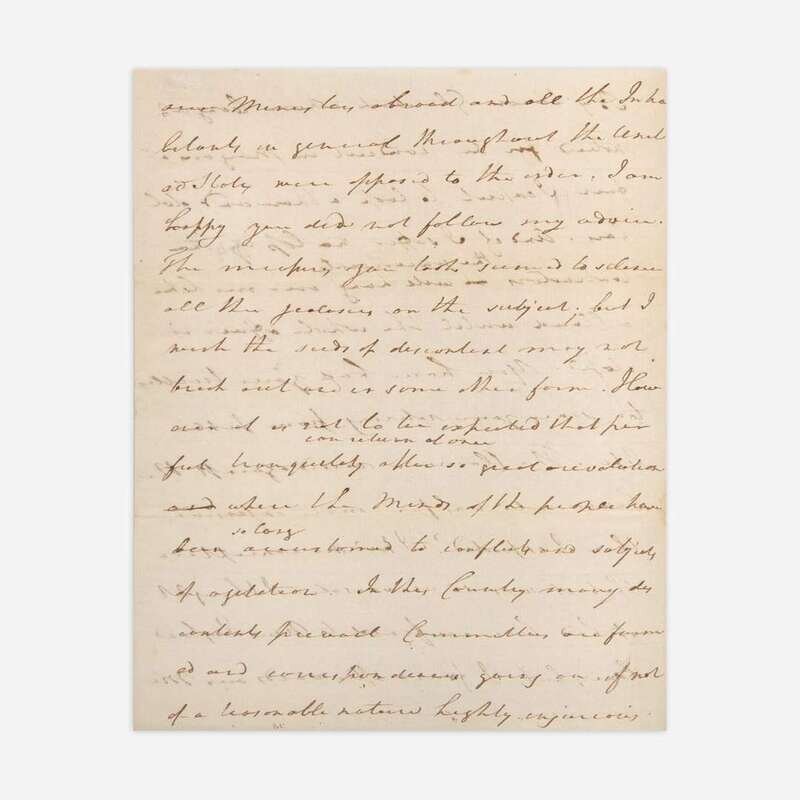

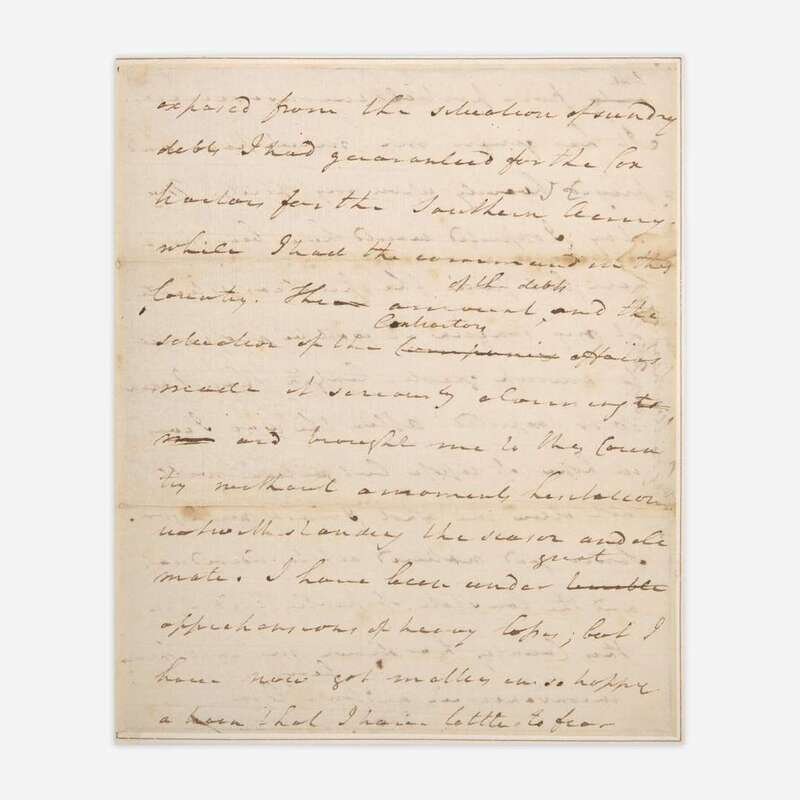

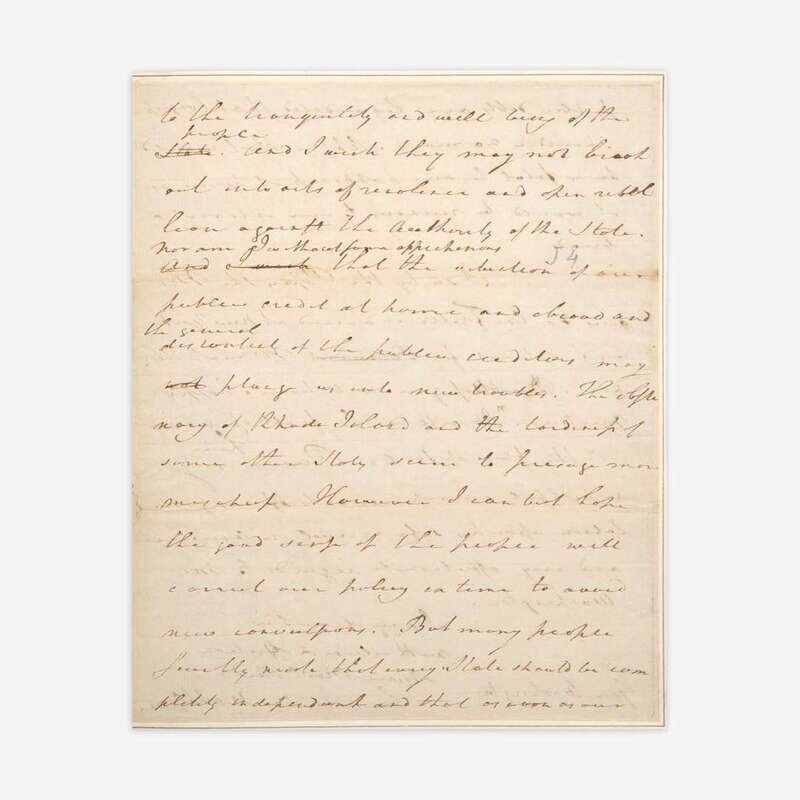

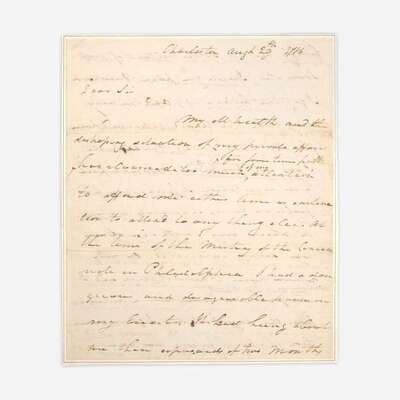

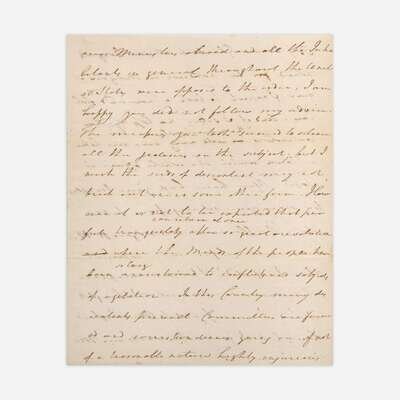

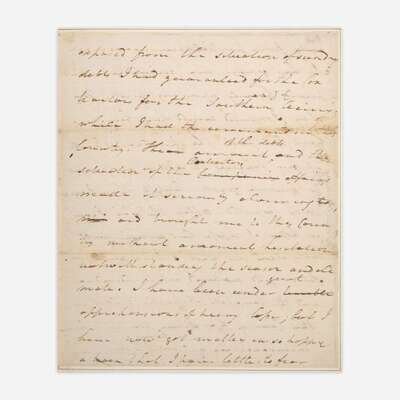

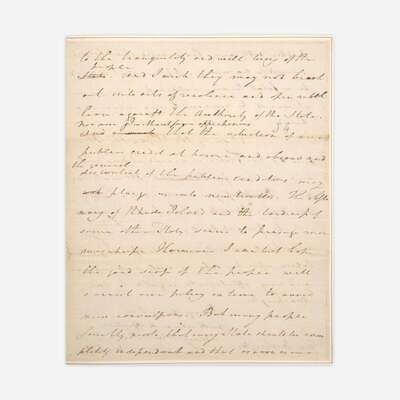

Charleston, (South Carolina), Aug(ust) 29, 1784. Two sheets, each folded to make four pages, each page measuring 9 x 7 1/4 in. (229 x 184 mm). Lengthy eight-page autograph draft letter, signed by Continental Army Major General Nathanael Greene, to General George Washington, concerning Greene's poor postwar finances and the general woes facing the young nation. Inlaid; creasing from contemporary folds; some scattered light soiling; in full green niger chemise. The finished version of this letter is held at the Library of Congress in the George Washington Papers, and is reprinted in The Papers of George Washington (Confederation Series, Vol. 2, 18 July 1784?–?18 May 1785, ed. W.W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992, pp. 59–61). A letterbook copy of this letter is held in the Greene Papers at the Huntington Library, California. Lot includes an engraved image of Greene.

"Dear Sir

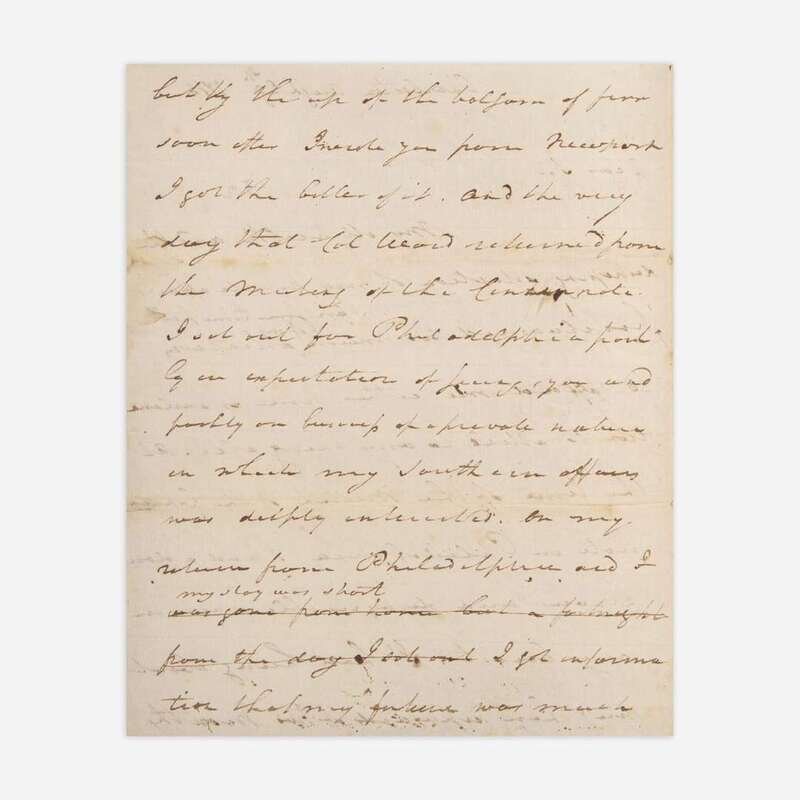

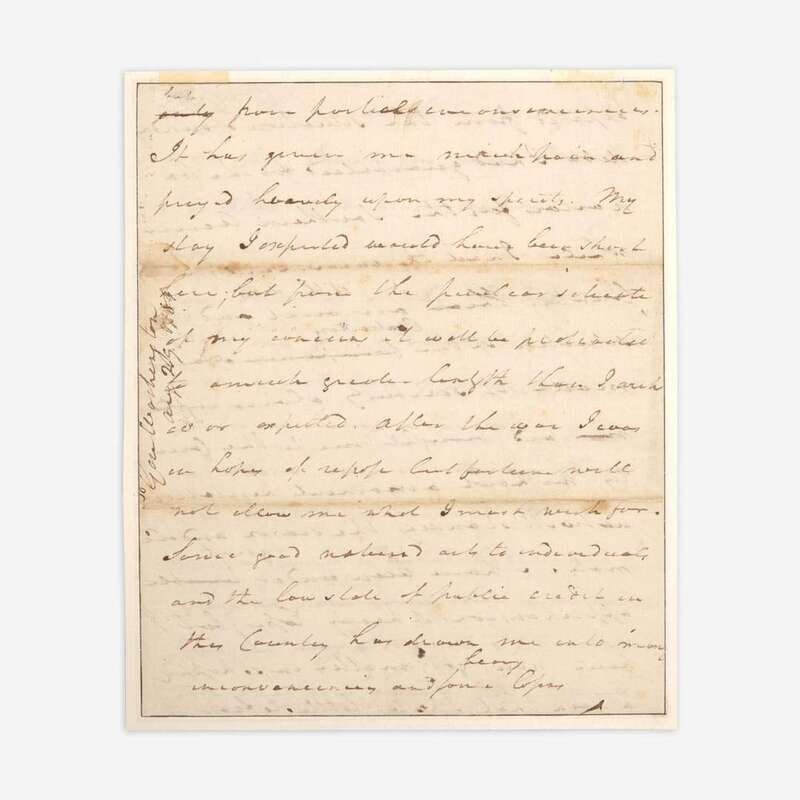

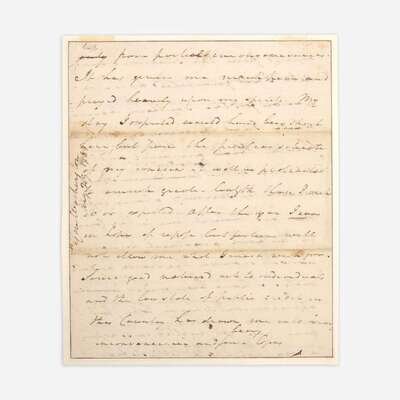

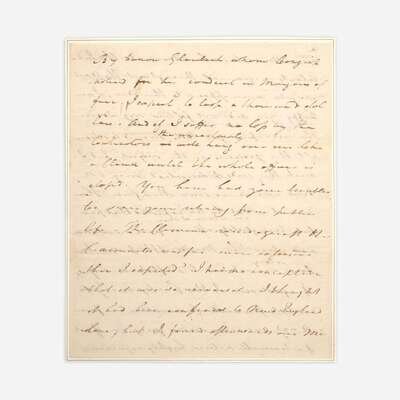

My ill health and the distressing situation of my private affairs for some time past have claimed too much of my attention to afford me either time or inclination to attend to any thing else. At the time of the Meeting of the Cincinnati in Philadelphia I had a dangerous and disagreeable pain in my breast. It had hung about me then upwards of two Months but by the use of the balsam of firr soon after I wrote you from Newport I got the better of it. And the very day that Col. Ward returned from the Meeting of the Cincinnati I set out for Philadelphia partly on expectation of leaving you and partly on business of a private nature in which my Southern affairs was deeply interested. On my return from Philadelphia and I was gone from home but a fortnight from the day I set out my stay was short I got information that my fortune was much exposed from the situation of sundry debts I had guaranteed for the Contractors for the Southern Army while I had the command in this Country. The amount * of the debts and the situation of the Companies Contractors affairs made it seriously alarming to me and brought me to this Country without a moment's hesitation notwithstanding the season and climate. I have been under terrible great apprehensions of heavy losses; but I have now got matters on so happy a train that I have little to fear only from partial inconveniences. It has given me much pain and preyed heavily upon my spirits. My stay I expected would have been short here; but from the peculiar situation of my concerns it will be protracted to much greater length than I wished or expected. After the war I was in hopes of repose but fortune will not allow me what I most wish for. Some good natured acts to individuals and the low state of public credit in this Country has drawn me into many inconveniences and some heavy losses.

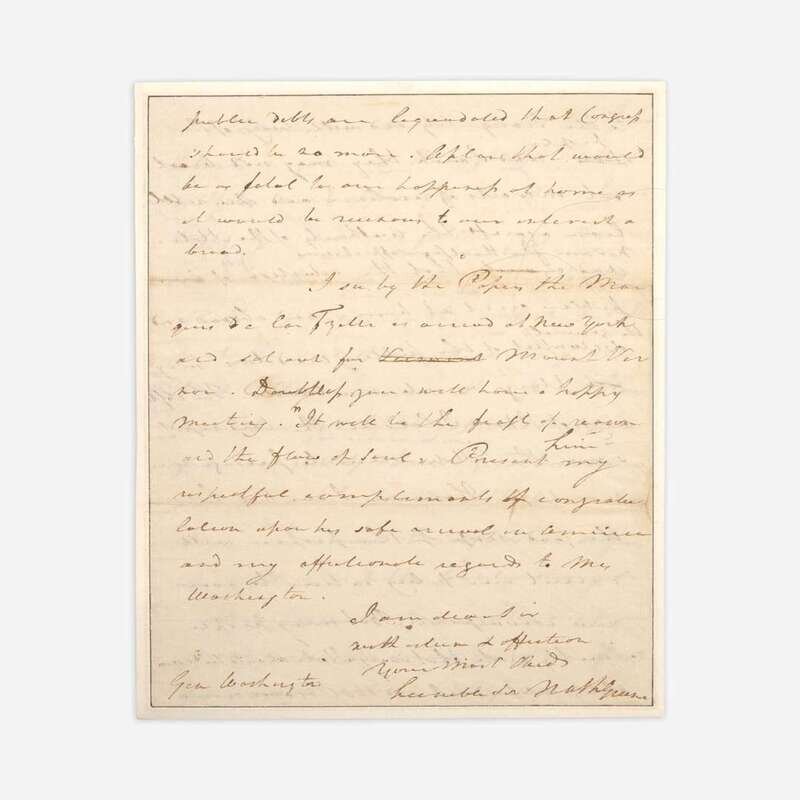

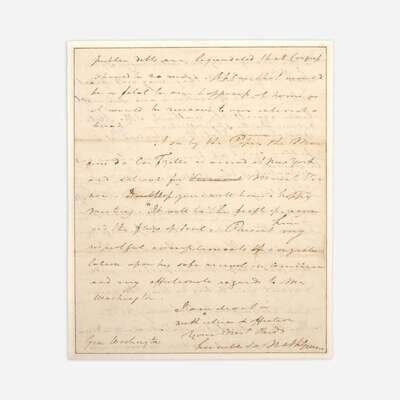

By baron Glaubert whom Congress noticed for his conduct in Morgans affair, I expect to loose (sic) a thousand dollars. And if I suffer no loss by the Contractors at the uncertainty will hang over me like a Cloud until the whole affair is closed. You have had your troubles too since your retiring from public life. The Clamour raised against the Cincinnati was far more extensive than I expected. I had no conception that it was so universal. I thought it had been confined to New England alone, but I found afterwards our Ministers abroad and all the Inhabitants in general throughout the United States were opposed to the order. I am happy you did not follow my advice. The measures you took seemed to silence all the jealousies on the subject; but I wish the seeds of discontent may not break out and in some other form. However it is not to be expected that perfect tranquility can return at once after so great a revolution and where the minds of the people have been so long accustomed to conflict and subjects of agitation. In this Country many discontents prevail Committees are formed and correspondences going on if not of a trasonable (sic) nature highly injurious to the tranquility and well being of the State people. And I wish they may not break out into acts of violence and open rebellion against the Authority of the State. And I wish Nor am I without some apprehensions that the valuation of our public credit at home and abroad and the general discontent of the public creditors may not plunge us into new troubles. The obstinancy of Rhode Island and the tardiness of some other States seem to presage more mischief. However I can hope the good sense of the people will correct our policy in time to avoid new convulsions. But many people secretly wish that every State should be completely independent and that as soon as our public debts are liquidated that Congress should be no more, a plan that would be as fatal to our happiness at home as it would be ruinous to our interest abroad.

I see by the Papers the Marquis de la Fayette is arrived at New York and set out for Vernon Mount Vernon. Doubtless you will have a happy meeting. "It will be the feast of reason and the flow of soul" Present him my respectful compliments of congratulations upon his safe arrival in America, and my affectionate regards to Mrs Washington.

I am dear Sir with esteem & affection your most obed. humble Ser. Nath Greene

Gen. Washington"

During one of the most challenging periods of his postwar life, Major General Nathanael Greene drafts a lengthy letter to his friend, former commander, and future first president, George Washington. Greene wrote this letter while in Charleston, South Carolina, shortly after returning from a visit to Philadelphia and Newport, Rhode Island, where he attended to his many creditors, and met with Congress in a failed attempt to settle his wartime debts. He recounts to Washington distressing news concerning the state of an injury he suffered that previous winter, his poor finances that have "preyed heavily upon (his) spirits," and offers his thoughts on the recent public backlash against the establishment of the Society of the Cincinnati. Greene finishes with a somber view on the general state of the young nation as it adjusted to independence, and cautions Washington of the many "discontents" that seek to undermine its future.

By the end of the Revolution General Greene was in financial ruin. After years of pledging much of his own fortune to support his army's needs, he entered private life nearly bankrupt, with large debts and bad credit. During his command of the Southern Army Greene guaranteed thousands of dollars in bills of credit in his own name in order to feed and clothe his army, which he became responsible for after the war due to a bankrupt Congress that could not reimburse him. Following the war his finances continued to decline after he made several "good natured acts to individuals," that often came in the form of loaning large sums of money to fellow Army officers who were similarly struggling with large war debts, and for which he was often never repaid. Although Greene wished for a peaceful postwar life with his family on his Georgia farm, his financial troubles consumed him and left him with neither "time or inclination to attend to any thing else." The year 1784 was particularly difficult for Greene. Injured from a fall in the winter of 1783 that left him in chronic pain for most of the following year, he learned in January that a hurricane destroyed his lucrative crops on his rice plantation in South Carolina. He spent much of the remainder of the year crisscrossing the east coast in an attempt to answer his numerous creditors who began calling in his debts. Adding to these economic pressures, he learned that summer the alarming news that he had become responsible for the debts of an unscrupulous South Carolina trader, John Banks, whom Greene utilized during the war to supply his troops.

Like Greene, the young nation faced an uncertain future after the Revolution, as it struggled with high war debts and a dim financial outlook. The Confederation Congress was weak against a fractious group of largely independent and powerful states, and throughout the 1780s it struggled to pass legislation for levying and collecting taxes as well as regulating trade that could improve the nation's economic situation. Both Greene and Washington understood Congress's weaknesses and the stubbornness of the states all too well, as they had each struggled against them during the war when trying to supply their armies. As the war receded into the past, a feeling predominated the country, and that Greene succinctly summarized to Washington, writing that "many people secretly wish that every State should be completely independent and that as soon as our public debts are liquidated that Congress should be no more." This sentiment was matched by a public suspicion of anything resembling British or aristocratic institutions. The establishment of the the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternal Continental Army club and mutual aid organization, fell victim to this feeling. Controversy quickly arose over the Society's hereditary membership and led to accusations that it intended to form a military aristocracy. In another letter written to Washington, Greene advised him not to yield to public outcry, but Washington attempted to make adjustments to the Society to ease public distrust. Greene was invited to attend the Society's first general meeting in Philadelphia the previous May (mentioned in this letter), but he was unable due to his injury.

As the nation's economic problems continued to grow after the Revolution, Greene and Washington both concurred about the need for a stronger national government to tackle them. Without one, as Greene prophetically warns here, the nation was in danger of unravelling into violence, writing that "In this Country many discontents prevail Committees are formed and correspondences going on if not of a trasonable (sic) nature highly injurious to the tranquility and well being of the people. And I wish they may not break out into acts of violence and open rebellion against the Authority of the State. Nor am I without some apprehensions that the valuation of our public credit at home and abroad and the general discontent of the public creditors may plunge us into new troubles." Nonetheless, Greene finishes with a glimmer of hope that a change can be made, "I can hope the good sense of the people will correct our policy in time to avoid new convulsions." Greene's hope came to fruition in the summer of 1787 with the convening of the Constitutional Convention. Greene, however, would not live to see either the ratification of the Constitution or the election of Washington as first President of the new federal government, as he passed away suddenly less than two years following this draft, in June 1786.

A fine example of this oft-quoted and important letter between two of the Revolutions most celebrated officers.