Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 21

Lot Description

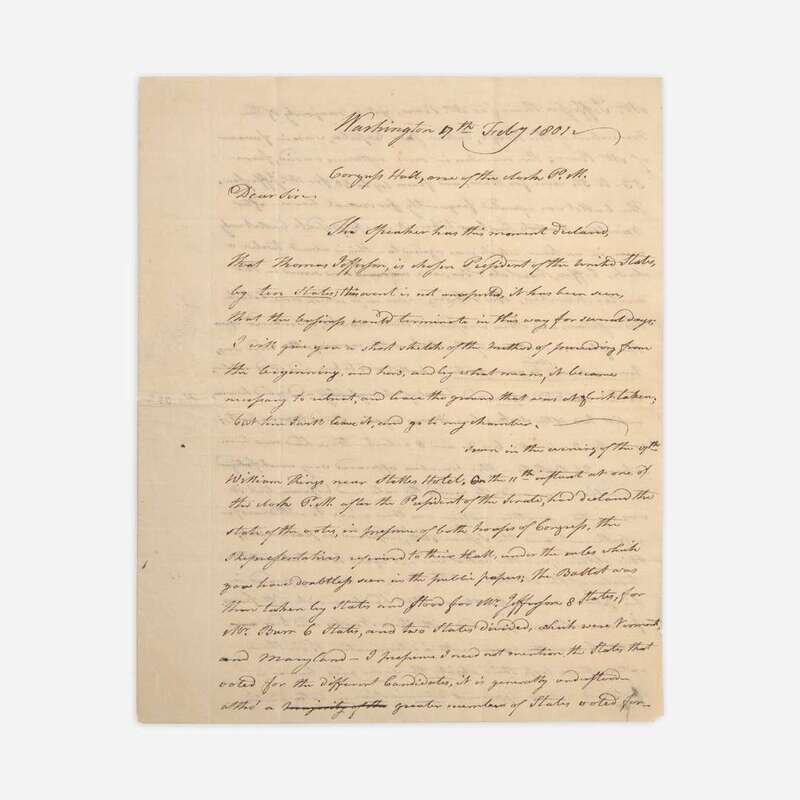

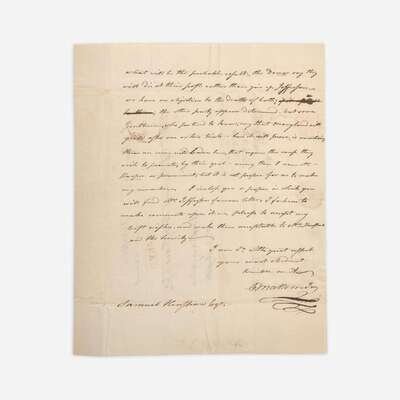

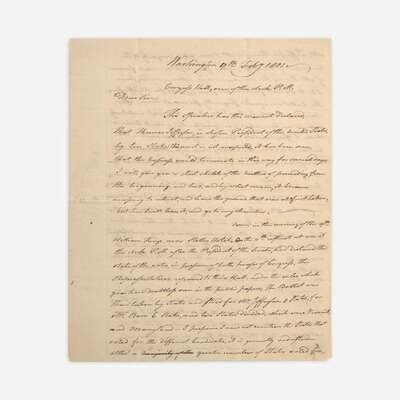

"The Speaker has this moment declared, that Thomas Jefferson, is chosen President of the United States..."

An unpublished eyewitness account of the election of Thomas Jefferson by the House of Representatives during the tumultuous presidential contest of 1800

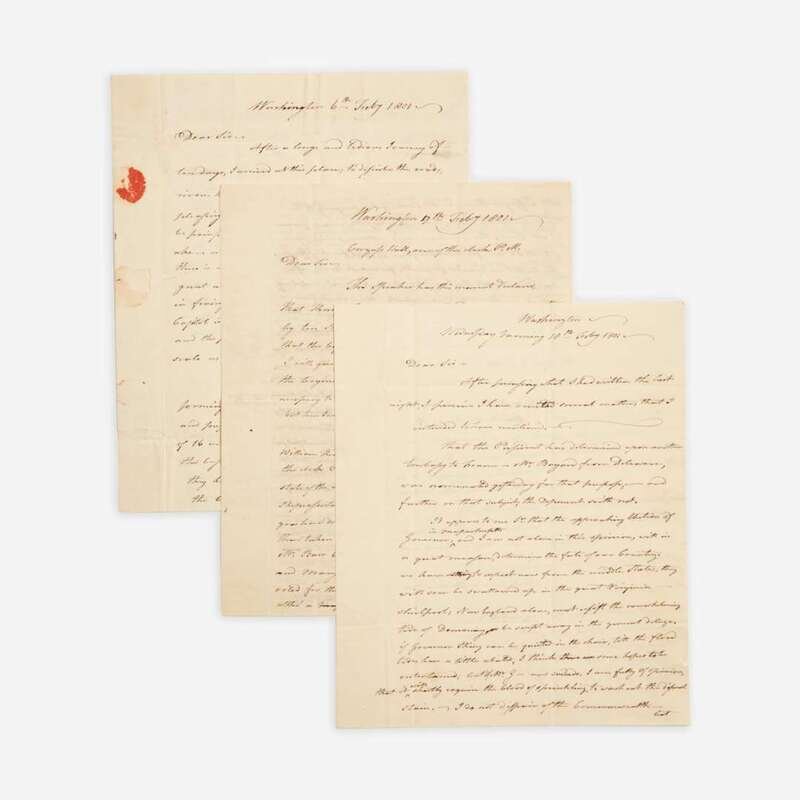

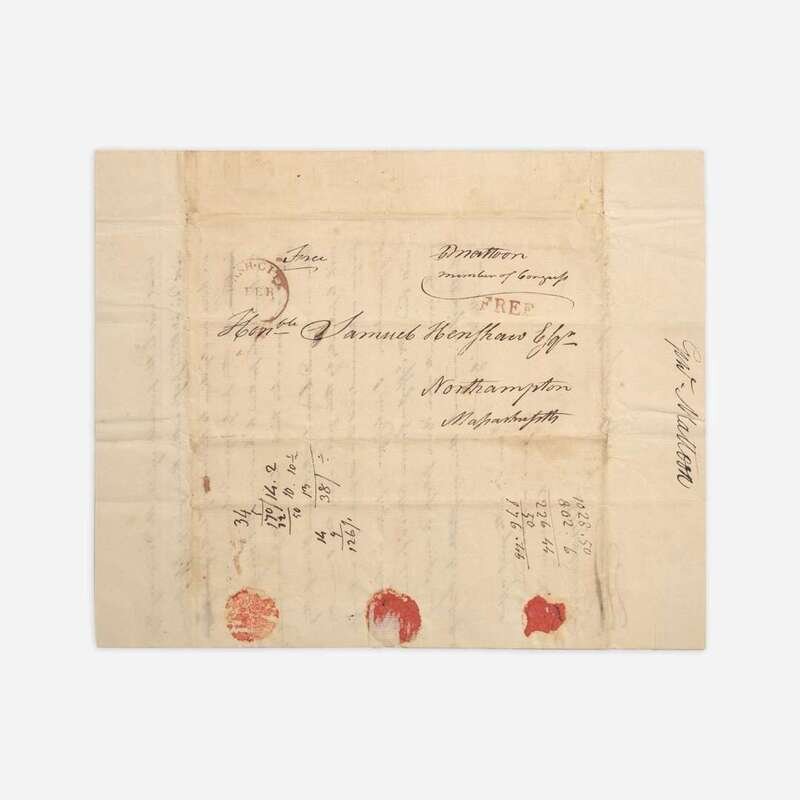

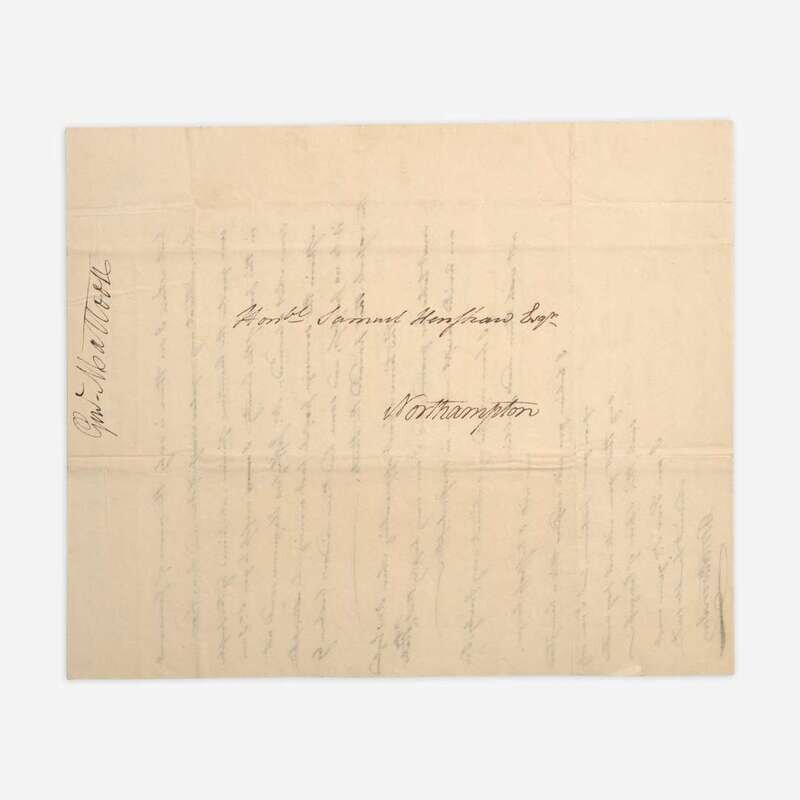

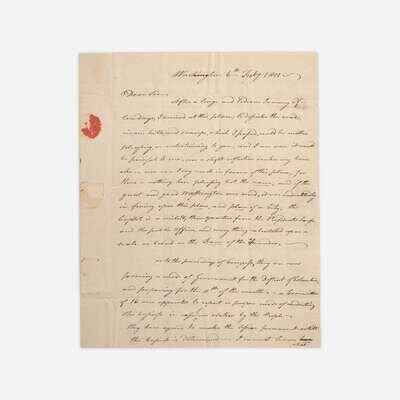

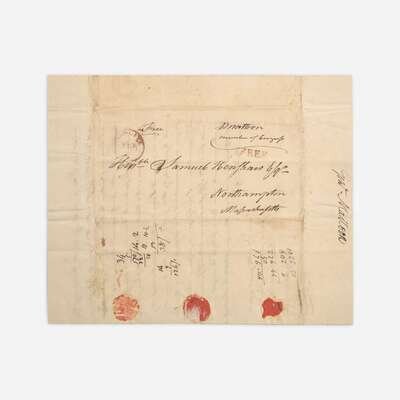

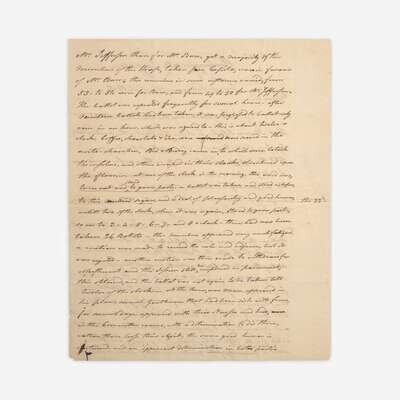

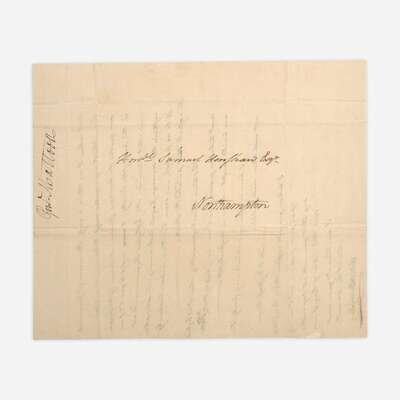

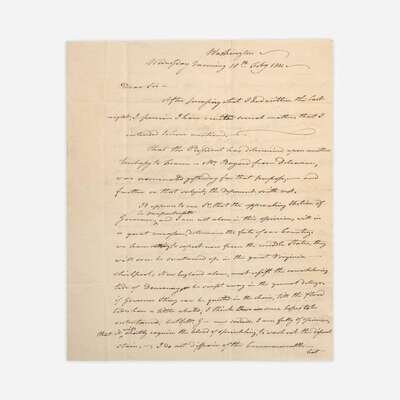

Washington, (D.C.), February 6, 17, and 18, 1801. Comprising three autograph letters, signed by Massachusetts congressman Ebenezer Mattoon, to his friend, the Northampton, Massachusetts judge Samuel Henshaw; concerning Mattoon’s recent arrival in the new capital city, the ongoing political upheaval resulting from the undecided presidential election of 1800, and an important descriptive account of the House of Representative's voting process to resolve the matter, resulting in the election of Thomas Jefferson as the third president. Each letter measuring 9 7/8 x 8 1/8 in. (251 x 206 mm); two letters addressed by Mattoon on integral leaf, one free-franked by Mattoon and with remnants of original wax seals; docketing to each, presumably in Henshaw's hand; creasing from contemporary folds; letter of February 17 separated along center vertical fold; other scattered minor wear and short tears.

A gripping account of Washington, D.C. in turmoil during the bitter presidential election of 1800, including a detailed eyewitness account of Thomas Jefferson's election by the House of Representatives, written less than an hour following his victory.

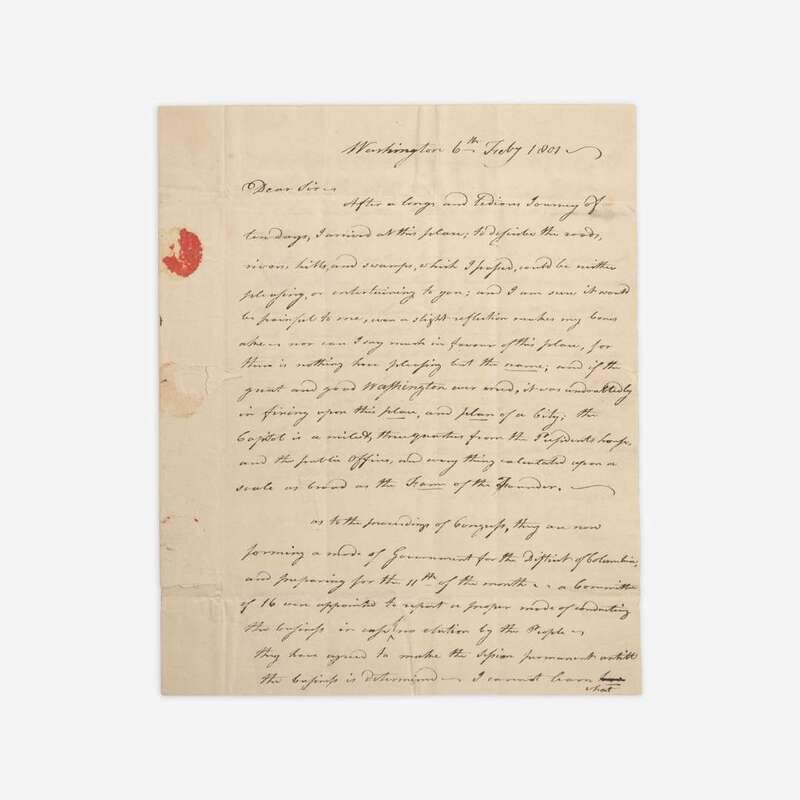

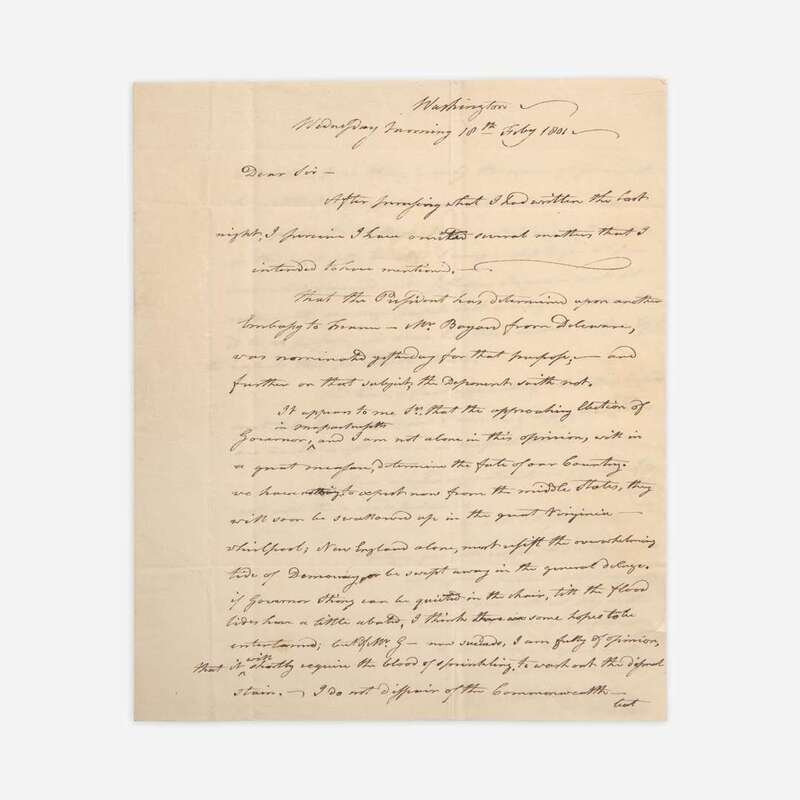

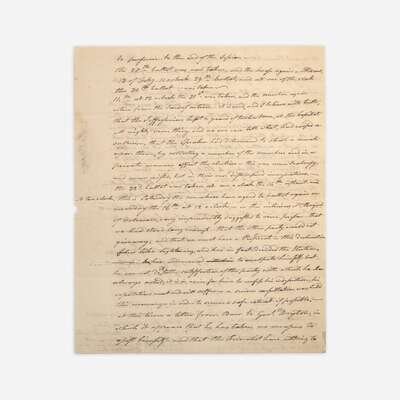

Ebenezer Mattoon (1755-1843) was a Massachusetts Federalist, newly elected to the Sixth Congress in a special election, when he first arrived in Washington, D.C., in early 1801. "After a long and tedious Journey of ten days," Mattoon took office in the new capital city on February 2, four days before he began penning the first of these three letters to his friend and confidant, the pastor-turned-judge Samuel Henshaw (1744-1809). Upon his arrival Mattoon found the new capital city, "nothing more pleasing than the name; and if the great and good Washington ever erred, it was undoubtedly in fixing upon this place, and plan of a City..." At the time of Mattoon's arrival Washington, D.C. was beset by bubbling anxiety stemming from the electoral tie between Republican presidential nominee Thomas Jefferson and his Republican running mate, Aaron Burr, in the previous year's presidential election. In order to determine who would become the third president the matter was sent to the House of Representatives for a special election to be held that upcoming February, by a Congress that was then dominated by a lame duck Federalist majority who had just seen their candidates, John Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, defeated. In the weeks following the electoral tie, in December 1800, it became clear to both the Federalists and the Republicans in Congress that neither Jefferson nor Burr carried a majority of states to win outright in the upcoming House vote. As the February session neared, Jefferson had the support of eight state delegations (one less than the majority needed to win), and Burr--largely because of disaffected Federalists--had the support of six. Both Maryland and Vermont's delegations were deadlocked and the matter was at an impasse. After weeks of fruitless backroom negotiations to change votes before the House session began, Mattoon--who likely supported Burr as the lesser of two evils, like most Federalists--vented to Henshaw of his frustration, sardonically stating that "the Demos say they will die at their posts, rather than give up Jefferson, we have no objection to the Death of both; the other party appears determined--but some Gentlemen...say that Maryland will yield after one or two trials--how it will prove, is uncertain."

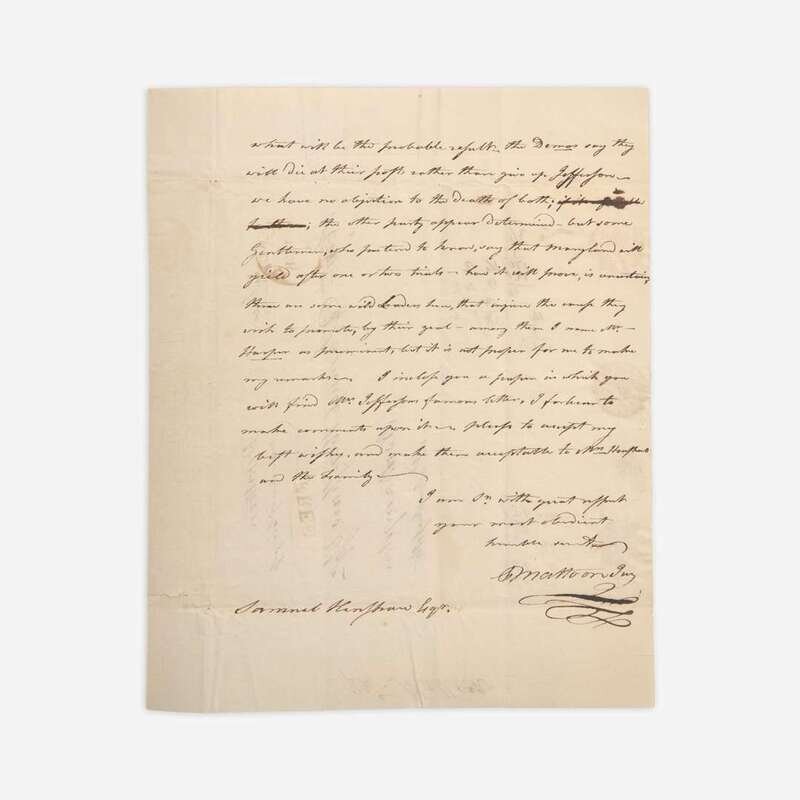

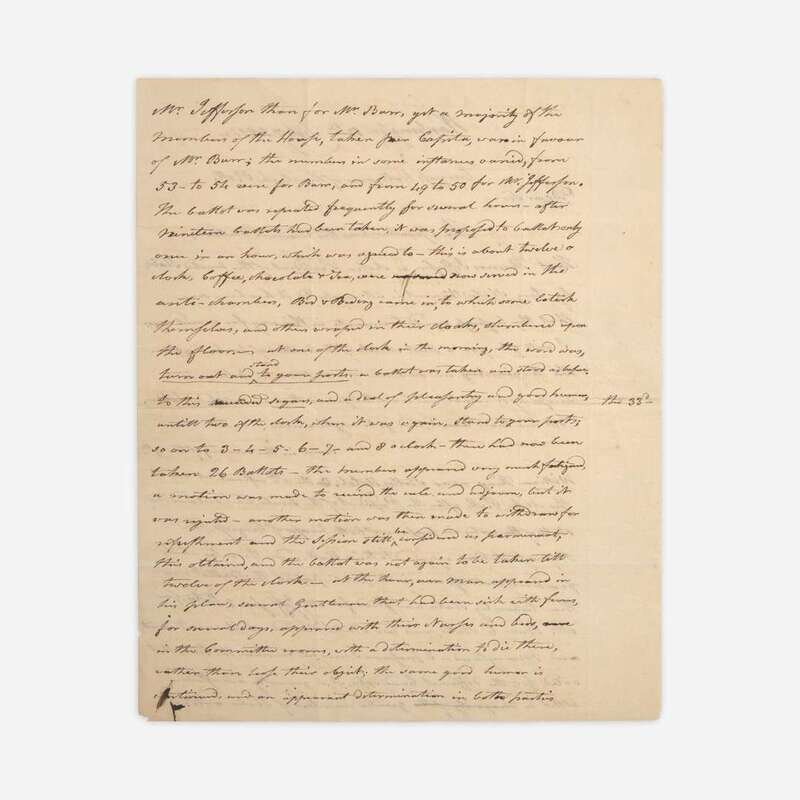

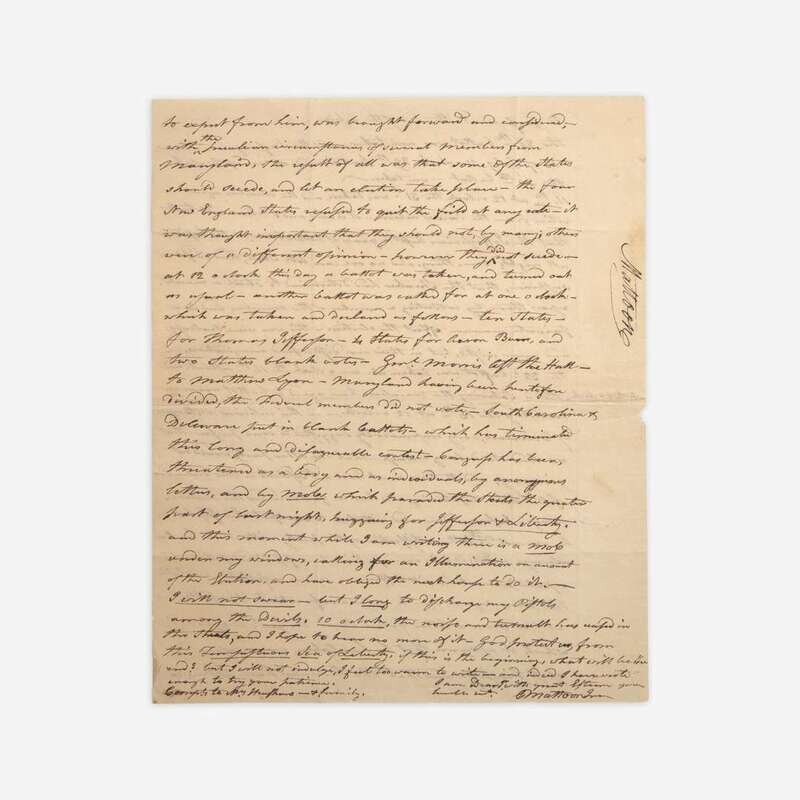

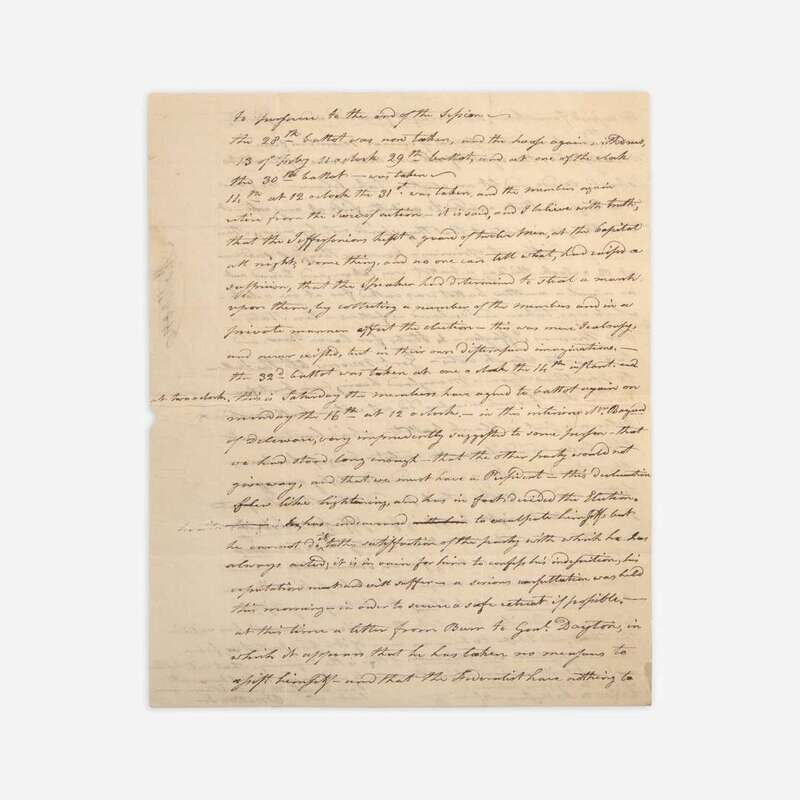

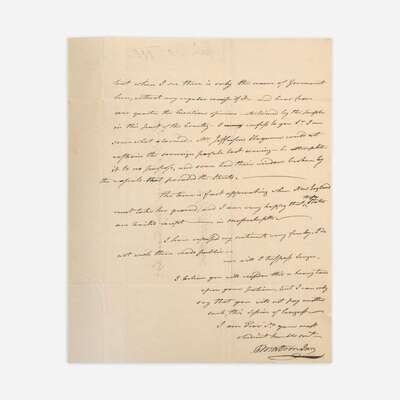

Beginning at noon on Wednesday, February 11, Congress convened to begin voting. Over the next six days, 35 ballots were taken, each with the same deadlocked results. During those intervening days a deepening frustration set in among Congress, and rumors of anti-democratic plots and usurpations to settle the matter began to swirl throughout Washington, D.C. Negotiations reached a fever pitch that weekend, until finally, with the abstention of Delaware's single delegate, James Bayard, the deadlock was resolved in favor of Jefferson. On the 36th ballot, taken at noon on Tuesday the 17th, the House elected Thomas Jefferson third President of the United States. Mattoon opens his second letter less than an hour after that critical vote, written in "Congress Hall, one of the clock P.M." Mattoon informs Henshaw that, "The Speaker has this moment declared, that Thomas Jefferson, is chosen President of the United States." He continues to painstakingly recount the previous day's events leading up to that momentous vote: "The ballot was repeated frequently for several hours--after nineteen ballots had been taken, it was proposed to ballot only once in an hour, which was agreed to--this is about twelve o clock, Coffee, chocolate, & Tea, were now served in the ante-chambers, Bed & Beding (sic) came in, to which some betook themselves, and others wrapped in their cloaks, slumbered upon the floor..." Describing the stakes at hand and the need for every congressman to be present for voting, Mattoon writes that, "several Gentlemen that had been sick with fevers, for several days, appeared with their Nurses and beds, in the Committee rooms, with a Determination to die there, rather than loose (sic) their object...an apparent determination in both parties to persevere to the end of the session." Mattoon goes on to describe Bayard's decision to change his stance: "Mr. Bayard of Delaware, very imprudently suggested to some person--that we had stood long enough--that the other party would not give way, and that we must have a President--this declaration flew like lightening (sic), and has in fact decided the Election. He has endevoured to exculpate himself, but he cannot do it to the satisfaction of the party with which he has always acted; it is in vain for him to confess his indiscretion, his reputation must and will suffer..." Mattoon summarizes the final vote that gave the election to Jefferson, "ten States--for Thomas Jefferson--4 States for Aaron Burr, and two States blank votes...Maryland having been heretofore divided, the Federal members did not vote,--South Carolina & Delaware put in blank ballots--which has tirminated (sic) this long and disagreeable contest." In a final lamentation to Henshaw, Mattoon writes, "God protect us, from the Tempestuous Sea of Liberty, if this is the beginning, what will be the end?"

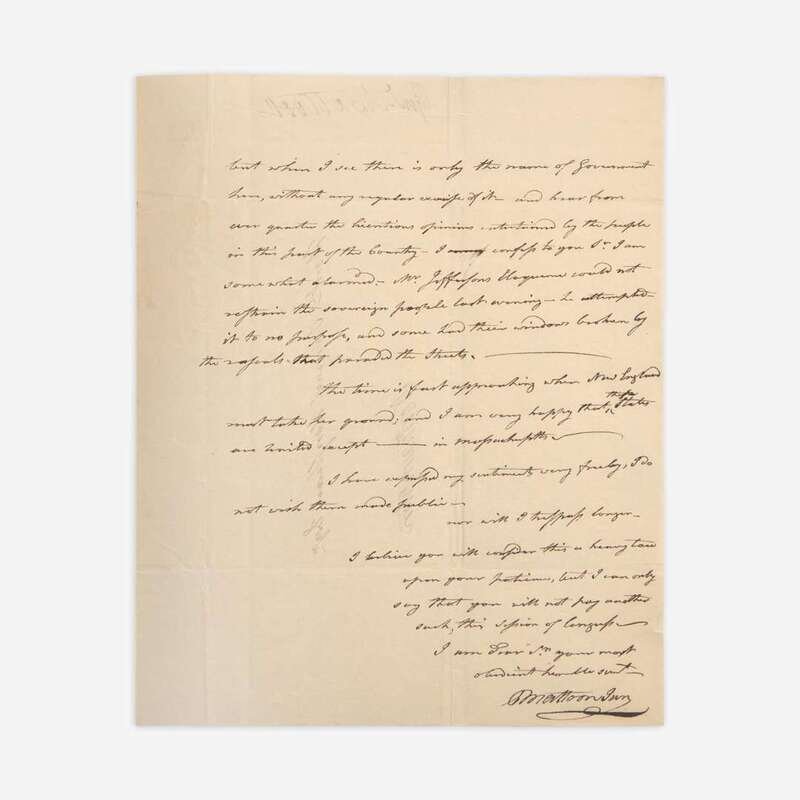

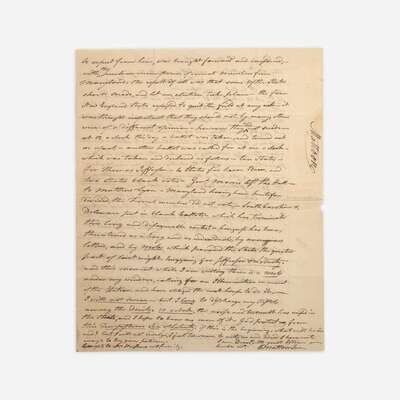

Mattoon pens his third letter the morning following this hotly contested and historic election, on Wednesday, February 18, after what was likely a sleepless and bitter night listening to crowds of Jefferson supporters parade through the streets in celebration. He describes his frustration concerning the evening’s crowds: "Mr. Jeffersons Eloquence could not restrain the sovereign people last evening--he attempted it to no purpose, and some had their windows broken by the rascals that paraded the streets." In the aftermath of Jefferson's victory Mattoon details his opinion of what his victory means for the country, as well as his thoughts on the upcoming gubernatorial election in Massachusetts between Federalist Caleb Strong and Republican Elbridge Gerry: "We have nothing to expect from the middle States, they will soon be swallowed up in the great Virginia--whirlpool; New England alone, must resist the overwhelming tide of Democracy or be swept away in the general deluge...I do not dispair (sic) of the Commonwealth--but when I see there is only the name of Government here, without any regular exercise of it...The time is fast approaching when New England must take her ground; and I am very happy that the States are United except--in Massachusetts." Mattoon finishes his letter by hoping Henshaw will not betray his candor, "I have expressed my sentiments very freely I do not wish them made public."

Although the presidential election of 1800 was long and bitter, the transfer of power was peaceful. To prevent similar tied results in future elections, the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, that separated electoral votes between President and Vice President, was ratified in 1804.

A unique and unpublished insider's account of an historic moment during one of America's most divisive presidential elections.