Condition Report

Contact Information

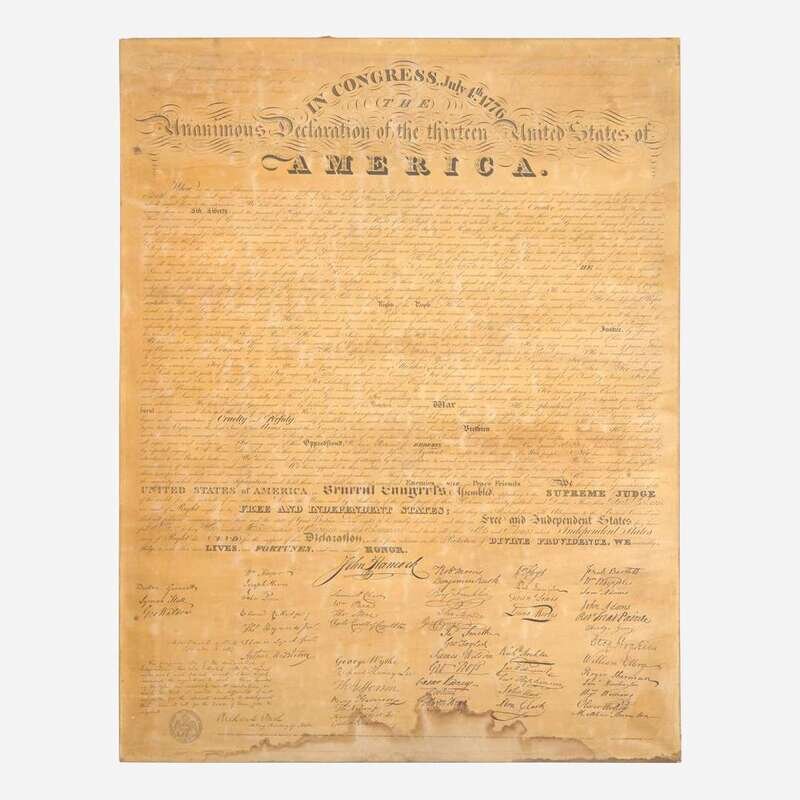

Lot 4

Lot Description

The First Facsimile Printing of the Declaration of Independence

(Washington, D.C.): Benjamin Owen Tyler, 1818. Engraved broadside on paper. Engraved by Peter Maverick of Newark, New Jersey, after Tyler's design. Sheet mounted to linen and wooden frame; sheet unevenly browned; open tear and wear along top left corner and edge of plate-mark; several old repairs along bottom edge; three-inch tidemark along bottom edge; corners clipped when stretched over wooden frame. Bidwell 2

A scarce copy of Benjamin Owen Tyler's famed printing of the Declaration of Independence, the first facsimile engraving of America's founding charter. Tyler used the original engrossed Declaration--created in August 1776--to create his engraving, carefully copying the text, and for the first time, faithfully rendering its 56 signatures. After Tyler received the endorsement of Thomas Jefferson for this work, he chose to dedicate it to him: "To Thomas Jefferson, Patron of the Arts, the firm Supporter of American Independence, and the Rights of Man, this Charter of our Freedom is, with the highest esteem, most Respectfully Inscribed by his much Obliged and very Humble Servant Benjamin Owen Tyler." Engraved in the bottom left corner is a note from Acting Secretary of State, Richard Rush (brother to Founder, Benjamin Rush) certifying the accuracy of the text and the signatures: "The foregoing copy of the declaration of Independence, has been collated with the original instrument and found correct. I have, myself, examined the signatures to each. Those executed by Mr. Tyler are curiously exact imitations; so much so that it would be difficult if not impossible for the closest scrutiny to distinguish them, were it not for the hand of time, from the originals."

Although the text of the Declaration was first printed by John Dunlap in July 1776, it would be over 40 years before the average American could see or own a printed version that closely resembled the original document, and for the first time, see the signatures of 56 of the country's Founding Fathers. Tyler's publication was preceded by a bitter contest between himself and his business rival, John Binns, over who would be the first to print a facsimile version of the Declaration, and gain the endorsement of its principal author, Thomas Jefferson. While Binns began work on his highly decorative print in 1816, he failed to publish it until 1819, a year after Tyler's inexpensive and less ornamental engraving. Both Tyler and Binns's prints reflected a period of growing American nationalism during the Era of Good Feelings. Following the War of 1812, when the nation was approaching 50 years of independence, and as the Revolutionary generation was passing away, American citizens began to look back in reverence to the country's founding documents as a source of national pride and purpose. Tyler and Binns looked to take advantage of this patriotic spirit by publishing prints relating to the Revolutionary era, and their famous works were followed by many imitators. Importantly, in 1823, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had an official facsimile edition of the engrossed Declaration printed by William J. Stone.