Lot 6

General George Washington's Orders Concerning Deserters, Relayed By A Continental Army Officer Encamped at Valley Forge

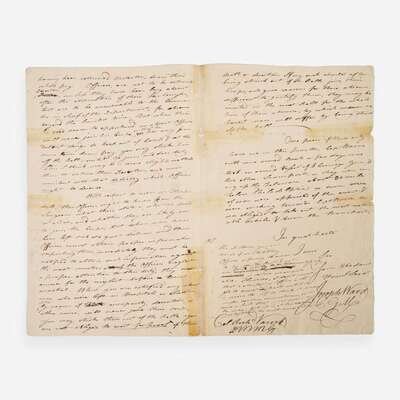

"I consulted his Excellency general Washington on these matters, and his direction was, that Soldiers who did not join their Corps at the expiration of their Furloughs...should be returned Deserters...With respect to men in Hospitals, their Officers ought to know from the Surgeons what their state is, whether dead or alive, and whether they are likely ever to join the Corps..."

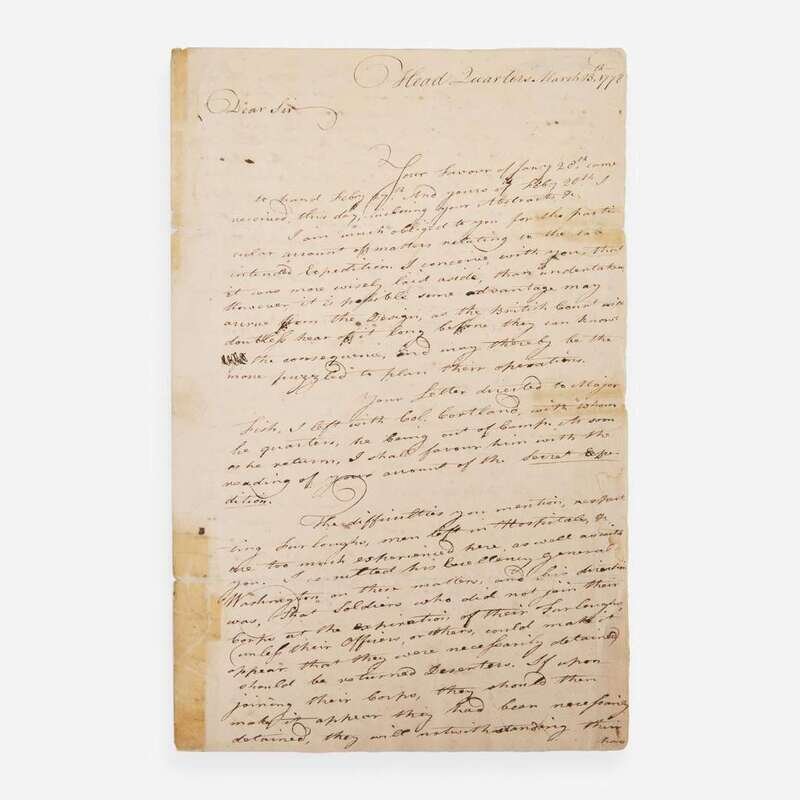

(Valley Forge, Pennsylvania): Head Quarters, March 13th, 1778. One sheet folded to make four pages, 11 3/4 x 7 5/8 in. (298 x 194 mm). Autograph letter, signed by Joseph Ward (1737-1812), C(ommissary). G(eneral). (of) M(usters)., to Col(onel). Rich(ar)d. Varick (1753-1831), D(eputy) M(uster) M(aster) G(eneral) at West Point, New York, relaying orders from General George Washington concerning missing and deserting troops at the Valley Forge winter encampment; docketed on verso. Creasing from contemporary folds, separations and old tape repairs to same, but now removed and conserved; a few small dampstains and traces of mounting in left margin.

Head Quarters March 13th, 1778

Dear Sir

Your favour of Jany 28th, came to hand Febry 27th. And yours of Febry 20th. I received this day, inclosing your Abstracts &c.

I am much obliged to you for the particular account of matters relating to the late intended Expedition. I conceive, with you, that it was more wisely laid aside, than undertaken. However, it is possible some advantage may accrue from the Design, as the British Court will doubtless hear of it long before they can know the consequence, and may thereby be the more puzzled to plan their operations.

Your Letter directed to Major Fish, I left with Col. Cortland, with whom he quarters, he being out of Camp. As soon as he returns, I shall favour him with the reading of your account of the Secret Expedition.

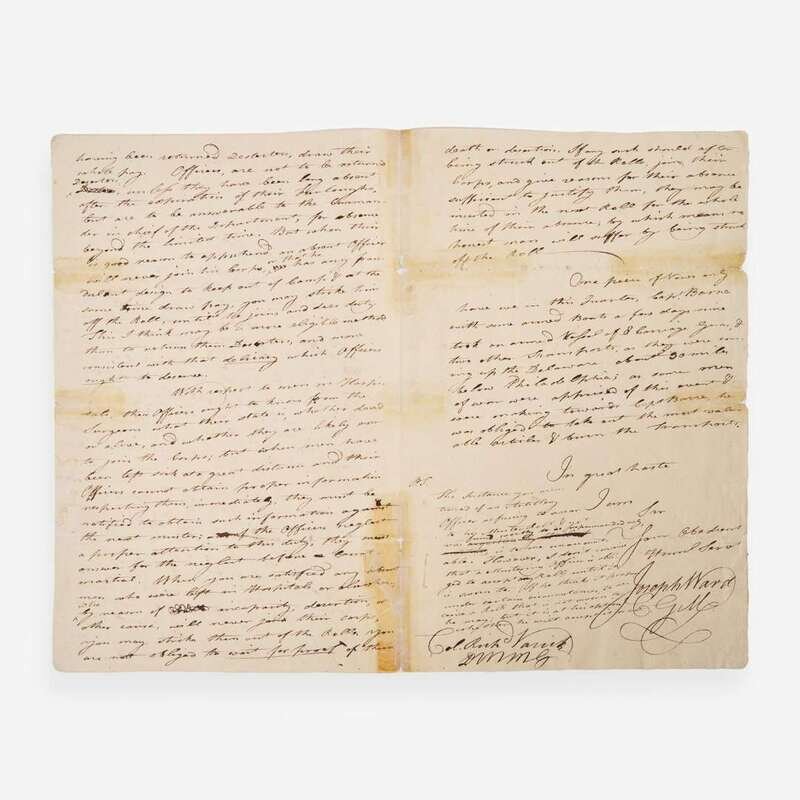

The difficulties you mention, respecting Furloughs, men left in Hospitals, &c., are too much experienced here, as well as with you. I consulted his Excellency general Washington on these matters, and his direction was, that Soldiers who did not join their Corps at the expiration of their Furloughs, (unless their Officers, or others, could make it appear that they were necessarily detained) should be returned Deserters. If upon joining their Corps, they should then make it appear they had been necessarily detained, they will notwithstanding their having been returned Deserters, draw their whole pay. Officers, are not to be returned Deserters, unless they have been long absent after the expiration of their Furloughs, but are to be answerable to the Commander in chief of the Department, for absence beyond the limited time. But when their (sic) is good reason to apprehend an absent Officer will never join his Corps, or that he has any fraudulent design to keep out of Camp & at the same time draw pay, you may strike him off the Roll, until he joins and does duty. This I think may be a more eligible method than to return them Deserters, and more consistent with that delicacy which Officers ought to deserve.

With respect to men in Hospitals, their Officers ought to know from the Surgeons what their state is, whether dead or alive, and whether they are likely ever to join the Corps; but when men have been left sick at a great distance and their Officers cannot obtain proper information respecting them, immediately, they must be notified to obtain such information against the next muster; and if the Officers neglect a proper attention to this duty, they must answer for the neglect before a Court-martial. When you are satisfied any absent men who were left in Hospitals or elsewhere, who by reason of incapacity, desertion, or other cause, will never join their corps, you may strike them out of the Rolls, you are not obliged to wait for proof of their death or desertion. If any such should after being struck out of the Rolls, join their Corps, and give reasons for their absence sufficient to justify them, they may be inserted in the next Roll for the whole time of their absence; by which means no honest man will suffer by being struck off the Roll–

One piece of News only have we in this Quarter, Capt. Barre (sic) with some armed Boats a few days since took on armed Vessel [sic] of 8 Carriage Guns, & two other Transports, as they were coming up the Delaware about 30 miles below Philadelphia; as some men of war were apprised of this event & were making towards Capt Barre (sic), he was obliged to take out the most valuable articles & burn the Transports.

In great haste

I am Sir Your Obedient Humb Servt

Joseph Ward C.G.M.

P.S. The Instance you mentioned of an Artillery Officer refusing to swear to his Muster Roll, & yet was found worthy to be reprimanded only, is to me unaccountable. However, I don’t conceive that a Mustering Officer is obliged to accept any Roll until it is sworn to. If he thinks it proper under certain circumstances, to receive a Roll that is not sworn to, he may; but it is at his option whether he will accept it or not.

Col. Richd Varick DMMG

Written from Valley Forge at the close of the infamous winter of 1777-78, Commissary General of Musters Joseph Ward relays Washington’s directions for determining the status of missing men, when they should be labeled as deserters, and protocol for those returning to duty from camp hospitals. Valley Forge, situated 18 miles northwest of Philadelphia, was the first prolonged winter encampment that the Continental Army endured. Nine thousand men were quartered for a six-month period, and during that time some 2,000 American soldiers died from exposure, hunger, or disease. By early 1778, the condition and morale of the troops had reached their lowest point. The supply system was in a state of collapse; many of the troops and officers were unpaid; there was poor hygiene, malnourishment, and communicable diseases; and mutiny loomed as a real possibility. As spring approached, the situation began to turn with the arrival of Prussian drillmaster Baron von Steuben (1730-1794) in late February. Von Steuben, appointed acting inspector general, instituted a strict system that gradually brought a greater sense of professionalism to the ranks. The troops who survived Valley Forge emerged seasoned, disciplined, and were a far cry from the untrained men who straggled into the camp in December of 1777.

In addition to soldiers who were missing or possibly deserted, a large population of soldiers were being treated at the hospitals set up at Valley Forge. A primary concern of Washington and other Continental officers was keeping an up to date account of the army's muster rolls in order to know how many men were battle ready. Two thirds of the deaths that occurred during the 1777-78 encampment were the result of rampant diseases such as influenza, typhus, or dysentery. George Washington issued a myriad orders regarding the camp's sanitation, such as requiring weekly affliction reports, quarantining the sick, designating specific latrine areas, disinfecting drinking water, airing out residential huts, burning kitchen waste, and more. Despite the best efforts, men were constantly getting sick, and unable to perform their duties or training. The surgeons of regiments were most often responsible for keeping track of the status of men in the camp, and reporting to their superiors those who were "dead or alive", or "likely ever to join the Corps."

The account of naval activity mentioned by Ward involved Captain John Barry, who was commander of the Brig Lexington. In early March, Barry had surprised two British armed supply ships and an armed schooner, the Alert. Barry’s 27 men boarded and captured all three vessels, including the 116 men aboard the Alert. Though forced to burn the transports to prevent them from falling back into enemy hands, Barry was able to report to Washington of the venture’s overall success.The “Secret Expedition” cited here was likely Spencer’s Expedition, a late 1777 plan to surprise the British in Rhode Island.

Desertion was a major issue for the Continental Army in the early years of the war. The unprofessional composition of local militias and volunteer troops caused problems for the Americans as they were rebelling against one of most well-trained and equipped armies of the era. In the introduction to his 2009 book, He Loves a Good Deal of Rum: Military Desertions During the American Revolution 1775-1783, historian Joseph Lee Boyle writes, ‘‘Service in the Continental Army was indeed the stuff of legend for the fortitude and perseverance of those who stayed. Hardships due to poor or nonexistent food and clothing, infrequent paydays, rampant monetary inflation, fear of combat, homesickness, family problems, crowded unsanitary life in camp, and rampant disease were all contributing factors to soldiers refusing to join or abruptly leaving military life.’’ Some modern academic studies suggest that as many as 20-25% of soldiers in the Continental Army deserted at some point over the eight-year conflict. However, due to the constant and chronic demand for fighting men, at times commanders were forced to be lenient with deserters. Officers were granted more leeway before being labeled a deserter than the common soldier, which as Ward says was a "delicacy which Officers ought to deserve."

Letters written from Valley Forge are rare, particularly if they relate to the condition of the troops.

Provenance

Sotheby's, New York, The James S. Copley Library: Magnificent American, Historical Documents: Third Selection, May 20, 2011 Sale No. 8708, Lot 1033