Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 74

Lot Description

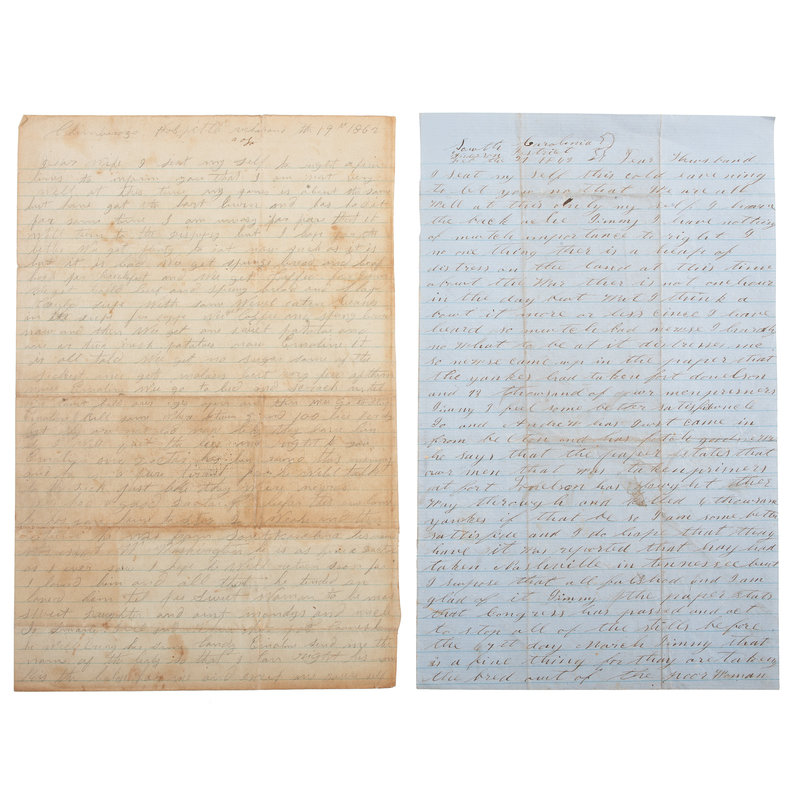

Lot of 49 letters, the majority of which are Civil War-dated and written by CSA Private James M. Geer, Co. L, 1st South Carolina Regiment Rifles. Also with letters Geer received from his wife, Martha Emeline, and other family members. Plagued by illness during his service, Geer spent several months at Richmond’s famed Chimborazo Hospital, and his correspondence offers a fascinating perspective on the medical care he and his fellow soldiers received, both at this facility and in the field.

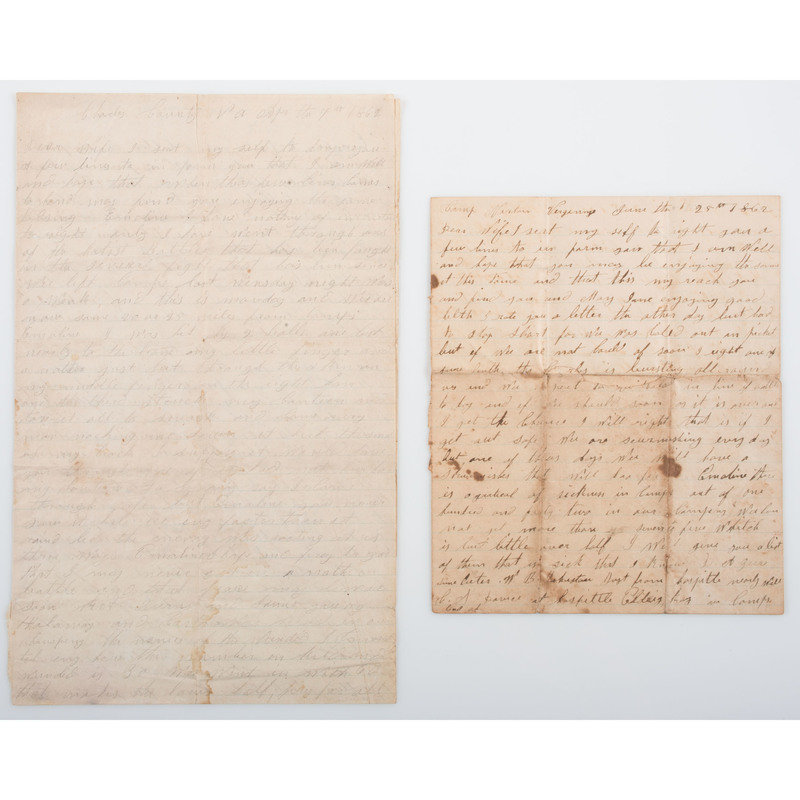

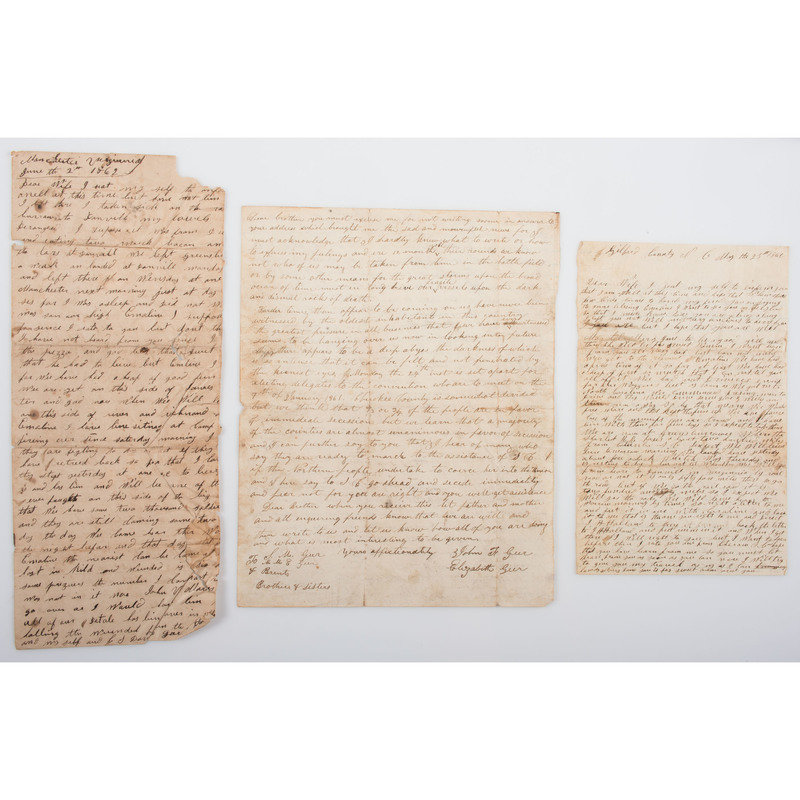

James Monroe Geer (ca 1829-1863), a resident of Anderson County, SC, enlisted on January 7, 1862, leaving behind Emeline (1835-1905) and Mary Jane (1859-1936), his young daughter. Prior to his enlistment, older brother John Franklin Geer wrote with news from Alabama of secessionist sentiments that would ultimately pervade the South: “Cherokee County is somewhat divided but we think that 2/3 or 3/4 of the people are in favor of secession. . . and I hear of many who say they are ready to march to the assistance of S.C. if the Northern people undertake to cower her into the Union and, I have to say to S.C. go ahead and secede immediately and fear not for you are right and you will get assistance.” Upon secession and the outbreak of the Civil War, brother David Geer enlisted in the 1st Regiment Rifles as a sergeant and was stationed in Charleston. In letters to his brother, David describes the capture of Port Royal and shares his own motivations for serving the Confederacy: “We have liberty [and] we wish to maintain it...there is only two sides to the question. We will have to take one of them, we will either have to be subjects to King Abe or be an independent people so if we have to Battle for freedom let us do it with cheerfulness and depend on god to decided which is right.” Undoubtedly influenced by his older brother, James Geer volunteered for service and joined the same company.

The 1st Regiment Rifles, also known as Orr’s Rifles, was organized in July of 1861 at Camp Pickens in Sandy Springs, SC, drawing recruits from Abbeville, Anderson, Marion, and Picken counties. In addition to his brother David, Geer served alongside his nephew and many other close family friends from Anderson County, to whom he refers frequently in his letters. His earliest epistolary exchanges with Emeline come from Sullivan’s Island, where his unit was first stationed. Called “The Pound Cake Regiment” by other troops because of its initially light duties there, Orr’s Rifles continued to attract volunteers, mustering in over 1,500 men by the beginning of 1862. Geer’s letters from this time primarily concern the food he eats (“I am well and getting fat, my pants has got so tite that I can hardly bare them buttoned”), family finances, discussions of the weather, and requests for news from home. On January 24, 1862, Emeline obliges, announcing her pregnancy (“You wanted to no whether I was in the family way or not I think that I am” ), and concern for her health becomes a prevailing trend in Geer’s subsequent letters.

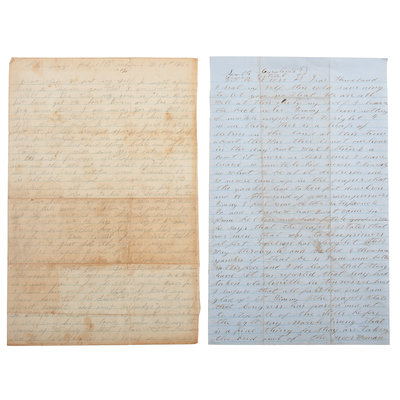

Emeline writes again to “Jimmy” on February 21, 1862, fearful for his safety amid reports of Union advances: “There is a heap of distress on the land at this time about the War. . . it came up in the papers that the Yankees had taken fort Donelson and 13 thousand of our men prisoners. . . Jimmy they say that the Yanks is going to pitch in on Charleston and Savannah GA. Jimmy I am uneasy for fear that [they] can come in there and if they can come in I am afraid they will take you and all the rest prisoner.” Upon receipt of this letter, Geer assures her that his regiment is “throwing up breastworks on the Island in order to be ready if the enemy should attempt to land.”

In April of 1862, Orr’s Rifles moved to Virginia with 1,000 men, Geer included. His letters from this period were written at various locations throughout the state, including Charles County, where he shares gripping details of a battle near Mechanicsville along the murky Chickahominy River: “I went through one of the hardist Battles that has been fought. . . I was hit by 2 balls one but nearly to the hand, my little finger and another just but through the skin on my middle finger on the right hand, and the third struck my canteen and tore it all to smash and came very near to knocking me down.” Though unscathed in this exchange, Geer notes that over half of the men in his unit are wounded or sick, including David, and in a letter from Camp Norton, VA, he describes the substandard medical care he witnessed in the field, declaring that the doctors “would just as soon see us die as to go to our tents to see us. . . unless there is better [attention] given all of the sick will die. I will lie under a tree in the woods before I will go to the hospital. They don’t keep the flies off and when the get so they cannot [raise] their hands the flies crawl in their mouths and nose.”

By July, Geer finds himself unwell, stricken first with severe joint pain and then paralysis of the lower extremities. On July 21, 1862, he writes to Emeline near Drewry’s Bluff that “we must get well the best way we can for our doctors has got so laysey that they wont walk one hundred yards to keep a man from dieing.” Though he participated in the Second Battle of Bull Run, Geer’s condition worsened, and in September, he was transferred to Chimborazo Hospital, where he spent the remainder of the year. Despite its reputation as a sophisticated, state-of-the-art facility, Geer tells his wife on November 15th that he has “stayed in the hospittle so long that [he] want[s] to get away from here.” In December, he enumerates his grievances, describing the food and substandard treatment: “I kill somewhere between 5 and 100 lice per day. . . one Doctor has been round this morning and he is a pure tyrant, for he will talk to the sick just like they were negros.” At then end of this letter, he notes that “there is a good case of small pox in these parts but there is none in Chimborazo Hospital.” Evidently, this good fortune did not hold, as Geer contracted small pox and died of the disease early in 1863 while still in Richmond.