[CIVIL WAR]. Corporal Samuel McKinney Stafford (1837-1922), 16th Ohio Battery, archive including war-date diary and letters.

Sale 2057 - American Historical Ephemera and Photography

Oct 25, 2024

10:00AM ET

Live / Cincinnati

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$1,500 -

2,500

Price Realized

$5,080

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

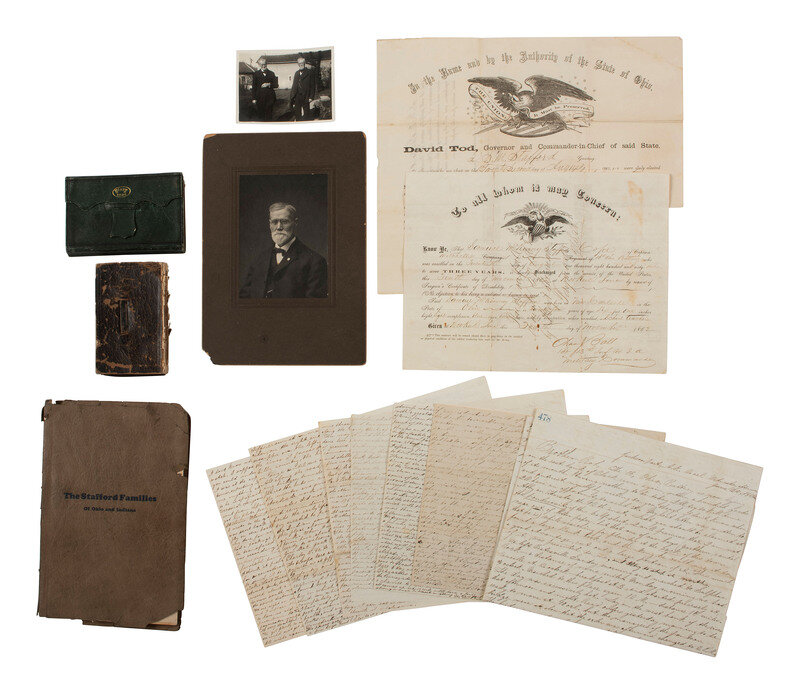

[CIVIL WAR]. Corporal Samuel McKinney Stafford (1837-1922), 16th Ohio Battery, archive including war-date diary and letters.

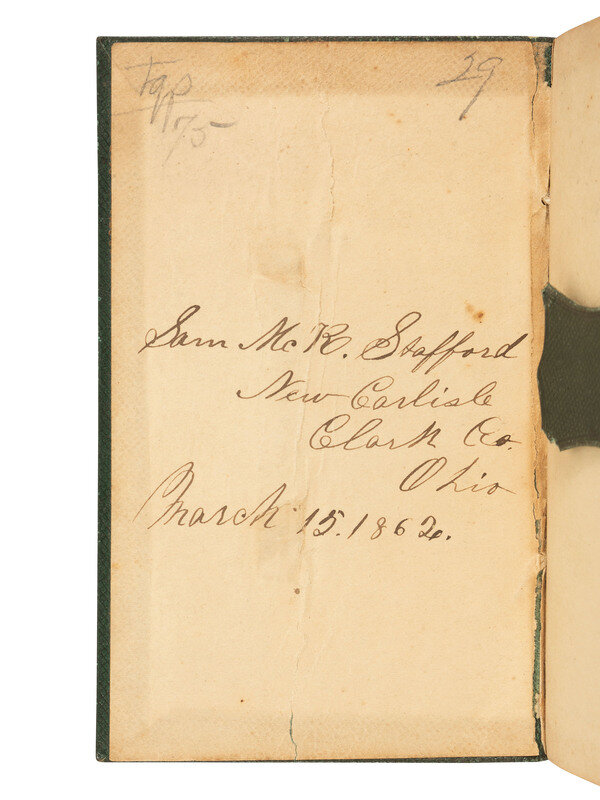

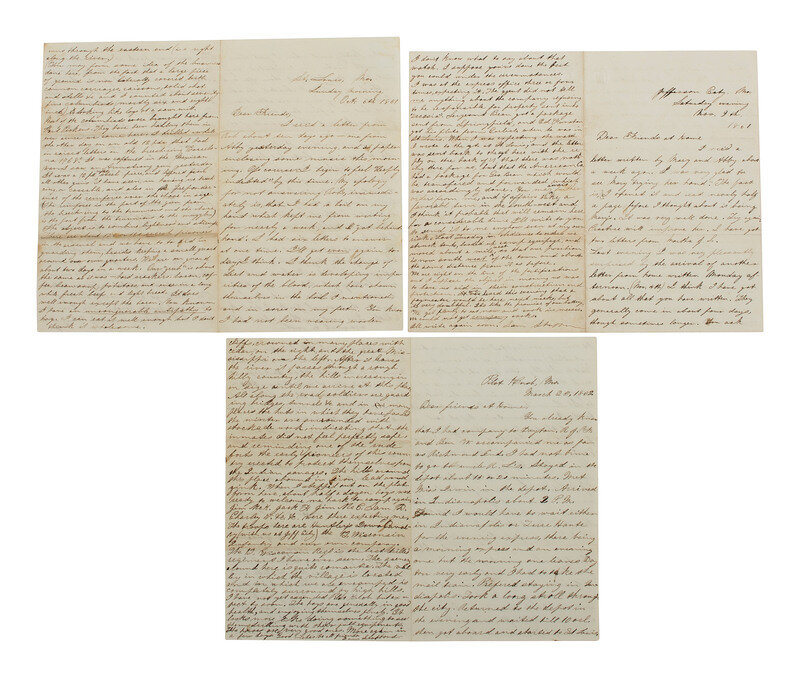

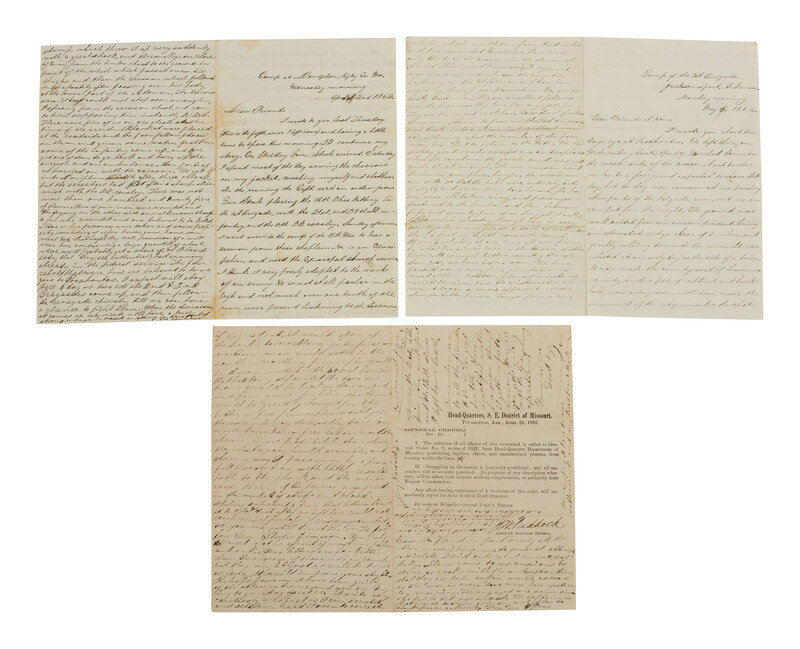

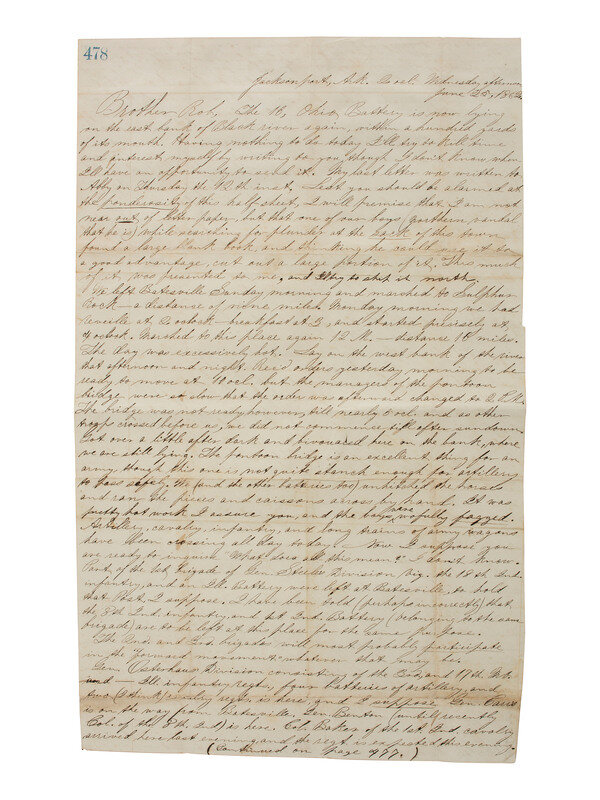

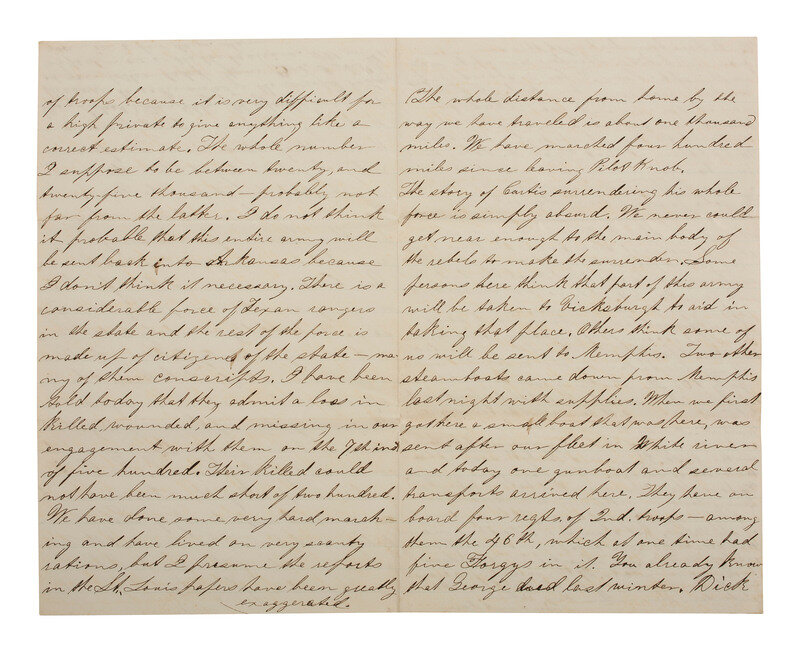

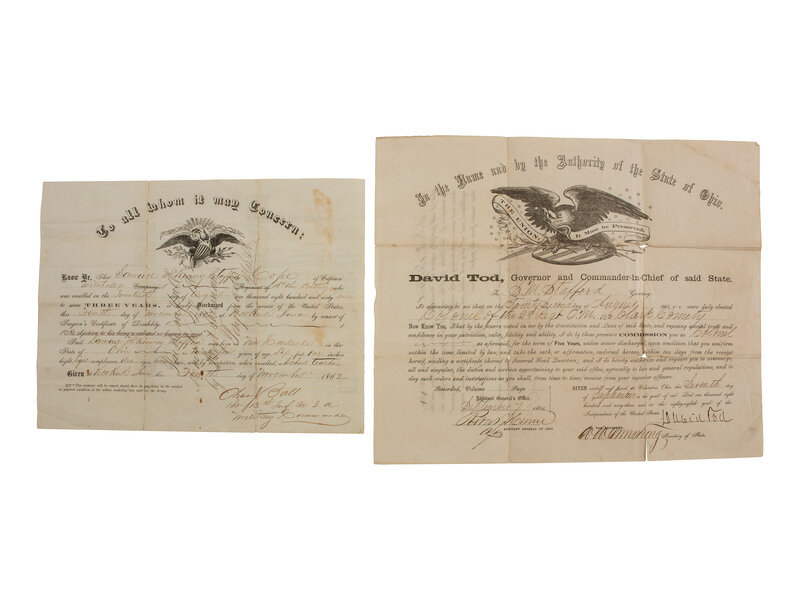

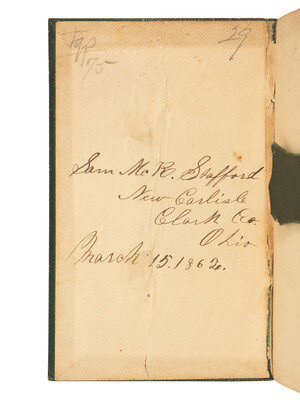

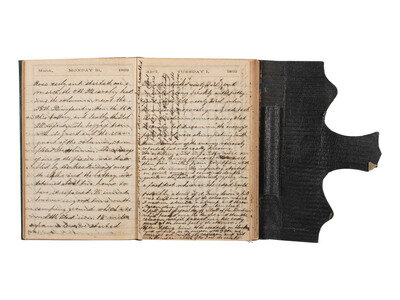

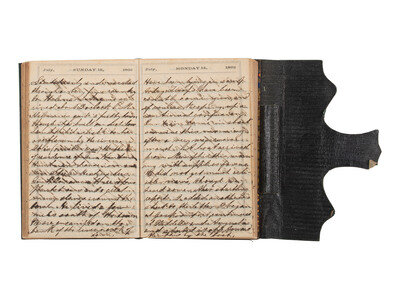

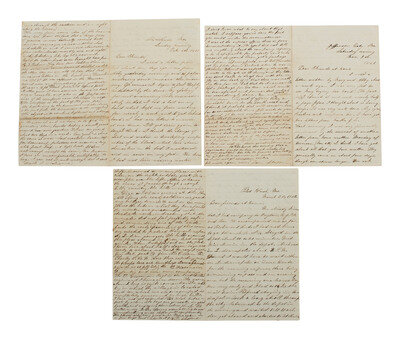

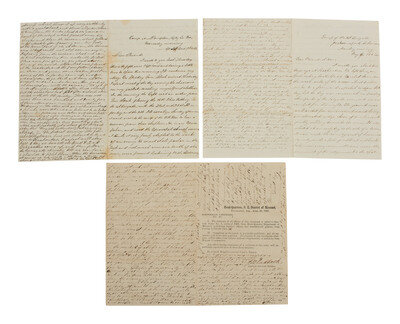

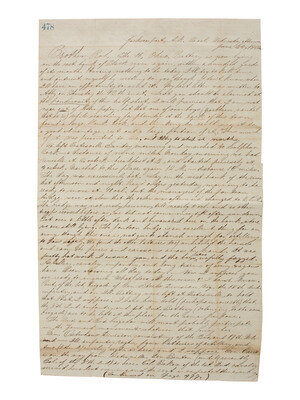

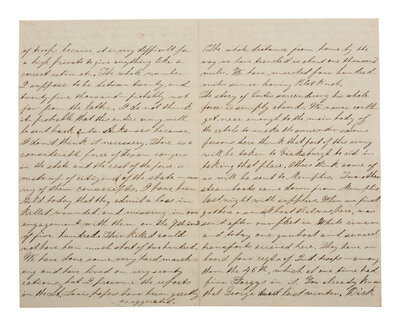

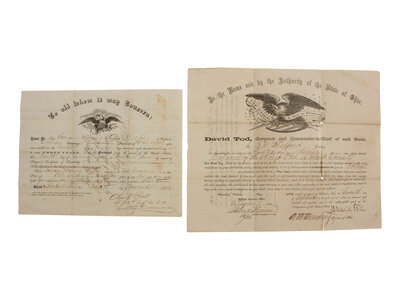

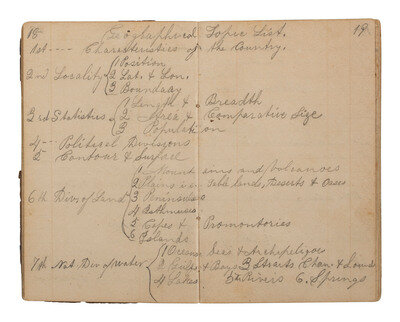

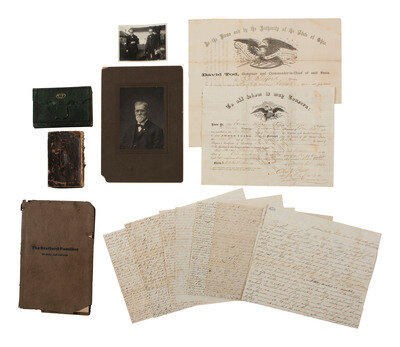

Pocket diary of Corporal Samuel M. Stafford, 16th Ohio Battery, spanning March 1862 - November 1862. 217pp utilized, entries in ink, one page per day format, 3 1/4 x 5 in., green leather cover, inscribed at front "Sam McK. Stafford / New Carlisle / Clark Co. / Ohio / March 15 1862." Accompanied by approximately 30 war-date letters, most 4pp+, written by Stafford to his family after his enlistment, spanning September 1861 through September 1862. Additional documents include Stafford's military discharge from the 16th Battery, Keokuk, Iowa, 4 November 1862, and his commission as Colonel of the 2nd Ohio Militia, Columbus, Ohio, 7 September 1863, signed by Ohio Governor David Tod. Letter and diary content is strong, particularly related to the conflict as it unfolded in Missouri and more remote areas of the Western Theater.

Stafford served in the Western Theater and, though he saw limited combat while he was enlisted, his letters remain exceptionally engaging. A school teacher prior to the war, Stafford is clearly an educated and articulate man with a keen sense of humor and his writings reflect these qualities. His earliest war-date writings are letters written shortly after his arrival in Missouri, a state deeply divided between northern and southern sympathizers and a hotbed of guerilla activity and civil unrest. Stafford writes from St. Louis, 15 September 1861, stating that "The laws are so strict that soldiers and officers are liable to arrest if found in the city without a written permission from their superiors....We can go without much risk by wearing our citizens dress." He is also struck by the "foreign population" of the city noting that German, Swiss, French, Irish, &c make up a large part of the population. As Stafford remains in St. Louis drilling, his letters then continue with discussion of the St. Louis Arsenal in which they train and guard, the religious character of his regiment, the qualifications of the officers, drilling on the guns, lack of supplies and poor quality supplies, the health of the men, etc. In November, having moved to Jefferson City, MO., Stafford receives his first taste of real wartime activity when alarms are sounded based on reports of the advance of Confederate Gen. Sterling Price and the battery is called to be ready for the defense of their post. In an interesting narrative on 26 November 1861, he describes how the men of his unit refused to take the Austrian muskets they were to be issued because the arms often would not fire, and so the battery was marched back to camp. "The refusal to take them is a very bold act on our part," he writes, "and it is uncertain what will be the result. I think it will at last satisfy the officers of this Post that there is grit in the Buckeye boys." On the 29th of that year, he sends his brother a detailed account of the battery, writing in small part: "It consists of six brass 6-pounders four of which are rifled and two smooth bores. The usual arrangement of what is called a 6-pounder battery consists of four 6-pounders guns and two 12-pounder howitzers.....The carriages and other equipment are all new I believe. A battery requires fourteen carriages vix. six for the pieces, six for the caissons, a battery wagon containing artificers tools, anda forge. Each of the fourteen requires six horses, making eighty-four. Then the five commissioned officers - eight sergeants and six artificers and two buglers are mounted on horseback...." This same letter includes a wonderfully detailed description of the noncommissioned officers in his unit.

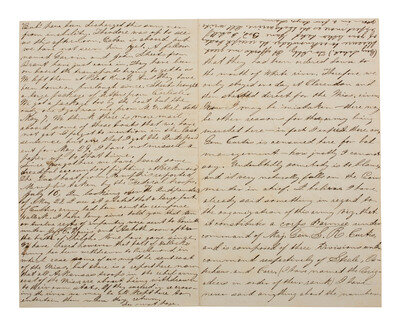

Early 1862 sees Stafford remain in Missouri. He writes on 24 March from "Bailey's Station, somewhere in Mo." regarding an "an interesting scene." "Some of the boys 'picked up' a negro yesterday (it did not take much persuasion) and just a little while ago two men (his master's son and neighbor) overtook us with the intention of taking back into slavery again. Of course they have 'produced satisfactory evidence' to the Captain that they are good Union men.... They cannot persuade 'John' that he'll be much better off if he goes back with them." Stafford's diary records these events as well, specifying that "John" was a runaway slave, and that the men looking for him "seemed to be afraid to try to force him when so many troops were present who sympathized with the slave." Throughout the overlapping portion of Stafford's diaries and letters (March - September 1862), his writings often complement one another in this way, referencing similar content but with the letters typically allowing for a more detailed explanation of occurrences referenced in the diary. Such is the case of action at Pitman's Ferry, recorded in the diary on 1 April 1862, and again in a letter home from near "Camp at Doniphan, Ripley Co. Mo." on April 2. Stafford relates here a detailed story about his fellow artillerist who was thrown from the caisson and then twice run over by it's wheels.

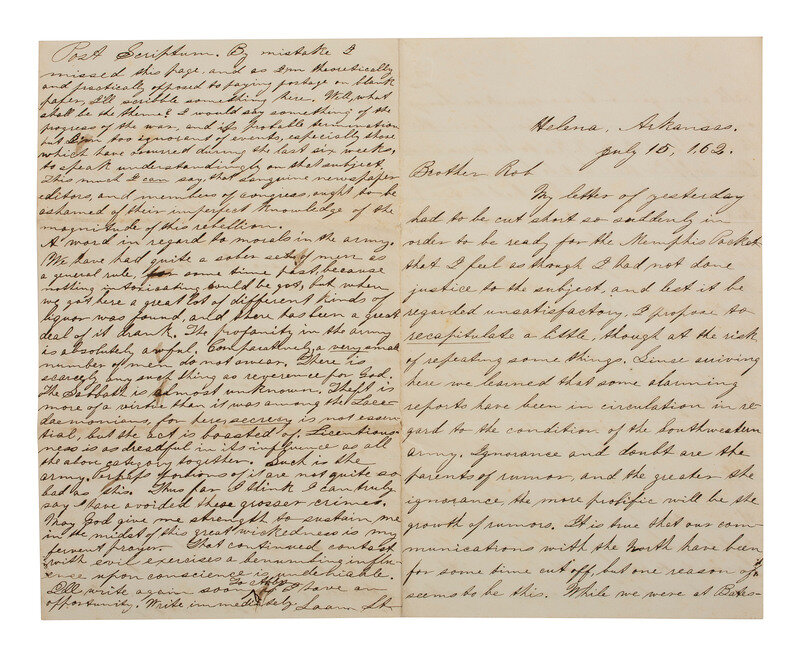

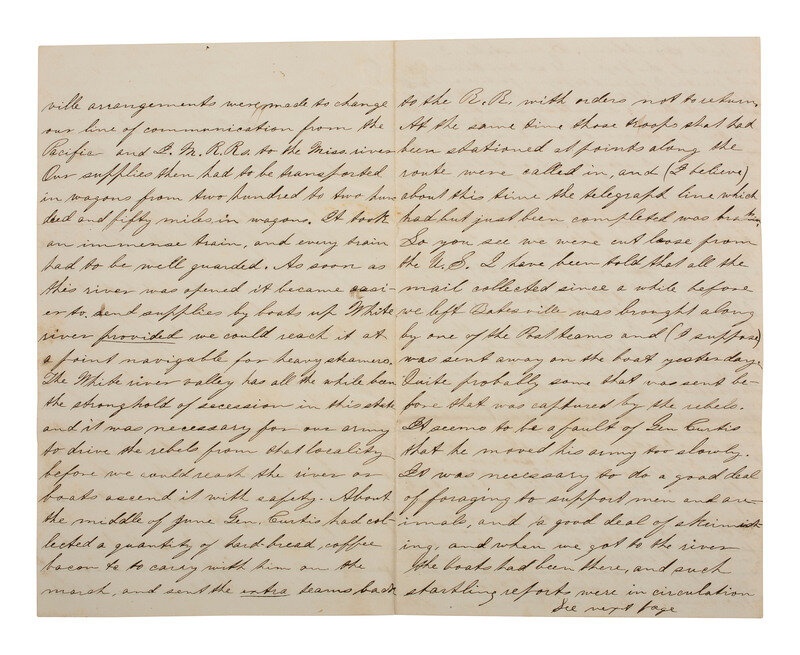

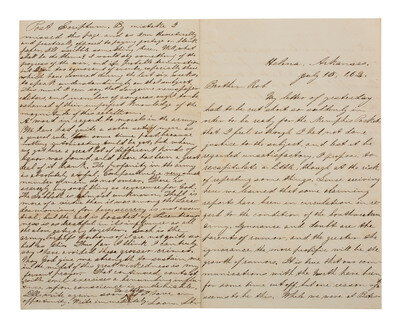

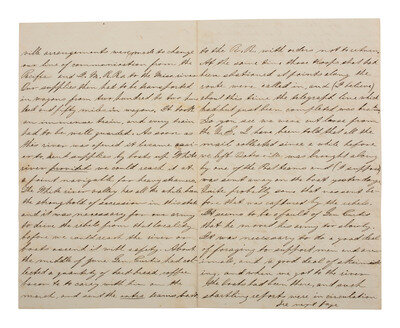

Moving with the battery deeper into the South there are only sporadic skirmishes, yet Stafford's narrative nonetheless remains engrossing with his meticulous details about the Battery's movements, the land, and its people. His diary entry of 9 April indicates a growing weariness with his circumstances: "Am getting tired of this mode of life. We are almost isolated from the rest of the world, and hear no news. The citizens (natives or butternuts) continue to come in and 'take the oath.' We have very little confidence in their oath." Reaching Arkansas, he writes home from Jacksonport on 5 May in praise of the country. "It is much better country though than any we have before seen. We have passed some very fine plantations. As we neared the river here the aristocratic element became more apparent - more slaves - better houses - larger farms &c." Later Stafford will recall enslaved persons coming to the Battery eager to serve as cooks, with the understanding that they are to be taken north as soon as the war is over. He writes too of his desire for immediate emancipation of all enslaved persons which he hopes might hasten the end of the war. On May 9 Stafford describes in a letter how the battery passes time when not marching, relaying an anecdote about an "independent foraging party" that "found (among other adventures) a house of considerable pretensions, that had been deserted." From this foraging adventure the soldiers returned with among other items, many books, "So our mess are busy today with literary pursuits...." Encounters with guerillas regularly plague Stafford and the 16th Battery. His diary records an attack on 28 June where "'bush-whackers' fired into our train from the cane-brake when our boys were off guard and killed a lieut. and three privates... Reinforcements soon arrived to our men and a sharp skirmish ensued in which (at least) five rebels were killed....Several of our men were wounded." The next day's diary entry notes that infantry and cavalry returned after scouring the country for the rebels, but "Artillery cannot be made very effectual against 'bush-whackers.'" Similar encounters with Confederate guerillas continue as Stafford and the 16th Battery endure a series of grueling marches through Arkansas. Particularly notable here is that, compared to his letters home, Stafford's diary is notably more candid in its representations of the danger and hardship he endured.

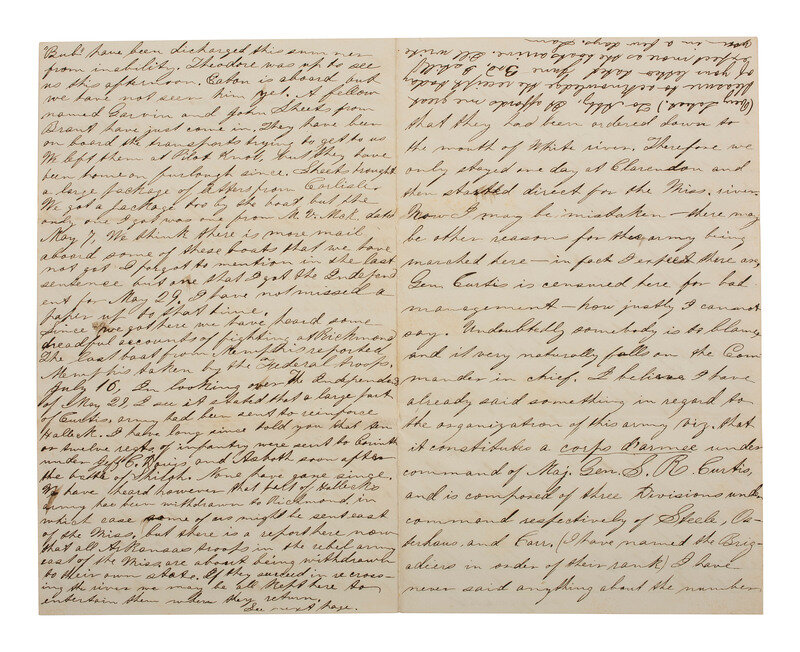

While the 13 July diary entry records a brief statement about arriving in Helena, Arkansas, a 9pp letter written on 15 July from Helena paints a vivid picture of the conflict as it was unfolding there, and is written in Stafford's characteristically descriptive way: "Helena was the place of residence of the rebel Gen. Hindman, and his splendid mansion is now the Head Quarters of Gen. Steele. Gen. Pillow owns several fine plantations near the town, and he himself lived four or five miles south of it. Yesterday afternoon three buildings were burned in the town and more would have shared the same fate but for the efforts of Union soldiers to extinguish the fire. Of course the blame was expected to rest on Union soldiers, but fortunately, a man was caught in the very act of firing a building, and on being arrested, confessed himself to be an emissary from Gen Hindman, sent to burn the town. I presume there is hardly a state in the Union in which the secession element is more intense - in which there is more of the barbarism of the South than in Arkansas. All the way down the White river valley, the cotton had been hauled out from the gins and burned. Scarcely any men were to be seen and many of the houses were totally deserted. They had even hid their bacon and part of their corn in the woods to prevent us from getting it, and in some instances resorted to various tricks to prevent us from getting any water out of the wells on the road. We have drank a great deal of water from swamps that you would consider entirely unfit for horses or cattle. It is not strange that Federal officers found it difficult to prevent the destruction of property by their soldiers. Some has been destroyed - some buildings burned &c, but great efforts have been made to prevent it."

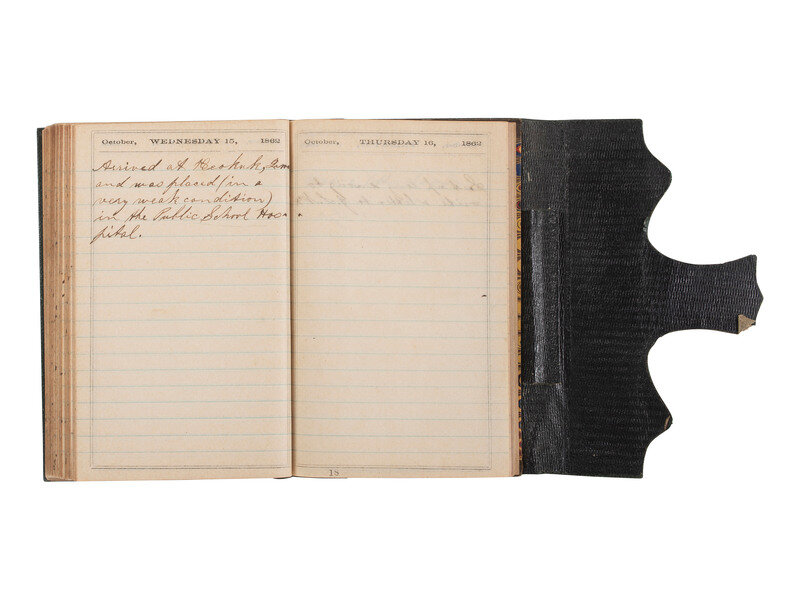

Diary entries in August and September 1862 indicate that Stafford's health is diminishing while on extended duty at Helena. Stafford, as with many men in his company, already suffered from the ill effects of long marches, the elements, and poor sustenance. Poor sanitation at the encampment in Helena seems to worsen the health of many men. He writes in his diary on 26 September "Company in deplorable state of inefficiency. Idea of taking the field under such circumstances, rather a gloomy one." His last letter home has a postscript dated September 27. One week later Stafford's diary records that he was carried to a U.S. Hospital boat. On October 15th, he writes: "Arrived at Keokuk, Iowa and was placed (in a very weak condition) in the Public School Hospital." His last diary entry was made on 8 November, 1862. "Was confined at home by dangerous and protracted sickness during the remainder of the year."

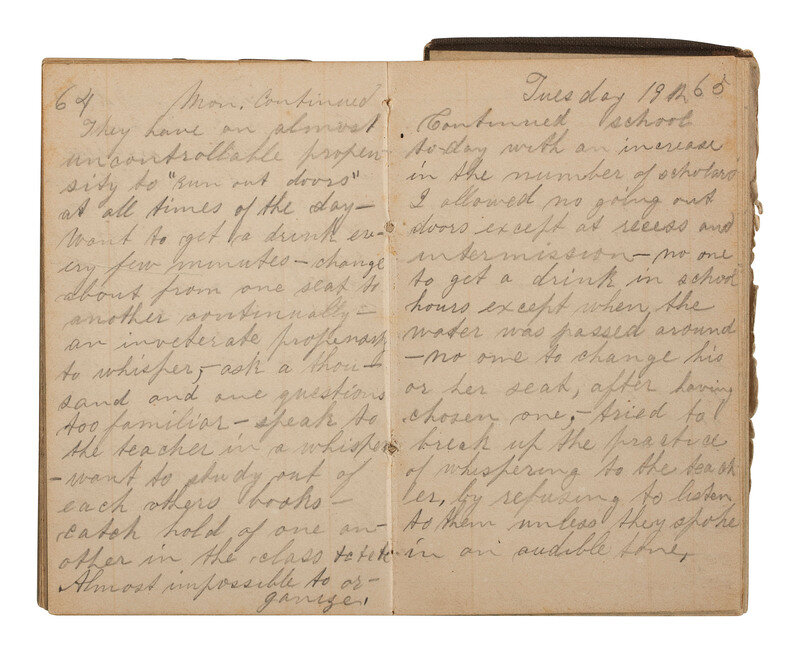

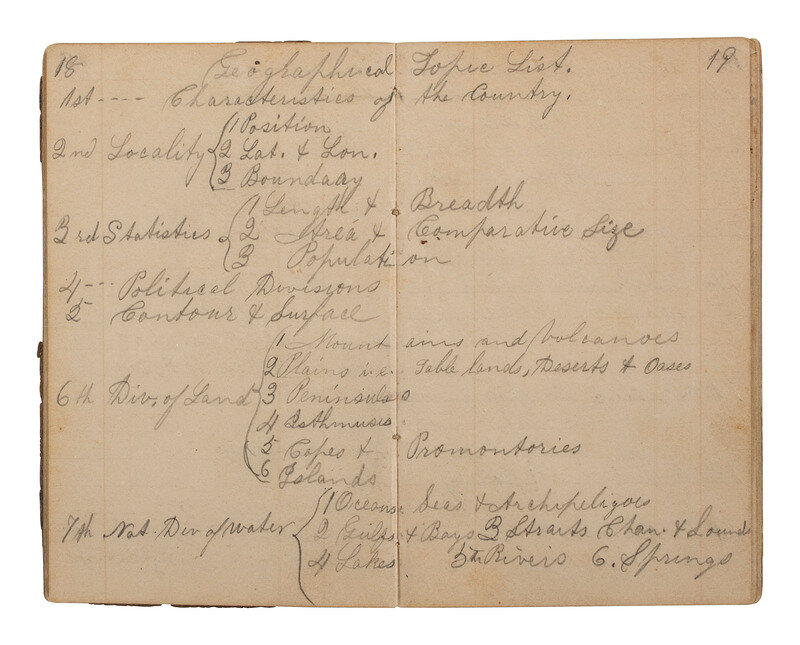

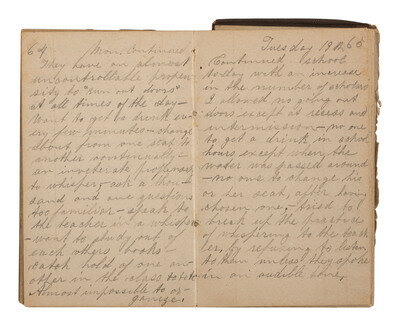

[With:] Samuel Stafford's pre-war diary, spanning 1858-1859, in which he documents his training to become a school teacher, and records his lectures and daily occurrences in the classroom. Additional content details a trip via Cincinnati into Kentucky where he engages in the "tree business." Stafford writes of his travels there and throughout the state, noting the places and people he encounters, including enslaved African Americans. 113pp , 3 x 5 in. -- Stafford's 4 pre-war letters home, spanning March 1859 - May 1859, also written from Kentucky while he was selling trees, with wonderfully descriptive details of his work and travel, as well as his opinions on Kentucky society and culture. -- 2 war-date letters written to members of the Stafford family by Gordon C. Kennedy, a fellow soldier in the Ohio 16th Battery, and 1 letter written to the Stafford family by William S. McKinney, a cousin who also served in the Ohio 16th Battery. -- 1 letter from the Rev. Henry B. Belmer to Stafford's brother, 24 October 1924, recalling Stafford's service in the 16th Battery in which Belmer also served.

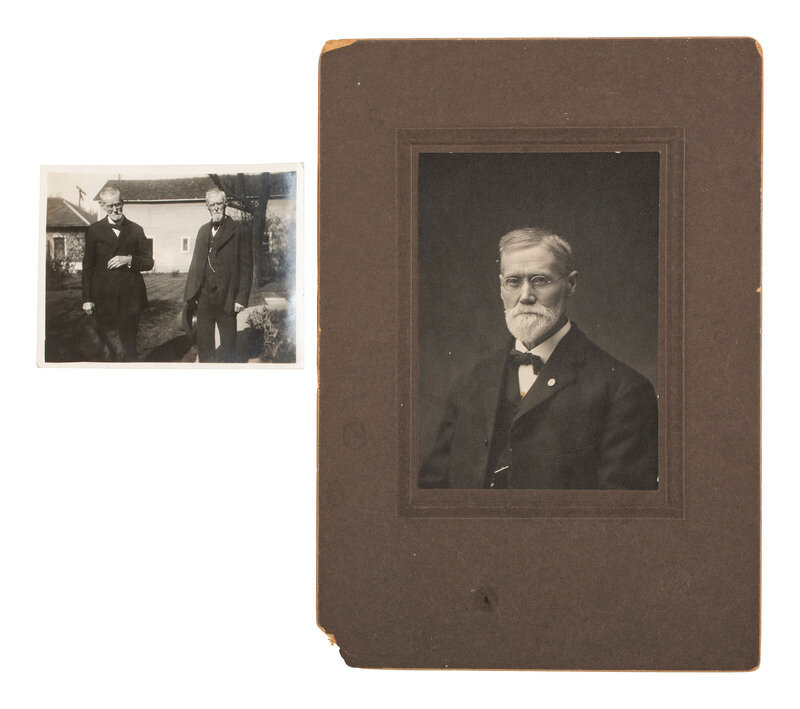

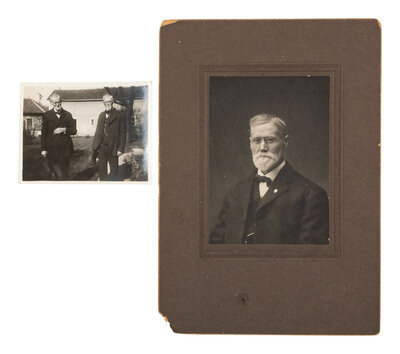

[Also with:] Two photographs of Stafford, one an undated seated portrait measuring 7 x 10 in. with mat, and the other an undated 4 1/4 x 3 in. snapshot identified on verso as Stafford and James L. McKinney. -- STAFFORD, Horace W. Genealogy and Biographical Sketch of The Stafford Families of Ohio and Indiana. Springfield, Ohio. 1 March 1927. Inscribed on title page "Miss Nell J. Stafford. July 12th 1927." 143pp.

Samuel McKinney Stafford was born on August 6th, 1837, in a log cabin in Pike Township, Clark County, Ohio on the site first settled by his grandfather, George Stafford, Sr. He began teaching at the age of nineteen and continued to do so until President Lincoln issued his call for three thousand volunteers. HDS indicates that Stafford enlisted as a 24-year old corporal on 8/20/1861 in the 16th Ohio Battery (16th Ohio Light Artillery) under Captain James Anderson Mitchell. After sixteen months of service and in increasingly poor health, he was sent to the Government Hospital at Keokuk, Iowa, where he remained until November, 1862, when he was discharged for disability. After the war, Stafford returned to farming and teaching, living out the remainder of his days in Ohio until his death in 1922.

This lot is located in Cincinnati.

Condition Report

Auction Specialist