Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

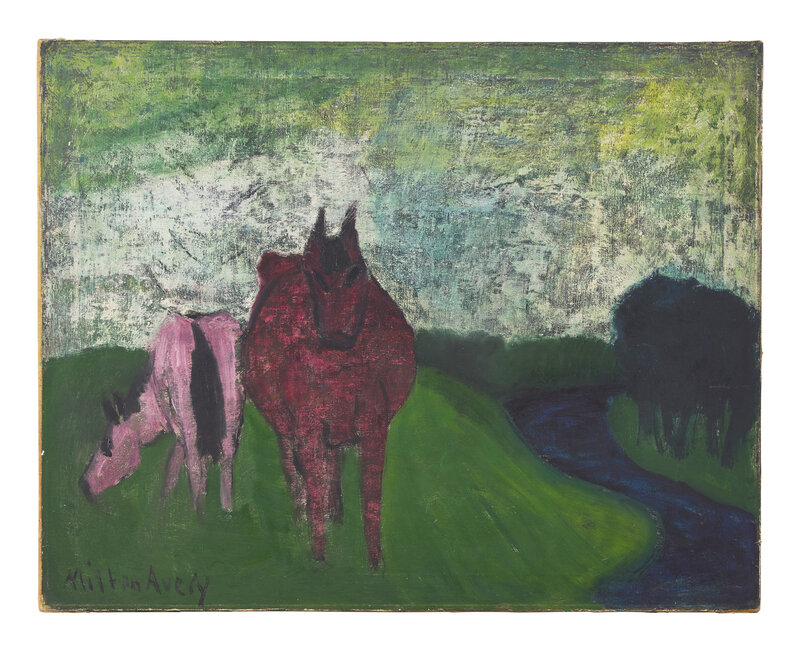

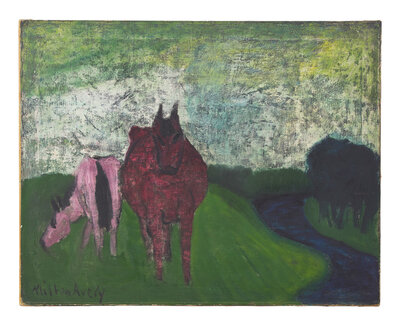

Lot 159

Milton Avery

(American, 1885-1965)

Horses in Spring, c. 1936

Sale 2105 - American Art and Pennsylvania Impressionists

Dec 8, 2024

2:00PM ET

Live / Philadelphia

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$100,000 -

150,000

Price Realized

$76,200

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Milton Avery

(American, 1885-1965)

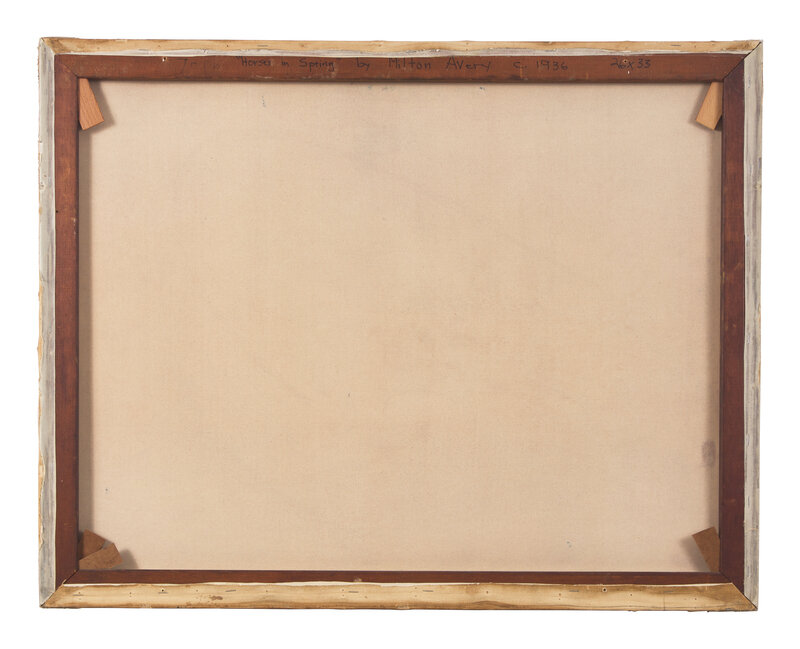

Horses in Spring, c. 1936

oil on canvas

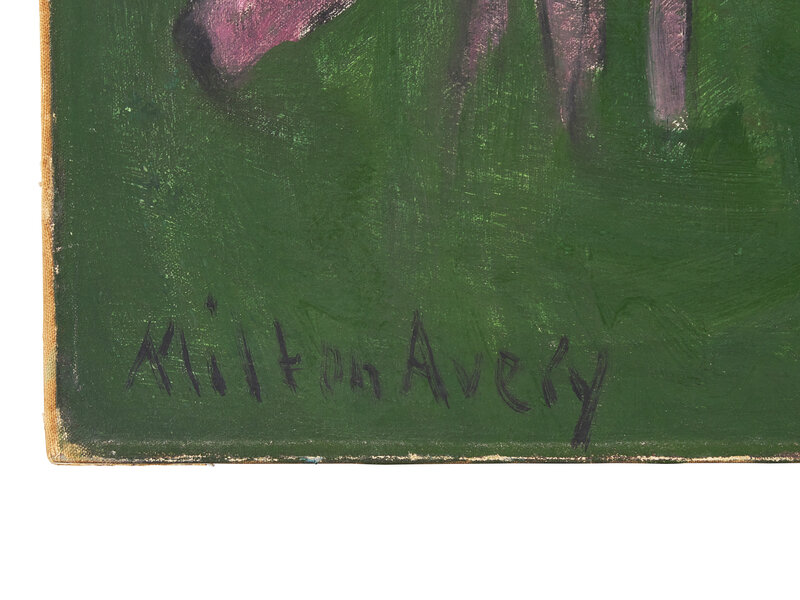

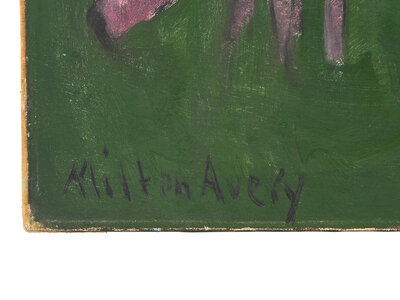

signed Milton Avery (lower left)

26 x 33 in.

The Collection of Dr. Julian Katz and Dr. Sheila Moriber Katz, Gladwyne, Pennsylvania.

This lot is accompanied by a letter of opinion from The Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation.

Exhibited:

Naples, Florida, Harmon-Meek Gallery, Milton Avery's "Birds & Beasts," 1931-1936, March 24 - April 15, 1986 (and traveling).

Literature:

Frank Getlein, Milton Avery's "Birds & Beasts," 1931-1936, Harmon-Meek Gallery, Naples Florida, 1986, illustrated p. 4.

Lot Essay:

One of the distinctive features of modernism is the emphasis on an artwork’s physicality, from support and medium to technique. This tenet was core to Milton Avery’s aesthetic, who viewed the composition of his paintings as an effort in organizing forms, lines, and colors. On the surface of the canvas, which strictly delineates spatial borders, the image becomes an impeccable assemblage, where visual and textural elements tie the artist’s vision together.

This calculated structuring implies that the objects represented in the painting are modified, even simplified and nearly abstracted, to fit into the intended design. This visual economy typically favors patches of color, interlocking shapes, and marked spatial delimitation of objects. Roger Fry, in his seminal book Transformations (1927), speaks of “integral plastic expression,” referring precisely to this subjugation of meaning to the physical elements of the painting—the palette, the contours—whereby the work as object becomes its own subject. In Horses in Spring, the surface is quite visibly uneven; physicality is manifested through the rather soft, though unmistakable, separation between forms and their corresponding colors as well as the conspicuous brushwork and the rugged patterns it produces.

Yet Avery’s aesthetic is not as straightforward as it seems. In addition to the material foundation that defines Horses in Spring, the painting’s very physicality is ironically what points to its other, more loosely defined, less tangible, dimension. The color irregularities as well as the subtle blending of hues, especially noticeable in the background and sky, drape the composition in a mesmerizing haze. It is this rather fussy appearance that signals the poetic element inherent to Avery’s practice. While the painting’s physicality is overwhelming, from it radiates an airier plenitude, which renders the solid surface of the canvas pervious to a profound affinity with the natural world.

The process of simplification described above leads to the capture of a moment or vision, an essential gesture in which the artist’s, and in turn the viewer’s, piercing eye meets the direct gaze of the horse, as if engaging in a dialogue with nature. As Clement Greenberg stated in 1957, “one does not manipulate a subject, one meets it.” When Avery simplifies the natural world around him, he does not merely manipulate it to make it readily accessible; he distills its potential depth. He provides an invitation to look and feel, not an explicit and all-encompassing account. In his final tribute to Avery, Mark Rothko aptly summed up this core dimension of Avery’s aesthetic—where the physical is tightly intertwined with the metaphysical—as “that inevitability where the poetry penetrated every pore of the canvas to the very last touch of the brush.”