Lot 185

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

(Italian, 1720-1778)

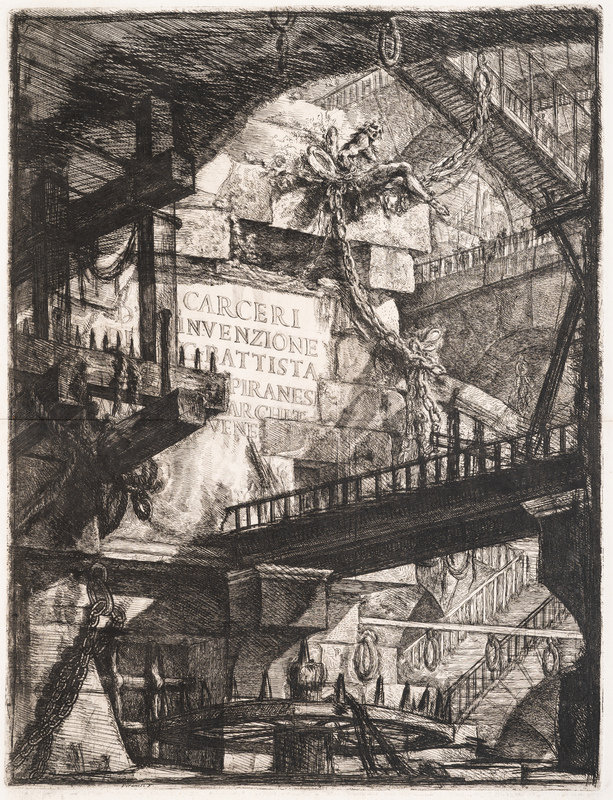

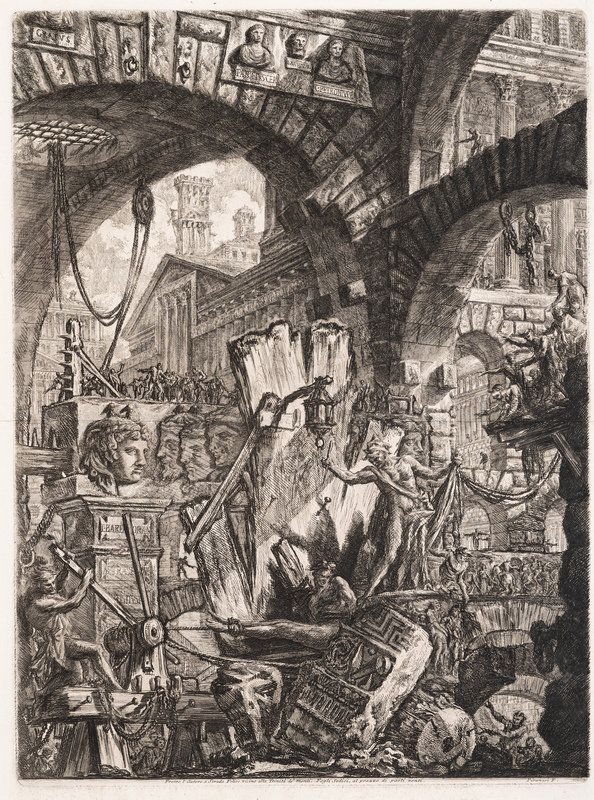

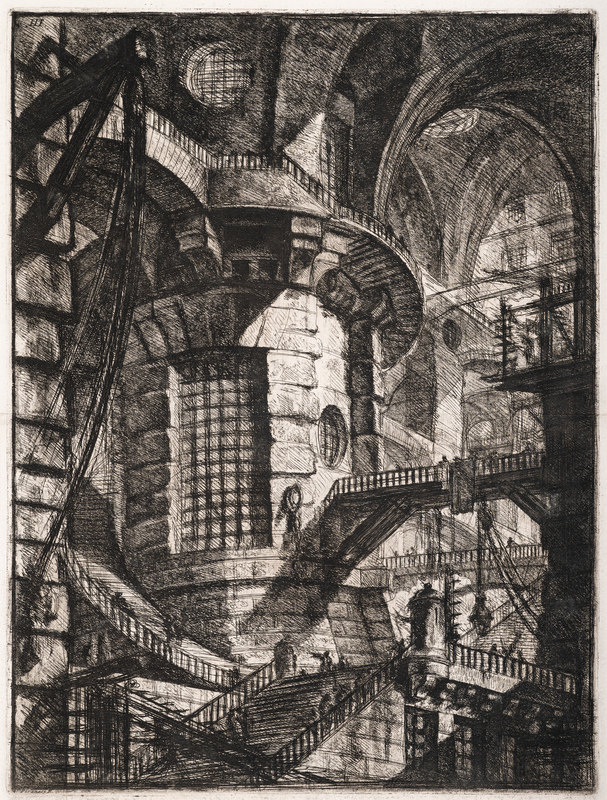

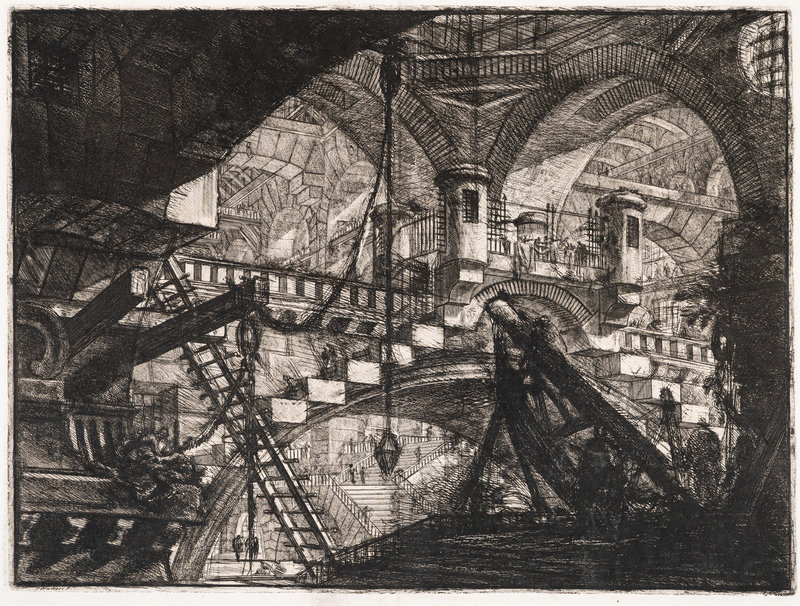

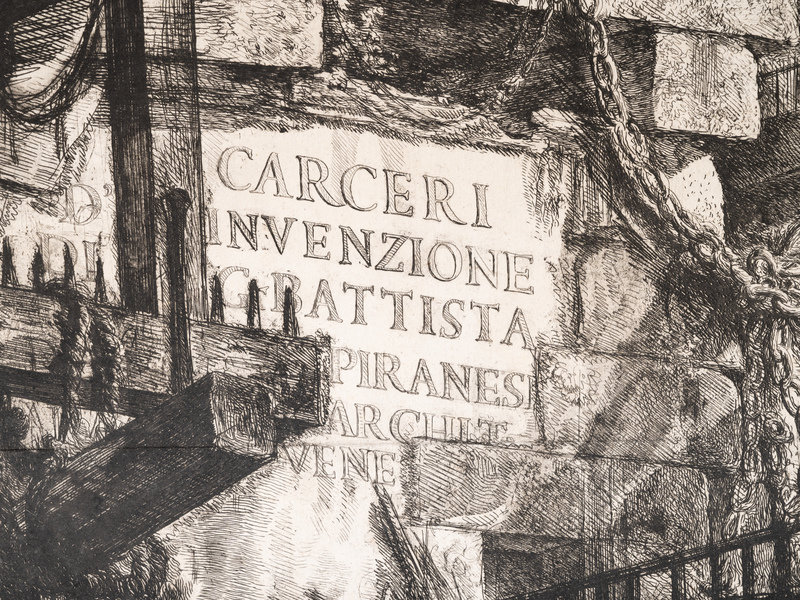

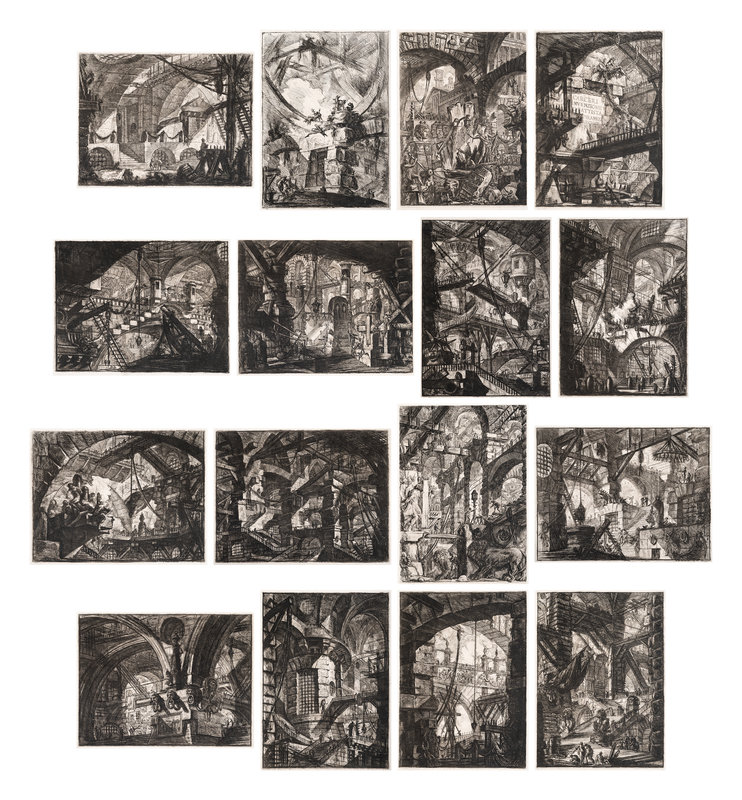

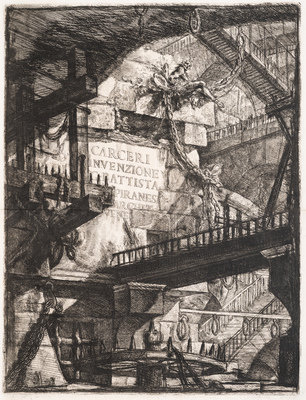

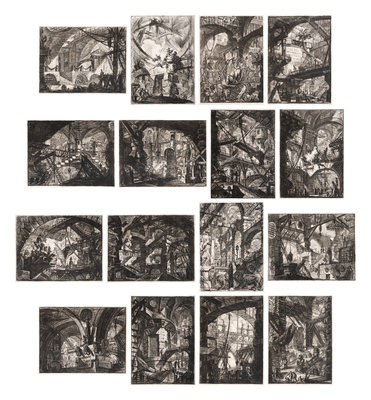

Carceri d'Invenzione (the complete set of 16), 1761

Sale 908 - Prints and Multiples

Sep 29, 2021

10:00AM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$20,000 -

30,000

Price Realized

$46,875

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

(Italian, 1720-1778)

Carceri d'Invenzione (the complete set of 16), 1761

etchings with engraving

21 1/2 x 16 3/8 inches (each).

Property from the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

Literature:

Hind 1-16

Provenance:

Weyhe Gallery, New York

Collection of Dr. Rudolph Langer, Madison, Wisconsin

Bequest from the above to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

The Influence of Piranesi’s Carceri d'Invenzione

Hind 1-16

Provenance:

Weyhe Gallery, New York

Collection of Dr. Rudolph Langer, Madison, Wisconsin

Bequest from the above to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

The Influence of Piranesi’s Carceri d'Invenzione

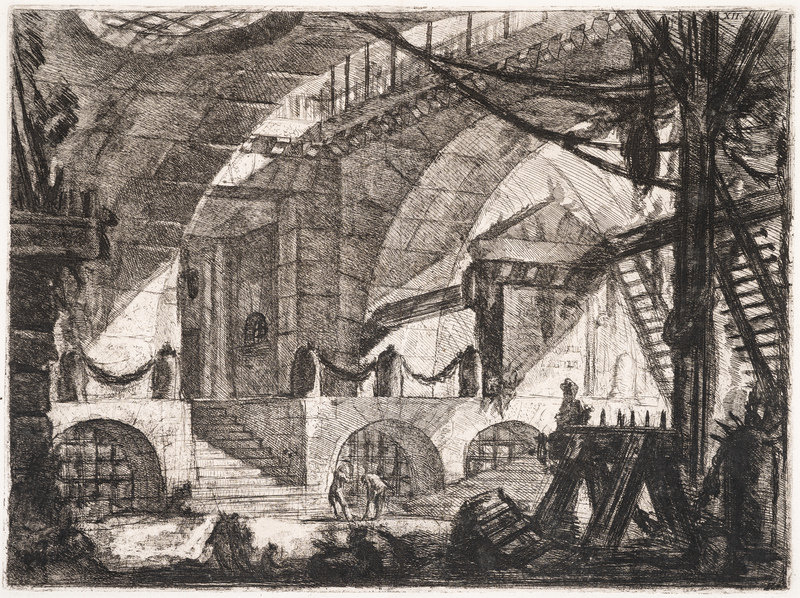

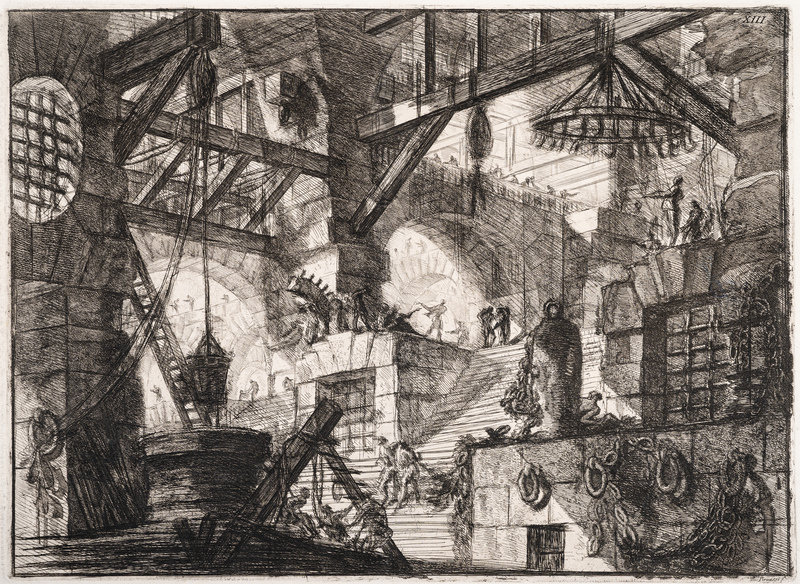

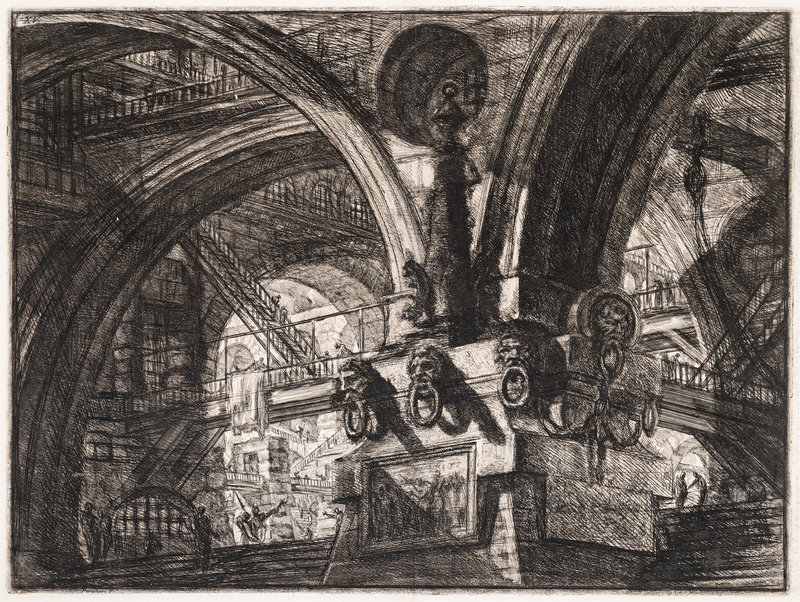

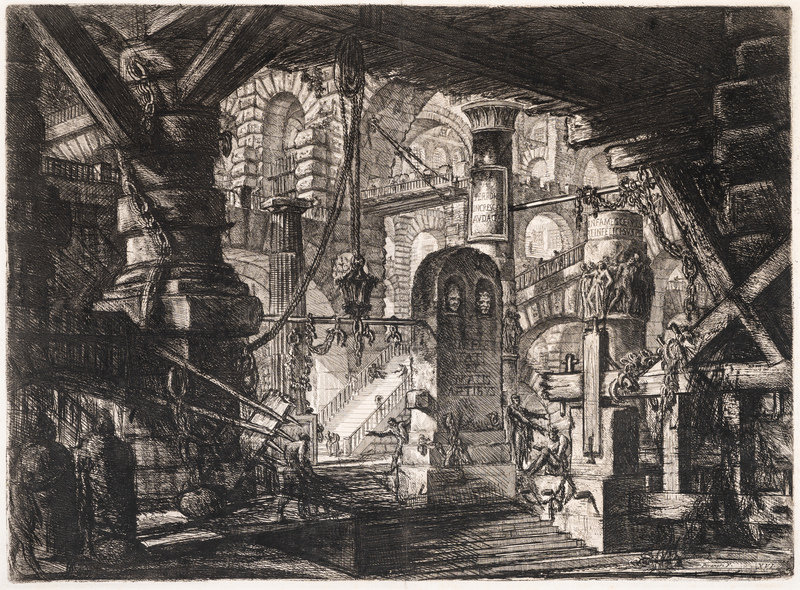

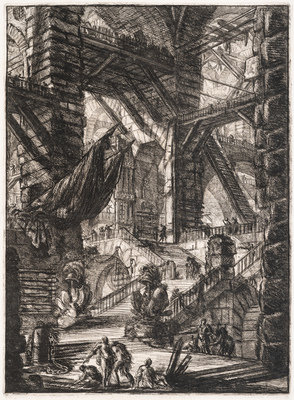

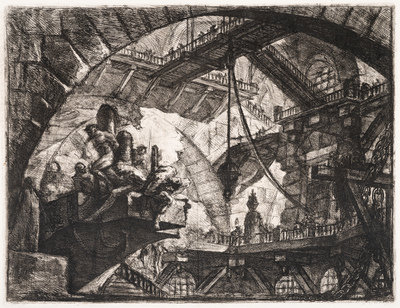

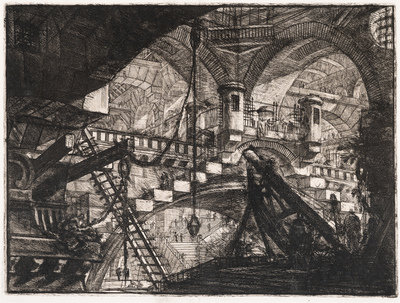

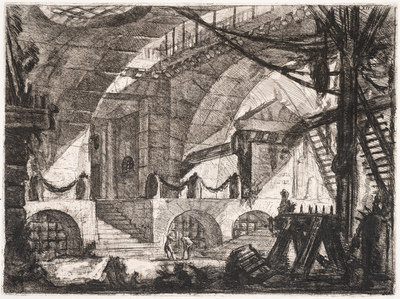

The Venetian artist and architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) published two editions of his series of imaginary prisons, Carceri d'Invenzione (Prisons of Invention). The first set of etchings with engraving was published as a group of 14 between 1749 and 1750. Hindman is pleased to offer a set of the second edition which Piranesi published in 1761 after significantly reworking each plate and introducing two more plates for a total of 16 (Lot 185).

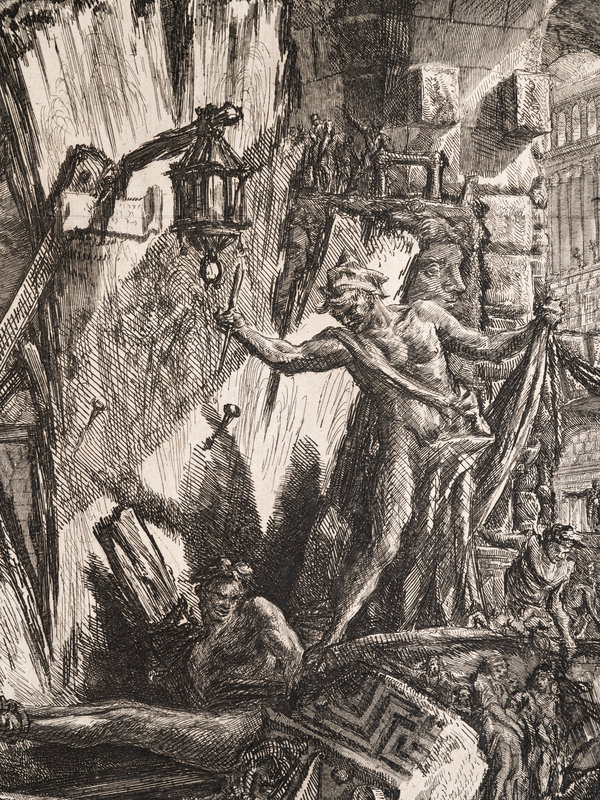

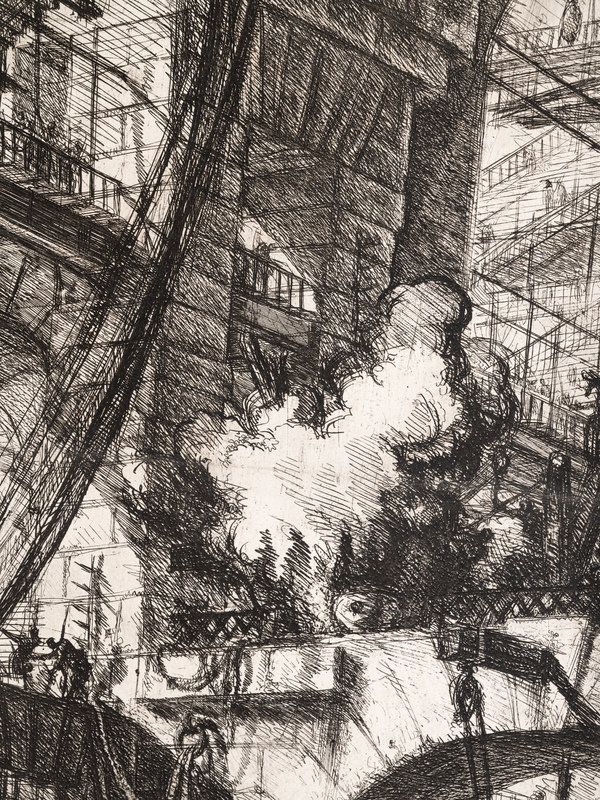

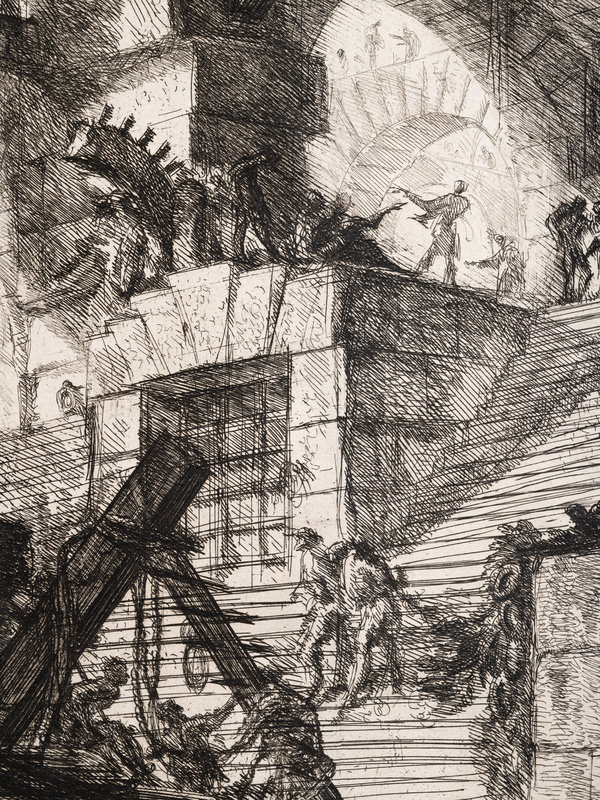

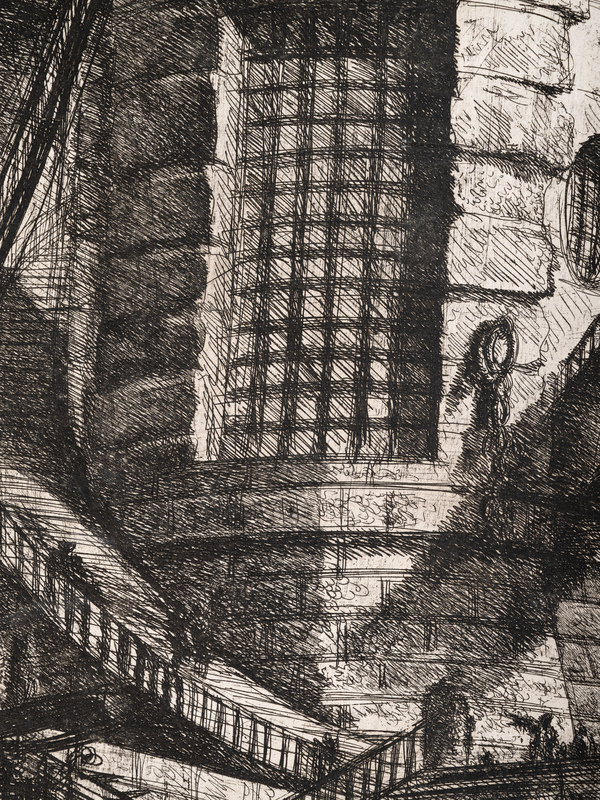

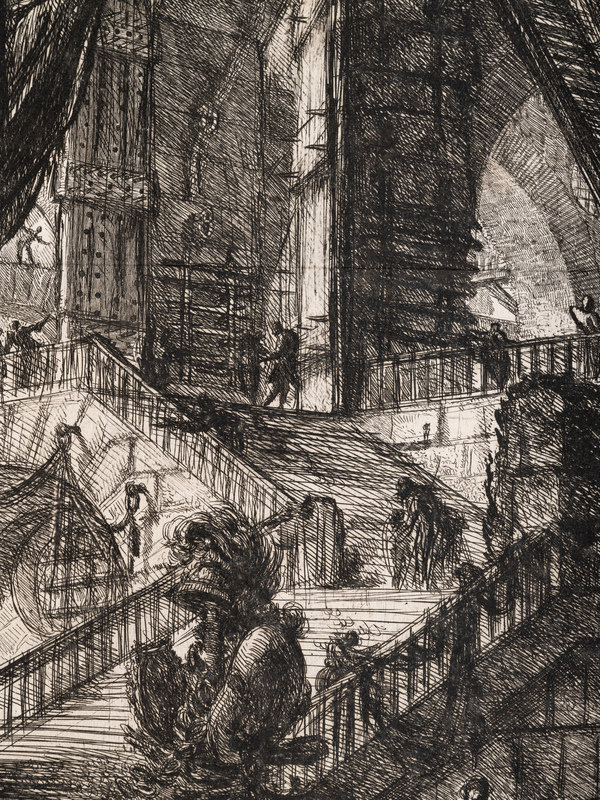

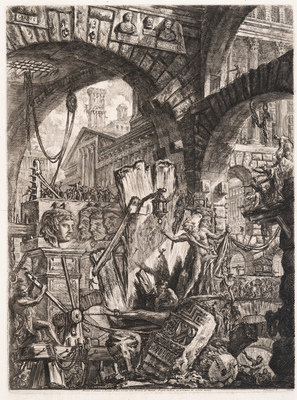

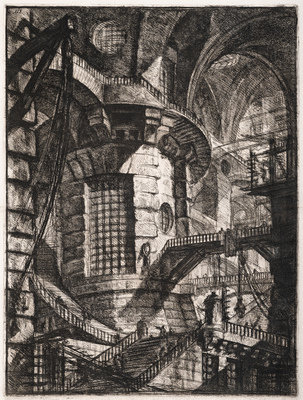

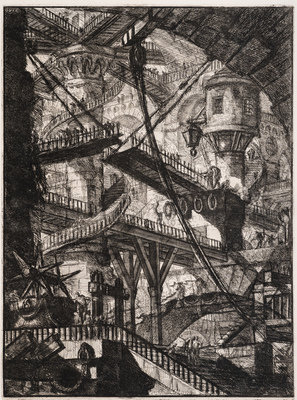

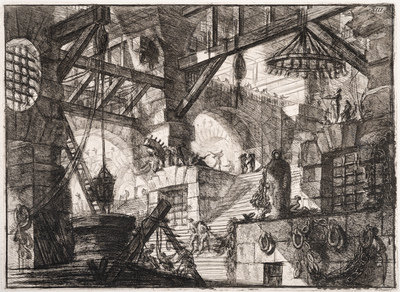

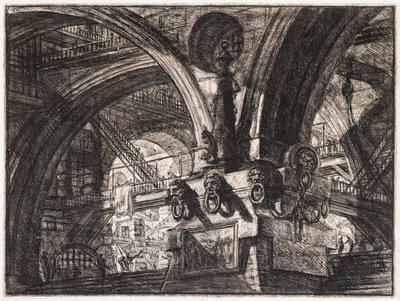

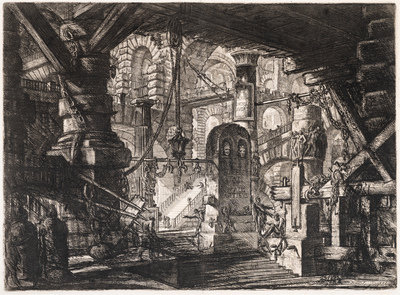

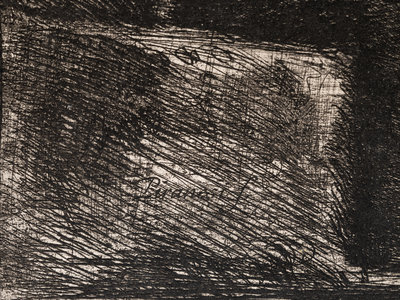

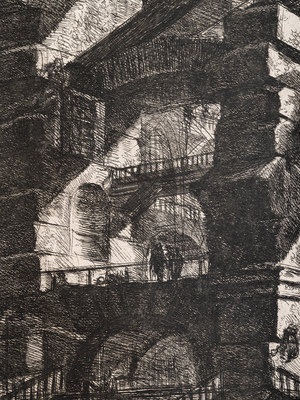

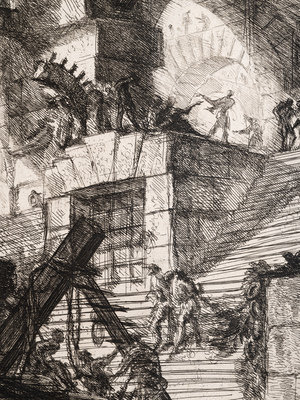

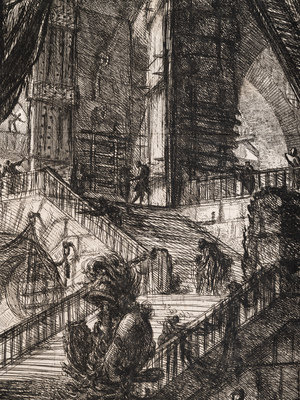

Belonging to the artistic genre of the capriccio or architectural fantasy, the Carceri became an enduring influence for art history, particularly in the twentieth century. Piranesi’s scenes within the Carceri are foreboding. The architectural spaces are unnaturally high, with diminutive figures emphasizing the scale. Background features seem to recess with no discernable pattern that is nonetheless stable and believable.[i] The source of light in each is unseen, but backlit from a high diagonal. Different architectural elements are juxtaposed—arches, bridges, obelisks, etc.—in both vertical and horizontal compositions that lead the eye up multi-level structures, inclusive of cranes, gallows, and chains.[ii] The second edition of 1761 presented here includes much more shading, emphasizing the dark, ominous environment. The beginning plates of the series, including the title page, are more lit or else take place outdoors, where it is easier to see terrible punishments or other unsavory aspects of the prisons, as in the second plate prominently displaying a man being tortured on a rack. As the series progresses through the plates, the palette becomes darker as the scenes are shifted to more interior views, such as in the eighth plate, The Staircase with Trophies, where it is so dark that it is no longer possible to make out individual facial expressions. To create these bold effects, Piranesi drew upon Venetian artistic traditions, particularly his background developing stage sets, such as for dramatic contemporary operas, and capricci.

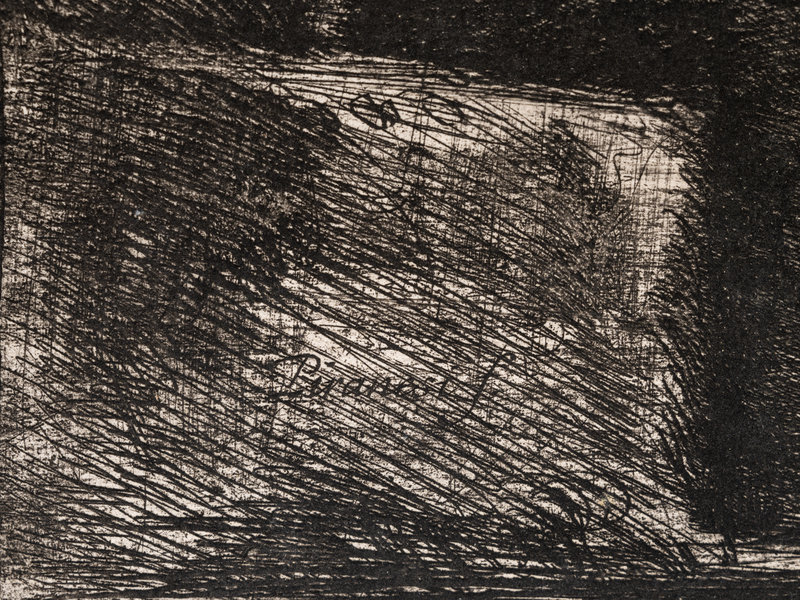

A capriccio is an artistic genre of invention for invention’s sake—architectural fantasies, pastiches of seemingly unrelated themes, “a dreamlike vision arising out of the free play of the imagination.”[iii] Though present throughout the Renaissance and beyond, capricci became particularly popular through the artwork of Piranesi’s contemporaries, the Tiepolo family in Venice. As with early modern printmaking more generally, these prints were designed to strongly engage the viewer’s attention and were meant to be studied closely, which, due to the capricci’s tendency to “confound the savviest of interpreters,” served as a particularly bold illustration of the artist’s skill.[iv] For example, in the more-heavily shaded version of the 1761 Carceri, the great variation of mark-making throughout the series emphasizes Piranesi’s printmaking ability in addition to his knowledge of architecture: lines varying in length, width, and direction, areas of stippling, and patterns of short, squiggly lines are deployed throughout. The heavy shading obscures figures and details within the deepest recessions of shadow, but the variation of line is so skillful that, even in areas of black, it is possible to define different forms and textures, allowing the viewer the game of teasing out figures and details only after close examination. In some, even Piranesi’s signature is hidden under a laying of heavy etching. This mixture of fantasy and skill would influence many future printmakers, such as Goya in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but Piranesi’s legacy can be particularly seen in twentieth-century printmakers, such as MC Escher, Dalí, Picasso, and others.

The Carceri’s influence on MC Escher is well-documented. In 1935, Escher hung several prints by Piranesi up in his studio in Château-d’Oex, Switzerland.[v] Similarly, Giorgio di Chirico not only examined Piranesi’s works, but also his writings as sources of inspiration.[vi] Recently, in October 2020, the National Museum—Architecture in Norway hosted an exhibition titled “Piranesi and the modern age,” in honor of the 300th year anniversary of Piranesi’s birth in 1720, further examining his influence on such diverse subjects as the science fiction genre and Walt Disney.[vii] Unsurprisingly, Piranesi is also considered a major precursor of Surrealism, so much so that Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, included three prints of Piranesi’s, all from the Carceri, in the 1936 exhibition Fantastic art, dada, surrealism[viii]. One of the impressions from the first edition was loaned by the Weyhe Gallery, New York, where Hindman’s set of the Carceri can also be traced.[ix]

Dali was unequivocally directly inspired by the Carceri. In his personal collection, he had 12 prints from a facsimile version of the Carceri that the Club International de Bibliophilie of Monaco published in 1961; these prints remain permanently on display at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Dalí’s hometown of Figueres, Spain.[x] These influences can be seen in Lot 74, Dalí’s Memories of Surrealism series, published 10 years later in 1971. In a series that is both self-referential and largely references the western art historical canon through borrowing images such as the Mona Lisa, ancient sculpture, and artwork by Georges de La Tour, these prints share with the Carceri a juxtaposition of figures and architectural elements of different scales in fantastical backgrounds. One example in particular is indebted to the Carceri: where an elephant on long, spindly legs crosses the indeterminant landscape. The elephant’s body is bisected to show itself to be a multi-level architectural marvel: winding staircases, columns, and brickwork shaded to reveal a strange and impossible interior inside the elephant, while its legs span to create an arch, so common among Piranesi’s scenes. The whole elephant is defined in black and white, mirroring Piranesi’s etching, while faceless figures populate the landscape in greatly differing scales, highlighting the monumentality of the elephant’s form. Dalí is able to harness the spirit of the genre of the capriccio through his pastiche of unrelated elements deployed in an inventive way that requires careful examination for the viewer to attempt to unravel.

The Carceri highlights Piranesi’s inventiveness, architectural knowledge, and artistic ability through its presentation of architectural fantasy meant to be closely examined and admired by the viewer. These impressive capricci strongly influenced later artists, especially in the twentieth century. This influence is seen literally in the work of Escher and Dali and are considered one of the major contributors to the foundation of Surrealism. This artistic genre of using elements of pastiche and invention to emphasize an artist’s mastery of material and artistic creation has remained central to the art historical canon as well as printmaking as a medium.

Works Cited

Barr, Jr., Alfred H., ed. Fantastic art, dada, surrealism. New York: MOMA, 1936.

“Carceri d’Invenzione, Les Prisons Imaginaires de Gian-Battista Piranesi. 12 prints of the facsimilie edition published by the Club International de Bibliophilie de Monaco el 1961.” Fundació Gala - Salvador Dalí. Accessed August 16, 2021.

Kersten, Erik, ed. “Giovanni Battista Piranesi.” Escher in Het Paleis. November 14, 2020. Accessed. August 17, 2020.

Parshall, Peter. “Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo: The Pastiche as Capriccio.” Print Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 3 (September, 2011): 327-330.

Notes:

[i] Sarah Vowles, Piranesi drawings: visions of antiquity (London: British Museum, 2020), 9.Piranesi was so skillful at realistically exaggerating architectural perspective that when visited Rome, Goethe, after studying Piranesi’s etchings, thought its monuments smaller than expected and thus disappointing.

[ii] Ibid., 68.

[iii] Peter Parshall, “Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo: The Pastiche as Capriccio.” Print Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 3 (September, 2011): 327.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Erik Kersten, ed., “Giovanni Battista Piranesi.” Escher in Het Paleis, November 14, 2020, accessed August 17, 2020,

[vi] Bart Verschaffel, “The trophy figure in the work of Giorgio De Chirico (and Piranesi),” The Journal of Architecture 15 no. 3, 351.

[vii] “Piranesi and the modern age,” National Museum—Architecture, accessed August 17, 2021.

[viii] Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Fantastic art, dada, surrealism (New York: MOMA, 1936), 203-204.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] “Carceri d’Invenzione, Les Prisons Imaginaires de Gian-Battista Piranesi. 12 prints of the facsimilie edition published by the Club International de Bibliophilie de Monaco el 1961,” Fundació Gala - Salvador Dalí, acessed August 16, 2021.

[i] Sarah Vowles, Piranesi drawings: visions of antiquity (London: British Museum, 2020), 9.Piranesi was so skillful at realistically exaggerating architectural perspective that when visited Rome, Goethe, after studying Piranesi’s etchings, thought its monuments smaller than expected and thus disappointing.

[ii] Ibid., 68.

[iii] Peter Parshall, “Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo: The Pastiche as Capriccio.” Print Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 3 (September, 2011): 327.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Erik Kersten, ed., “Giovanni Battista Piranesi.” Escher in Het Paleis, November 14, 2020, accessed August 17, 2020,

[vi] Bart Verschaffel, “The trophy figure in the work of Giorgio De Chirico (and Piranesi),” The Journal of Architecture 15 no. 3, 351.

[vii] “Piranesi and the modern age,” National Museum—Architecture, accessed August 17, 2021.

[viii] Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Fantastic art, dada, surrealism (New York: MOMA, 1936), 203-204.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] “Carceri d’Invenzione, Les Prisons Imaginaires de Gian-Battista Piranesi. 12 prints of the facsimilie edition published by the Club International de Bibliophilie de Monaco el 1961,” Fundació Gala - Salvador Dalí, acessed August 16, 2021.

Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialists