American or English School

Sale 1060 - American Furniture, Folk & Decorative Arts

Lots 1001-1304

Sep 14, 2022

10:00AM ET

Lots 1305-1582

Sep 15, 2022

10:00AM ET

Live / Cincinnati

Estimate

$30,000 -

$50,000

Sold for $21,250

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

American or English School

Circa 1830

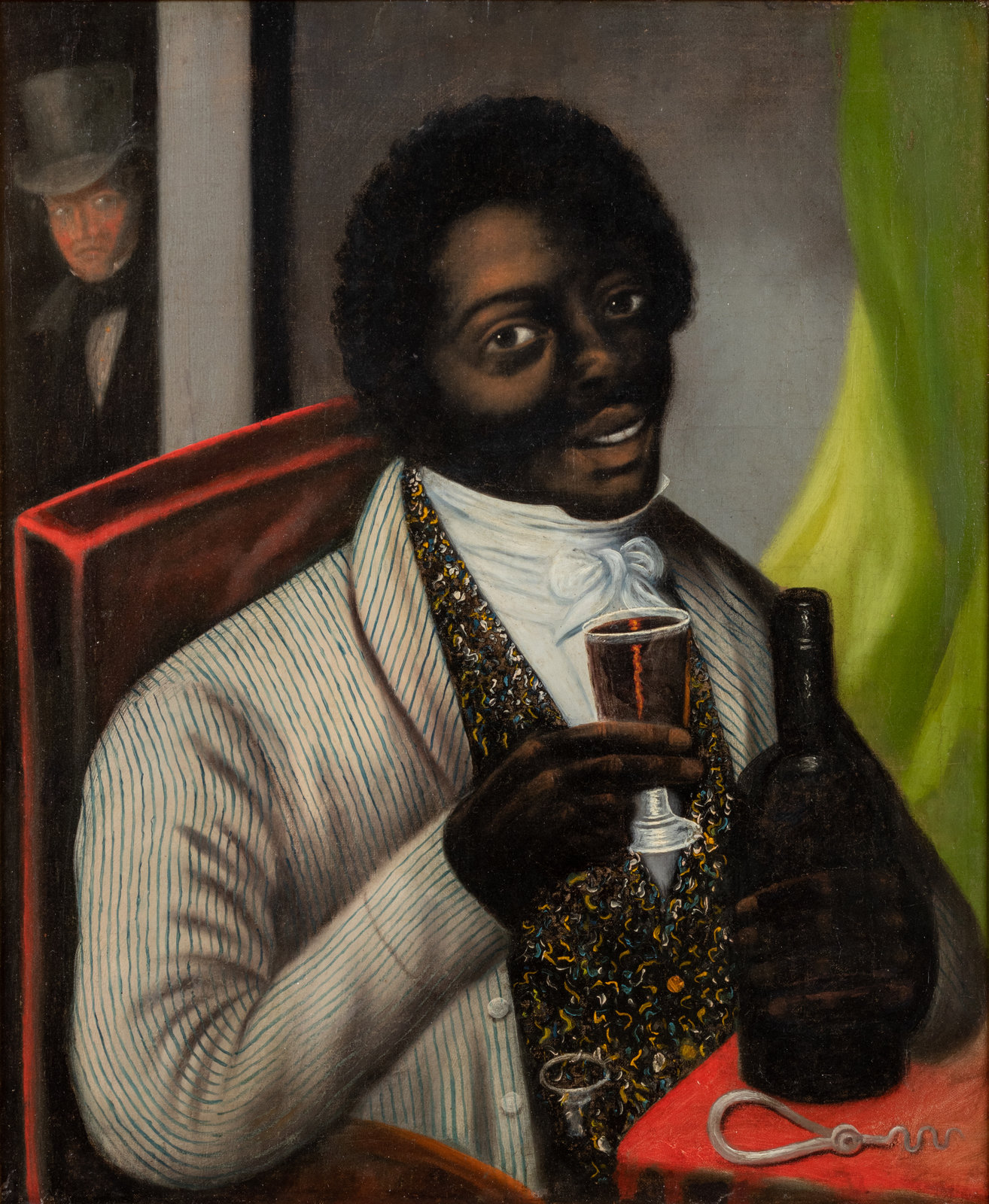

Portrait of Ira Aldridge as Mungo in 'The Padlock'

oil on canvas

24 x 20 inches.

oil on canvas

24 x 20 inches.

Lot Essay:

Ira Frederick Aldridge (1807-1867) was an American actor, playwright, theater manager and abolitionist whose relative absence from the annals of American history belies his stature as an icon of African American theater and one of the most famous and groundbreaking performers of the 19th century. Born in Manhattan in 1807 to Daniel and Luranah Aldridge, he received a formal education from African Free School No. 2, established by the New York Manumission Society for the children of slaves and freed Black residents alike.[1] Although his father, Daniel, who worked as a straw vendor and lay preacher, hoped that his son would follow in his stead and pursue religious ministry, Aldridge was drawn to the stage from an early age.[2] He gained early acting experience through roles with the African Theatre, later the African Grove Theatre, the first African American theater company in the United States. The backlash to the company’s all-Black productions of plays like Othello and Richard III was almost immediate in the acutely racist milieu of early nineteenth century America, and white neighbors’ complaints, police raids and eruptions of retaliatory violence convinced Aldridge that he would need to leave America if he was to pursue a career as a professional actor.[3]

In 1824 at the age of 17, he set off for Liverpool, earning his passage as a ship’s steward. James Joseph Sheahan, an actor and close friend who toured with Aldridge for years, recounted that while Aldridge worked as a steward he “managed to scrape an acquaintance with the late James Wallack, then manager of a theater at New York, and when that gentleman resolved upon returning to England, he conceived the idea of introducing young Aldridge to his fellow country people, and thus making money by him.” Philip A. Bell, one of Aldridge’s classmates at the African Free School, remembered slightly different circumstances surrounding their introduction: “…while acting [at the African Grove Theatre, Aldridge] became acquainted with Mr. Wallack, who, seeing talent in the youthful aspirant for histrionic honors, induced him to accompany him to England, and try his fortunes in another hemisphere, where prejudice against color would be no barrier for his advancement.”[4] Although Aldridge achieved relatively swift recognition in London when he, at age 18, landed his first high-profile role as Oroonoko in The Revolt of Surinam; or, A Slave’s Revenge at the Royal Coburg Theatre in 1825, Wallack’s rose-colored vision of Aldridge’s reception across the Atlantic was almost immediately punctured. Numerous London critics penned harsh and unreservedly racist critiques of Aldridge’s performances, even though audiences were almost universally enraptured by his versatility as an actor, singer and dancer. Contrary to his generally hostile critical reception in London, however, Aldridge went on to achieve both critical and commercial success outside of the capital city. Bernth Lindfors, a preeminent scholar and biographer of Aldridge, offers the following synopsis:

“For the next twenty years Aldridge played almost exclusively in the provinces, building up a loyal following and a considerable fortune. He was on the road most of the year, performing in cities, towns, and villages throughout the British Isles. Restless for new challenges, he extended his Shakespearean repertoire, experimenting with white roles such as Shylock, Richard III, Hamlet, Macbeth, and Lear. In July 1852 he set out on his first major European tour and earned standing ovations wherever he went. After three years abroad, he returned to England laden with medals, decorations, and honors, but he still could not find regular engagements in London. He trouped through the provinces for a while, toured Europe again, then came back to England once more. By this time he was world-famous, but success on the London stage continued to elude him. He spent the last six years of his life performing principally in Russia and France, countries where he was acclaimed as one of the greatest tragedians of all time.”[5]

Throughout the course of his illustrious career, Aldridge was awarded many honors worldwide, including: in Haiti, Commission in the Army of Haiti; in Ireland, Brother Mason of the Grand Lodge and Brother of the Grand Royal Arch Chapter; in Austria, the Gold Medal of the First Class for Art and Science, the Medal of Ferdinand, and the Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold presented by the emperor himself; in Hungary, Honorary Member of the Hungarian Dramatic Conservatoire; in Switzerland, the White Cross; in Saxony, from the Royal Saxon House of Order, he became Chevalier Ira Aldridge, Knight of Saxony, a designation that was frequently advertised on theater posters starting in 1858; in Russia, Honorary Member of the Imperial Academy of Beaux Arts St. Petersburg, and the Imperial Jubilee de Tolstoy Medal; and finally, in England, British citizenship in 1863.[6]

One of Aldridge’s famed roles was that of Mungo in The Padlock, a farcical libretto composed and written by Charles Dibdin and Isaac Bickerstaff, respectively, and loosely modeled after the short story El celoso extremeño by Miguel de Cervantes. The two-act performance premiered in 1768 at London’s Drury Lane Theatre, where Dibdin himself, a white Englishman, performed the role of Mungo, a Black servant from the West Indies, in blackface. Dibdin’s rendition of Mungo was a racist caricature: a gullible, disloyal and drunken servant who was made to sing and dance on command.[7] Aldridge’s Mungo, however, was a more dignified portrayal, meant to convey the character’s humanity alongside the humor, and conversely, the inhumanity of his condition.[8] In his introduction to Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock’s biography of Aldridge, Ira Aldridge: The Negro Tragedian, playwright and theater historian Dr. Errol Hill notes that Aldridge transformed “the comic role of Mungo in The Padlock and turned it into both a lament and a rebellion against slavery.”[9] Aldridge was an outspoken abolitionist, and often capitalized on his figurative and literal platform to directly address his audience on the evils of slavery and other societal inequities.

The present lot depicts Aldridge as Mungo at the moment when El celoso extremeño (translated into English as “The Jealous Husband”) Don Diego returns home from a trip to find his servant Mungo imbibing in his cellar and elsewhere, Leonora—the young woman and object of his affection who he has confined in the care of his servants—in the arms of her lover Leander. Both Don Diego (upper-left) and Aldridge as Mungo appear in fine English dress, with plush scarlet upholstery and chartreuse drapery flanking the scene. A very similar painting to the present lot can be found in the Ira Aldridge Collection at Northwestern University’s Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections. That work is by an unknown artist, dated circa 1840 and originally from the collection of Professor Bernth Lindfors, Emeritus Professor of English and African Literature at the University of Texas, Austin and quoted herein.[10] While the artist and origin of the present lot are unknown, the original wood stretchers have been professionally tested and identified as a species from the White Pine Group, likely from the Pinus strobus species, which is native to the northeastern United States and Canada. While this fact alone does not confirm that the painting is American in origin, the work is nonetheless an important artifact in the history of American theater.

Regardless of the present lot’s unknown origins, its tacit portrayal of Aldridge as inhabiting dissonant realms—that of a stylish, respected and charismatic performer captive to the peering, curious but often critical gaze of his largely white European audiences—is perhaps unintentionally but presciently conveyed. Aldridge unexpectedly died a prolific and commercially successful actor while visiting Łódź, Poland in 1867. Aldridge was a legendary and inspirational figure within the African American community, so when news of his death reached the United States, several Black theater groups adopted his name for their companies in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and New Haven, among other cities.[11] Dr. Errol Hill recounts: “By the time of his death in 1867 he had performed over forty major roles on the legitimate stage, not only in Britain and Ireland but also in some thirty cities of Europe and Russia. During a career that spanned four decades, he gained several honors from heads of state for his convincingly realistic portrayals in comedy and tragedy, particularly in the great dramas of Shakespeare.”[12] Aldridge is increasingly recognized as a trailblazing luminary in the history of African American theater, and his enduring legacy as the first Black Shakespearean actor on the world stage has inspired generations of performers.

[1] Bernth Lindfors, Ira Aldridge: The Early Years, 1807-1833 (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2011), 4.

[2] James J. Napier, James C. Napier and Stanley B. Winters, ‘“African Trajedian’ in Golden Prague: (Some Unpublished Correspondence of Ira Aldridge),” Negro History Bulletin 32, no. 7 (1969): 23, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24767074.

[3] Alex Ross, “Othello’s Daughter: The Rich Legacy of Ira Aldridge, the Pioneering Black Shakespearean,” The New Yorker, July 22, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/29/othellos-daughter.

[4] Bernth Lindfors, Ira Aldridge: The Early Years, 1807-1833 (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2011), 34.

[5] Bernth Lindfors, ‘“Nothing Extenuate, Nor Set Down Aught in Malice’: New Biographical Information on Ira Aldridge,” African American Review 28, no. 3 (1994): 458, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3041981?origin=crossref&seq=1.

[6] Susan Russo, “An Extraordinary Early American in Europe,” Natural Selections, The Rockefeller University, July 7, 2014, https://selections.rockefeller.edu/an-extraordinary-early-american-in-europe/.

[7] J. R. Oldfield, “The ‘Ties of Soft Humanity’: Slavery and Race in British Drama, 1760-1800,” Huntington Library Quarterly 56, no. 1 (1993): 8-9, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3817716.

[8] Herbert Schendl, “Language Choice as a Dramatic Device in an Early Viennese Adaptation of Isaac Bickerstaff’s ‘The Padlock,’” Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 32, no. 1 (2007): 38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43025782.

[9] Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock, Ira Aldridge: The Negro Tragedian (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1993).

[10] Unknown artist, Portrait of Ira Aldridge as Mungo (The Padlock), circa 1840, oil on canvas, Ira Aldridge Collection, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ira_Aldridge#/media/File:Portrait_of_Ira_Aldridge_as_Mungo_by_an_unknown_artist,_undated.jpg;%20https://findingaids.library.northwestern.edu/repositories/7/archival_objects/527728.

[11] Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch, A History of African American Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 46.

[12] Errol G. Hill, “S. Morgan Smith: Successor to Ira Aldridge,” Black American Literature Forum 16, no. 4 (1982): 132, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2904219.

Condition Report

Frame: 30 1/4 x 26 inches.

In overall fine condition. Retaining a fairly even varnish throughout. Craquelure visible in areas throughout. The frame shows age, though it is likely replaced. Appears to retain the original stretchers and is on the original canvas, though at some point it was conserved, having the canvas removed and adding a 1" newer canvas to the edge so that it could be reattached to the stretchers. This was a necessary conservation as the work was likely deteriorating in corners and at the nail holes. Newer nails now hold the canvas to the stretchers. Examination under UV shows a few small areas of overpainting, but no evidence from the back of there having been any repaired tears or significant losses.

In overall fine condition. Retaining a fairly even varnish throughout. Craquelure visible in areas throughout. The frame shows age, though it is likely replaced. Appears to retain the original stretchers and is on the original canvas, though at some point it was conserved, having the canvas removed and adding a 1" newer canvas to the edge so that it could be reattached to the stretchers. This was a necessary conservation as the work was likely deteriorating in corners and at the nail holes. Newer nails now hold the canvas to the stretchers. Examination under UV shows a few small areas of overpainting, but no evidence from the back of there having been any repaired tears or significant losses.

The physical condition of lots in our auctions can vary due to

age, normal wear and tear, previous damage, and

restoration/repair. All lots are sold "AS IS," in the condition

they are in at the time of the auction, and we and the seller make

no representation or warranty and assume no liability of any kind

as to a lot's condition. Any reference to condition in a catalogue

description or a condition report shall not amount to a full

accounting of condition. Condition reports prepared by Hindman

staff are provided as a convenience and may be requested from the

Department prior to bidding.

The absence of a posted condition report on the Hindman website or

in our catalogues should not be interpreted as commentary on an

item's condition. Prospective buyers are responsible for

inspecting a lot or sending their agent or conservator to inspect

the lot on their behalf, and for ensuring that they have

requested, received and understood any condition report provided

by Hindman.

Please email katiebenedict@hindmanauctions.com for any additional information or questions you may have regarding this lot.