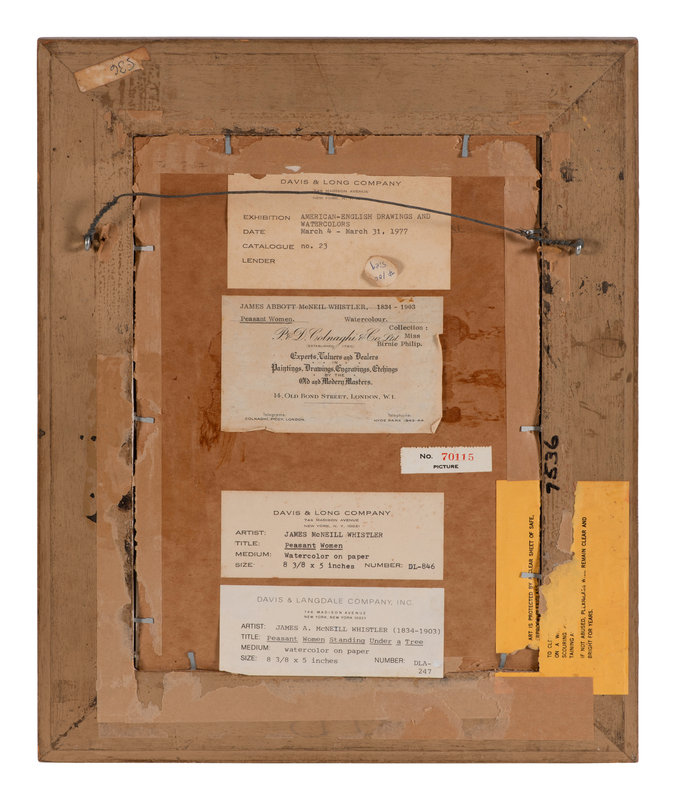

Provenance:

The Artist (in Whistler’s studio at 8 Fitzroy Street, London, on February 16, 1901)

bequeathed to Rosalind Birnie Philip, the Artists' sister-in-law, 1903 (still in studio)

(possibly) P. & D. Colnaghi, London, 1943 (as Breton Fisherwomen)

Private Collection, London, purchased from the above, 1943

Private Collection

P. & D. Colnaghi, London

Davis & Long, New York

Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Spencer, New York, purchased from the above, 1971

Davis & Long, New York

Private Collection, purchased from the above, 1977

Davis & Long, New York, 1981

Acquired from the above by the present owners, 1982

Exhibited:

London, P. & D. Colnaghi, Exhibition of English Paintings, Drawings, and Prints, February 23 - March 19, 1971, no. 107, pl. XXIX, illus. (as Peasant Women)

New York, Davis & Long, American-English Drawings and Watercolors, March 4 - 31, 1977, no. 23, illus. (as Peasant Women)

Loaned to Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, 1984

New York, M. Knoedler & Co., Notes, Harmonies and Nocturnes, November 30 - December 27, 1984, no. 126, p. 87, illus. (dated to c. 1890)

Literature:

Margaret F. MacDonald, James McNeill Whistler Drawings, Pastels and Watercolors: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London, 1995, cat. no. 1366, p. 481, illus.

Lot note:

James McNeill Whistler created watercolors throughout his life, beginning with a sketchbook he kept in his youth in St. Petersburg, Russia. However, he did not explore the medium in earnest—in salable works—until the 1880s. At the time, ceasing large-scale urban river views and ambitious studio pictures, he turned to watercolor to assert his originality, expand his market, and establish his place in the history of art, by challenging his predecessors in the venerable British watercolor tradition. He also took great pleasure in the medium, describing his watercolors in his writings as “delightful little things” and “amazing beauties.” Free of social commentary, and executed with fluidity, delicacy, subtlety, and vivacity, these works led critics to reconsider the accusations of slapdash carelessness that had led to his libel suit against John Ruskin in 1877 (which had forced him to declare bankruptcy). Whistler used watercolor in London (for figural images and Chelsea street scenes) and on travels to the English coast as well as across the Channel to Dordrecht, Brussels, Amsterdam, Dieppe, Calais, and Brittany. Peasant Women Standing under a Tree is among a group of works Whistler rendered in Brittany during a two-month summer trip in 1893. The trip—his third and last to Brittany—occurred during a period when he and his wife Beatrice were living in Paris. They sojourned in the Côtes-du-Nord region (now Côtes d’Armor), along Brittany’s northern coast, where they visited Vitré, Lannion, and Paimpol in July and Perros-Guirec in August. At one point they traveled to Isle de Bréhat, a mile off the north coast of Brittany, where Whistler kept a sketchbook featuring two drawings of peasant girls, perhaps related to this watercolor.

This watercolor is among only a few instances in which Whistler addressed the popular subject of French peasant life. However, he avoided the romantic sentimentality captured in such works by other artists, focusing on the intriguing aesthetic opportunities before him, which he cleverly united in a deceptively simple arrangement. Drawing the viewer’s eye upward from his low vantage point, Whistler divided the vertical arrangement at the center, between earth and sky. The influence of Japanese prints is apparent in the juxtaposition of the twisting line of a bare tree intersecting the work’s horizontal axis, where figures of peasant women along a receding wall converse, perhaps while drawing water from a well. There is an intriguing connection between this image and one by Camille Corot, Wall, Côtes-du-Nord, Brittany, c. 1855 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), depicting a similar undulating barren plateau where peasant women gather at a wall. Whistler’s close observation of light effects verifies his plein-air method. He applied translucent washes throughout to convey the dappled effects of the broken, scudding clouds, while recording the somber browns and grays of the women’s clothing, which suggest their integral place within the similarly toned terrain. The brownish-gray shadows in which the women stand imply, tantalizingly, that the tree actually had a high canopy of leaves, omitted by Whistler due to his perspective. A darkening patch in the sky suggests that a storm is brewing but the liquid blues (probably created with the Antwerp blue in Whistler’s watercolor palette) gives the work a glowing warmth. Paralleling the lone tree is a flagpole, perhaps rising from a distant fort. From it, a flag, rendered in saturated cobalt, seems to hover over the figure at the center of the composition, her red-toned face marking the work’s vanishing point and engaging the viewer, whom she faces. In conversation with her is a woman with her back to the viewer. Whistler silhouetted the triangle of her coif—the white head covering typically worn by French peasant women—against an area of vaporous turquoise sky. He made use of the exposed paper for the flaps and cones of the coifs of the other women in the scene as well as in spots, such as along the horizon, adding to the work’s luminosity.

In Whistler’s studio in 1901, and still there at the time of his death on July 17, 1903, Peasant Women Standing under a Tree was inherited by Rosalind Birnie Philip (1873–1958), the younger sister of Whistler’s wife Beatrice (1857–1896). Twenty-two at the time of Beatrice’s death, Rosalind became Whistler’s ward and secretary, managing his household in Chelsea, and Whistler made her the sole beneficiary and the executor of his will. Her holdings of Whistler’s art and correspondence are the core of the Whistler collection, given by Rosalind to the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow. However, over the years Philip sold a number of Whistler’s works through Colnaghi, the London art gallery, established in 1760. This was probably the watercolor purchased from Philip by Colnaghi on June 28, 1943, and sold that day to a private collector, who sold it to another private collector shortly thereafter. It was back at Colnaghi in 1971 and included in an exhibition February–March of that year, with its former collection listed in the catalogue as “Miss Birnie Philip.” Most of Whistler’s extant post-1879 watercolors are in public collections (the largest groups of these works belong to the Freer Museum and the Hunterian); Peasant Women Standing under a Tree is among a small number of Whistler’s post-1879 watercolors still in private hands.

Lisa N. Peters, PhD