Ed Paschke

Ed Paschke (1939-2004) was the quintessential Chicago-based artist of the Imagist generation which emerged in the disruptive period of the late 1960s. His work centered on what critic James Yood called “The human figure under duress” as he described the salient theme of Imagist art. Other prominent Imagists mined the psychological surrealism of lowbrow popular culture. Ed Paschke relied on photo imagery drawn directly from mass media.

He was interested in the adversarial relationship between individual identity and culture (which he defined as “symbols, metaphors, icons…and their baggage of referentiality”). He did not have a program, he was too inventive, the master Rule Breaker. In retrospect we see that he was working the grand theme of our age: The loss of self and hopeful redemption.

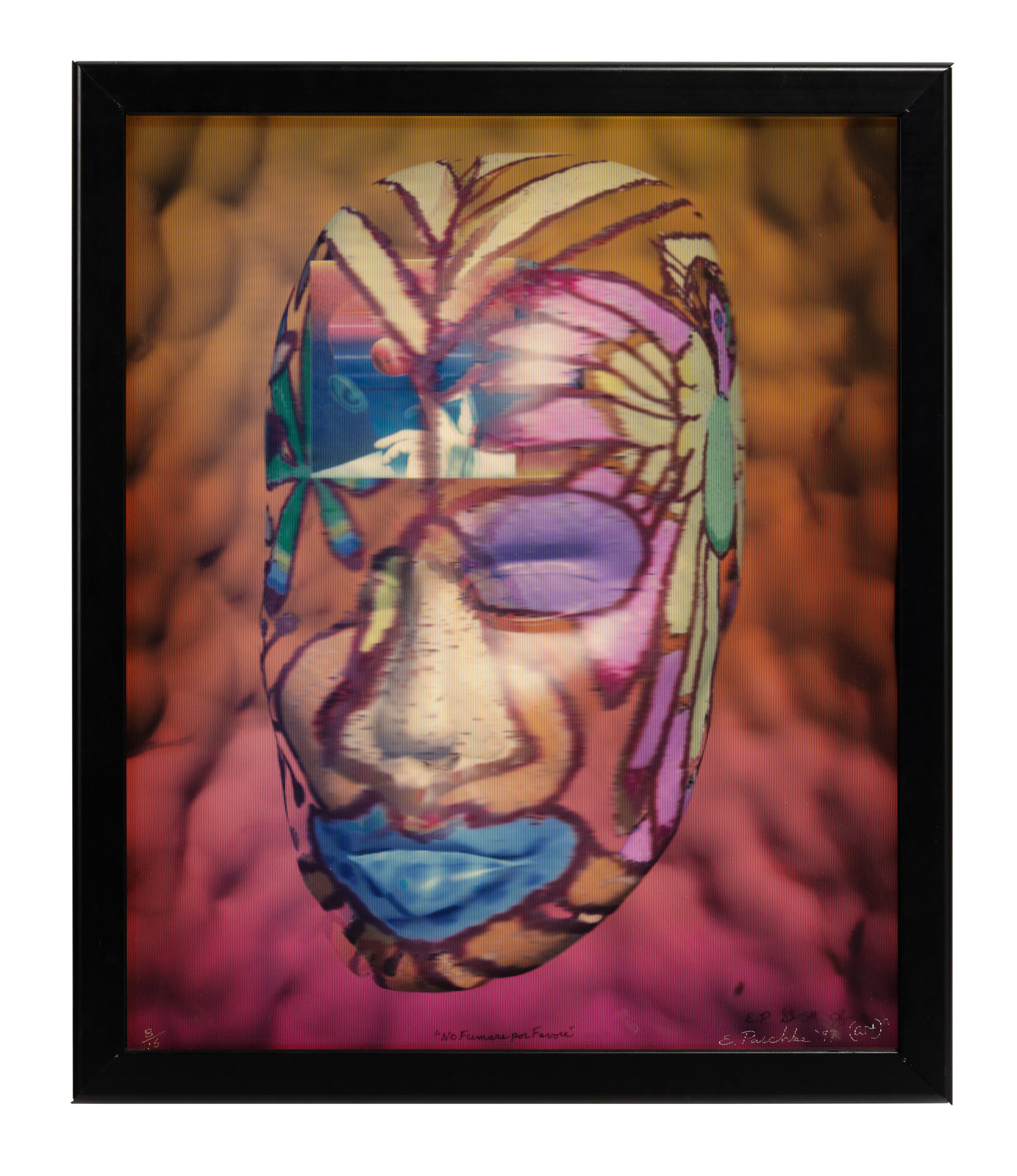

His early work centers on outsider identity, using ironic, comic exaggeration of figures and their costumes (wearable defenses), freaks and their anatomical damages. These characters were the excluded ones, while the viewer is the eager insider observer: a little smug, a little horrified, a little amused, a little sympathetic, like a visitor at a zoo or an extreme entertainment event. As Paschke’s work develops, the viewer is gradually absorbed by the surrounding, immersive, fractured context, like electric flashes, in an abusive culture. In his late work, the individual is replaced by mythic icons of public power, layered with color shards, as if torn from signs. Outsider and insider are then mingled and subsumed. The individual, the autobiographical, the essence of human identity, vanishes. Or it may seem, but Paschke was not a nihilist. He chose ambiguity, contradiction and paradox over finality.

Paschke held to a Law of Opposites, embracing the contradiction of one thing evoking its opposite alerting us to the “baggage” of ambiguous referentiality. That holds our attention and draws us close. We want to see Paschke’s art not only from the usual distance but also up close. We need to savor its surfaces and the paradox of image portraying the loss of self, and method asserting the redemption of self.

Ed Paschke was a superb craftsman. His technical mastery of drawing and painting is evident on every inch of surface. His confident touch, the featherweight delicacy of his method and the gentle assurance of his marks reveal his skill and his patient, generous, temperament. It is as though he was in private conversation with his art and its characters. He used sponges to apply and rub paint, tiny pointed brushes, pure pigments straight from the tubes and ink, crayon, and pencil that scarcely touched the surface. The canvas -and its helpless inhabitants- never felt his hand, or if they did, it was a caress, a kiss, a protective palm, a slight tap. The surface reveals Ed’s truth. There is his love and empathy, to protect and rescue each of them and each of us.

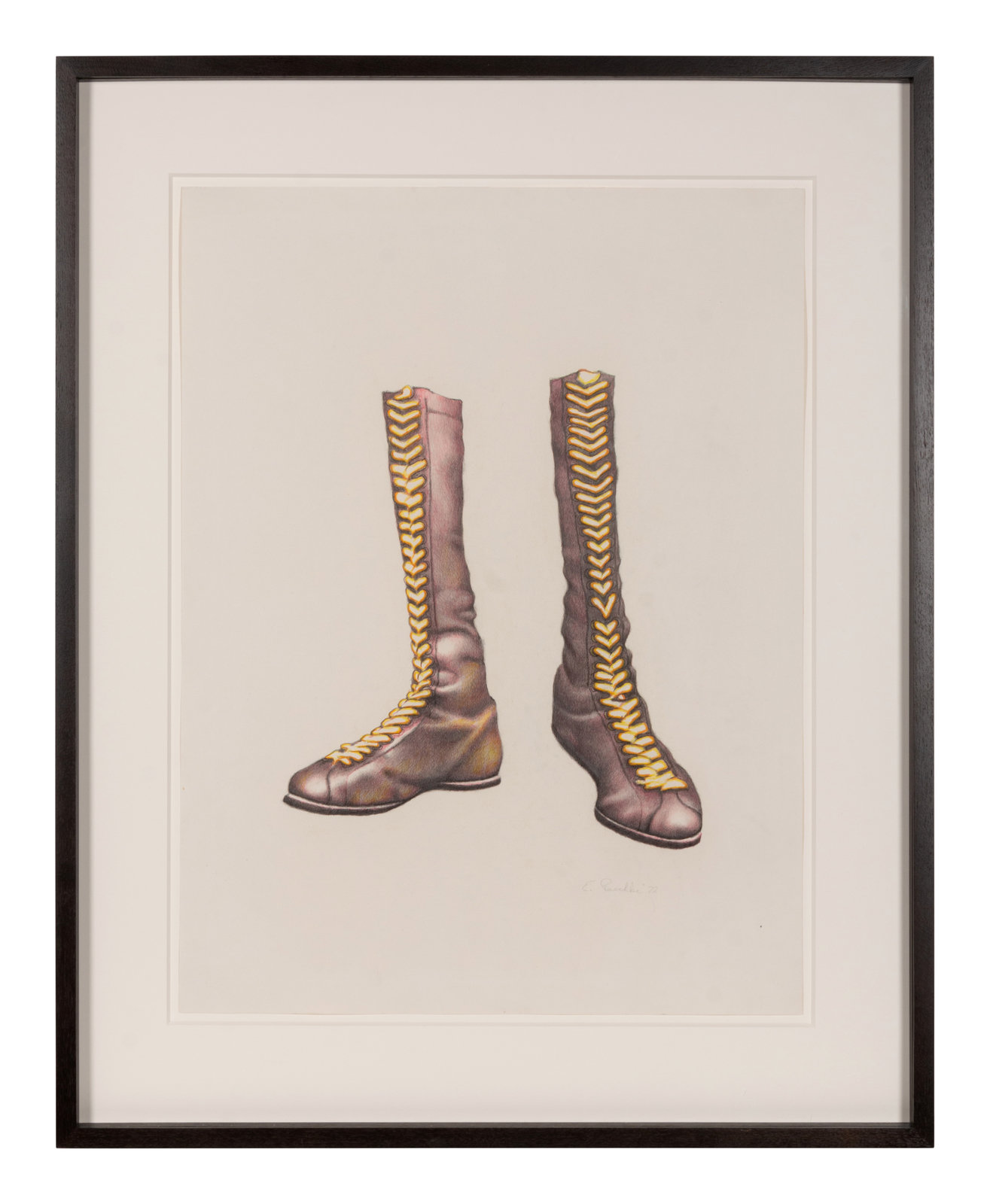

Boots, 1972, shows how visual concentration guided his pencil and crayons to an exacting, sculptural rendering that nevertheless retains a loose, almost casual, fading of edges. Thousands of bundled lines overlap, encircle and weave. They accumulate without effort. The boots are shown as in-use by an invisible wearer. Who? One thinks of bizarre militarism, maybe a crazed officer or costumed prankster. Elongated, too narrow, the boots convey oddness and tight discomfort. They are restrictive physical and psychological prosthetics. But the laces don’t bind. Instead they seem fluffy, almost like luminous chrysalises about to burst into butterflies — and freedom.

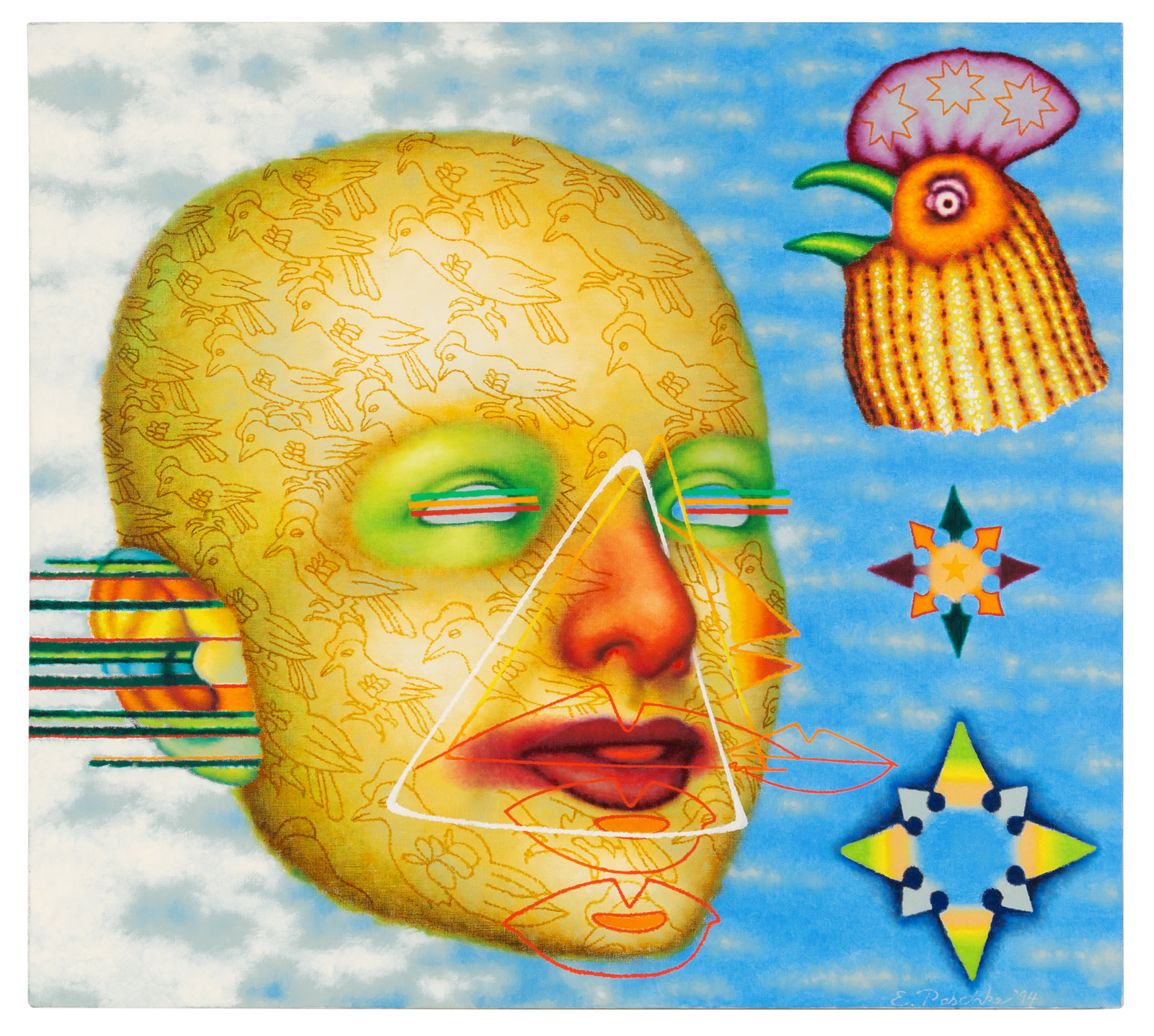

Sky Blue, 1994, represents Paschke’s moving on from the large celebrity or historical icon portraits of a few years earlier (such as his Elvis and Lincoln). Here Paschke reinvents a human scale generalized androgynous face overlaid with tattoo-like symbols of little chicks. They may be either dreaded or soothing chicks but they fill the head. (they may refer to his father’s inspiring carvings of birds). On the upper right a larger chicken without a wattle is neither fully hen nor rooster. This ambiguity leads us again to Paschke’s paradoxical law of opposites that resist efforts to explain his imagery as a simple narrative. Paschke employs wide ovals and lines to merge with the painted head. Together they suggest the five senses. Other symbols float nearby. It’s an uncertain private dialogue about personal identity happening in broad daylight. The paint application is more varied in this work, sometimes thick, vigorous; sometimes water thin and dotted, evoking the presence of studio hands-on working and experiment. Sky Blue shows how Paschke’s commitment to inventive at-the-moment problem solving was guided by his career-long maxim: “Show life in the picture plane.

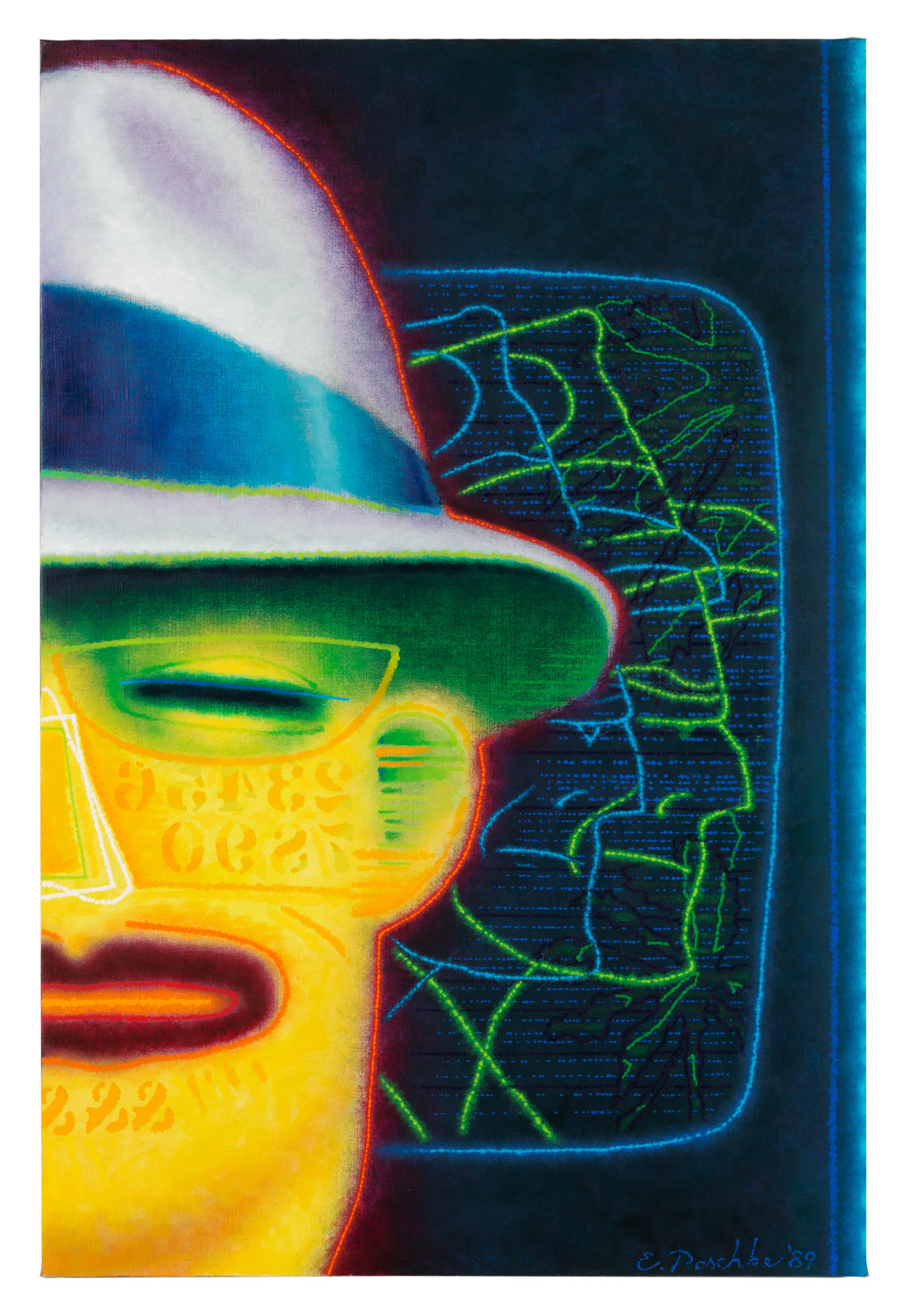

Tracer, 1989: The jittery, glowing face of the iconic comic strip Dick Tracy is surrounded by a TV screen and to its left a full color mirror image (also indicated by reverse numbers on the frontal face) of a wannabe Dick Tracy, a Tracer. The duo reflects the essential oneness of the two faces. The merging of icon with “the common man “ suggests the projection of self into cultural identity or the absorption of self by a fictional, flickering icon. The delicately painted surface is a clue to Paschke’s encouraging empathy for a Tracer, the character under a big 1940s gangland Fedora.

Spirit of Power, 1989, is a spectral image of a gun, one of many that Paschke made at this time. It’s an icon of gang violence and societal authority and defense, complicated further by the religious allusion of the INRI inscription and a cross. Meticulous rendering in several media, applied in succession, invite a visual delayering, as if peeling away the marks will reveal meaning. At this time Paschke was drawing over washes with ink dots that mimic his method of painting with the tips of small brushes, accumulating tone and illusion without obscuring the illumination from under-layers. There is a ritualist’s fondness for repetition in his method. It asks the viewer to participate in drawing and to contemplate the deceptive aura of an icon of sudden and terrible violence.

-William Conger, Artist; Professor Emeritus, Art Theory and Practice, Northwestern University