Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

Lot 65

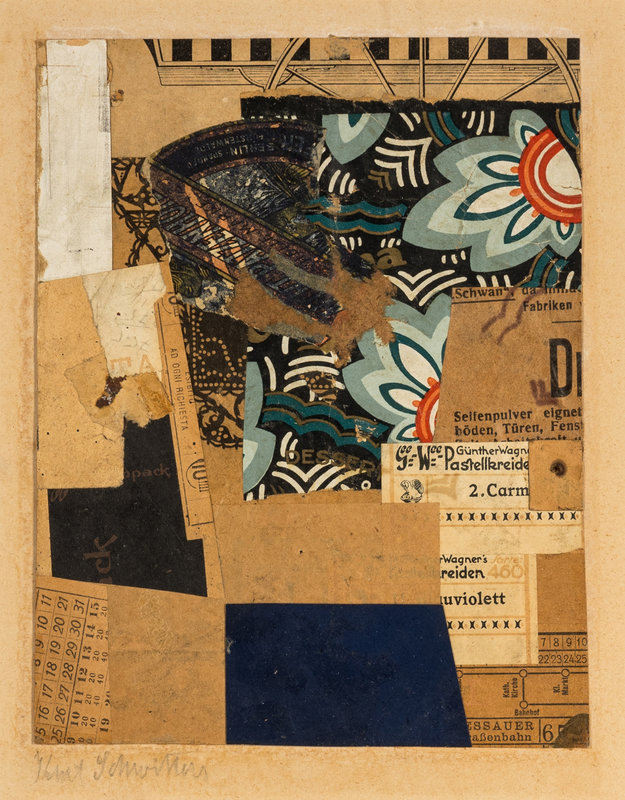

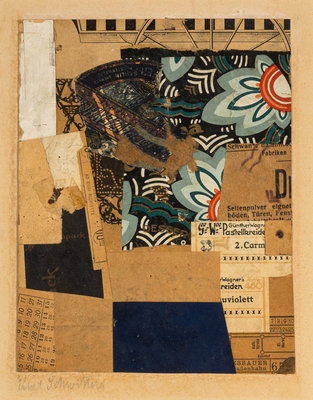

Kurt Schwitters

(German, 1884-1948)

Untitled (uviolett), c. 1926-28

Sale 1175 - European Art

May 18, 2023

10:00AM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$40,000 -

60,000

Price Realized

$25,200

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Kurt Schwitters

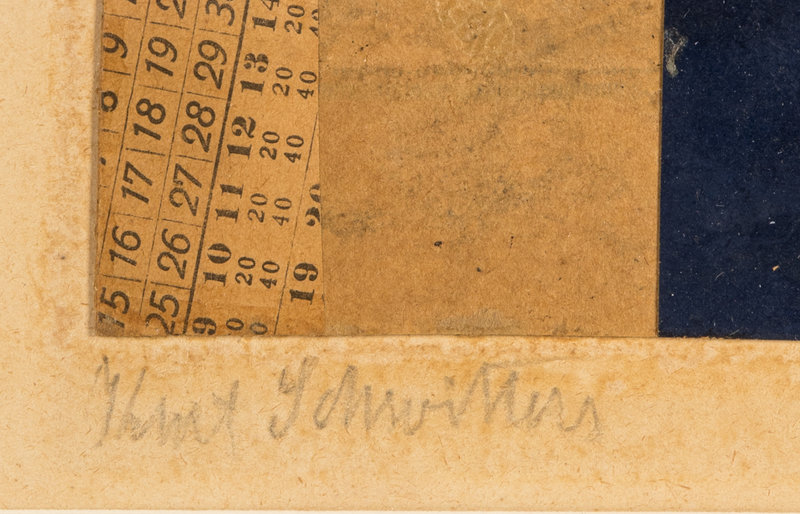

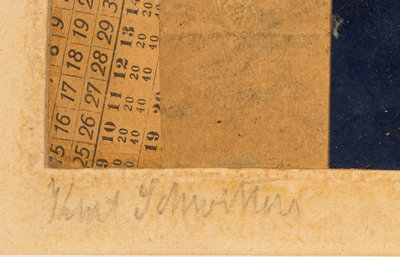

signed Kurt Schwitters (lower right)

7 1/4 x 5 1/2 inches.

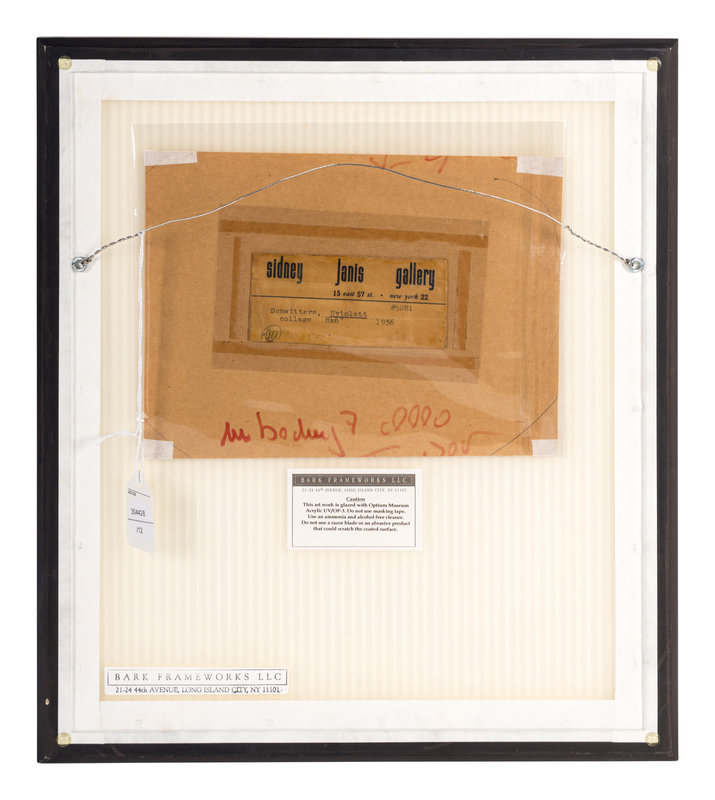

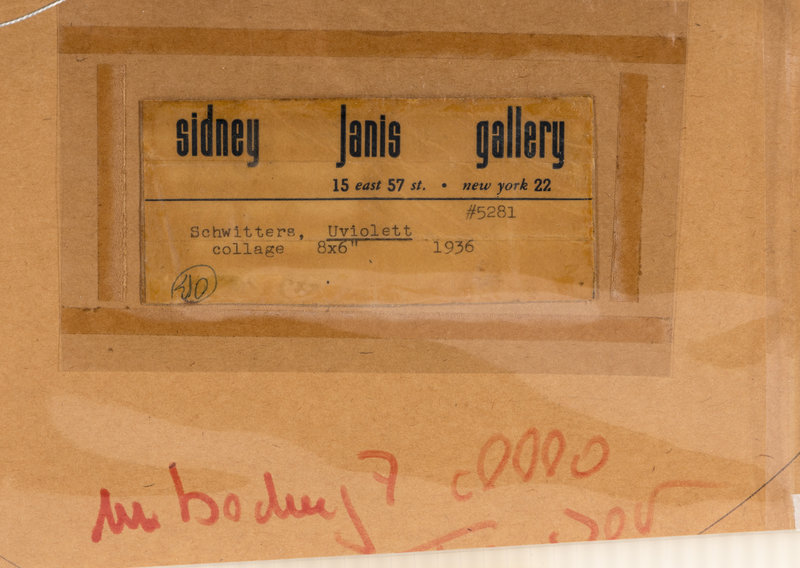

Property From the Estate of Lucia Woods Lindley

(German, 1884-1948)

Untitled (uviolett), c. 1926-28

paper collage on card mounted on paper

signed Kurt Schwitters (lower right)

7 1/4 x 5 1/2 inches.

Property From the Estate of Lucia Woods Lindley