Condition Report

Contact Information

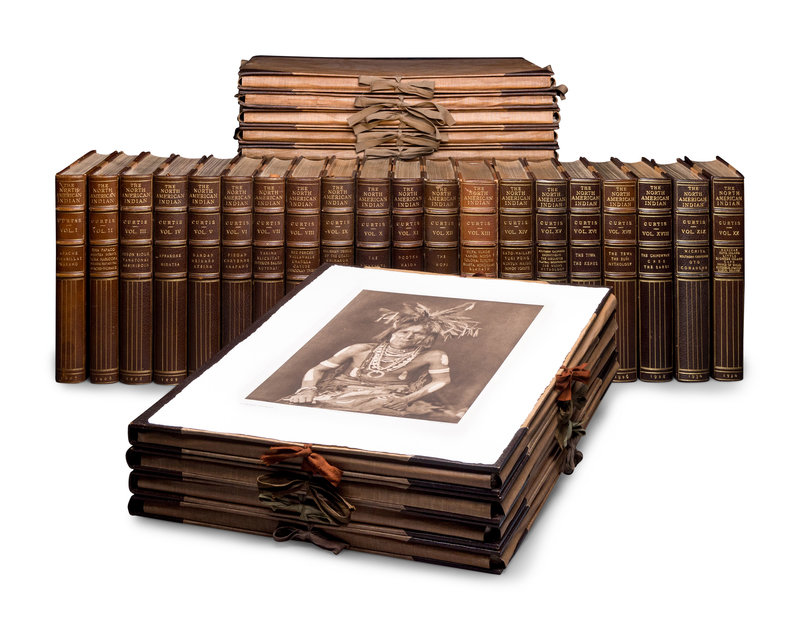

Lot 23

Lot Description

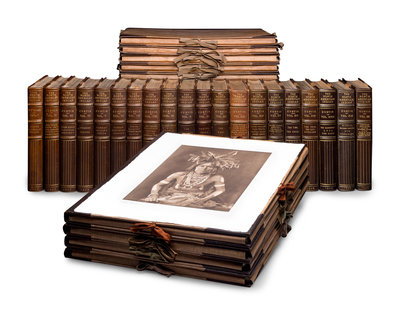

Together, 40 volumes, comprising:

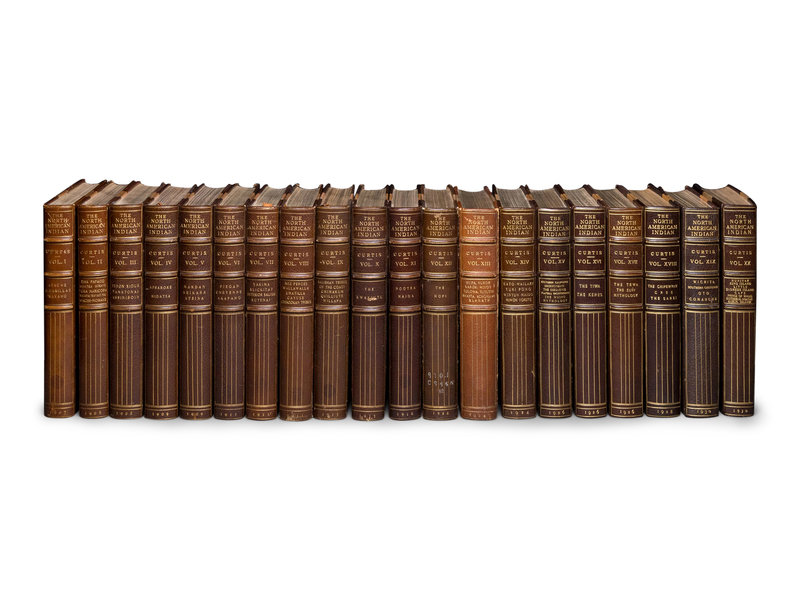

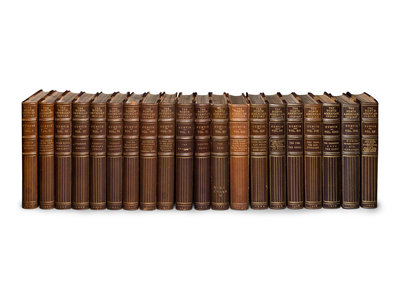

TEXT: 20 volumes, 4to (316 x 240 mm). 1,511 illustrations, comprising 1,505 photogravures, 4 maps and 2 diagrams. Original publisher's brown half morocco gilt, top edges gilt, others uncut, stamp-signed by H. Blackwell and Whitman Bennett.

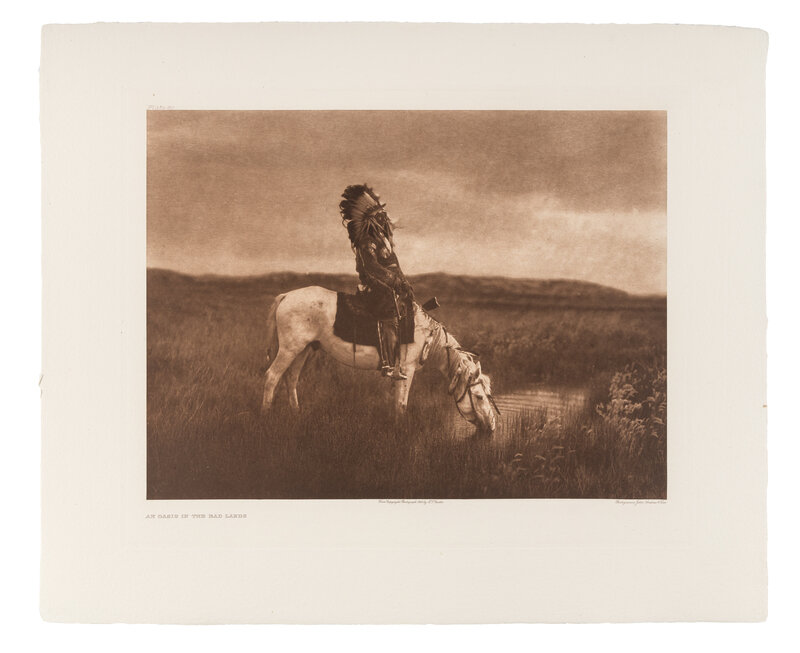

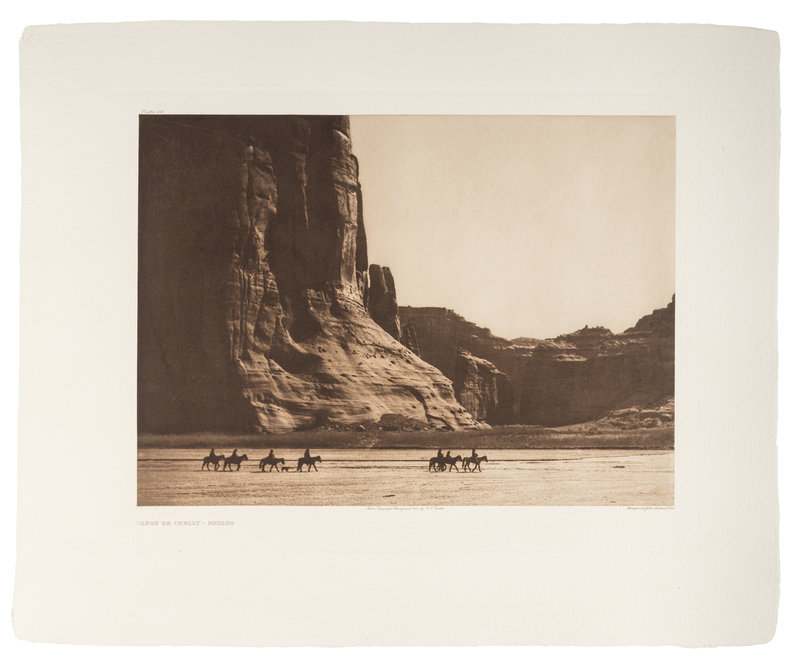

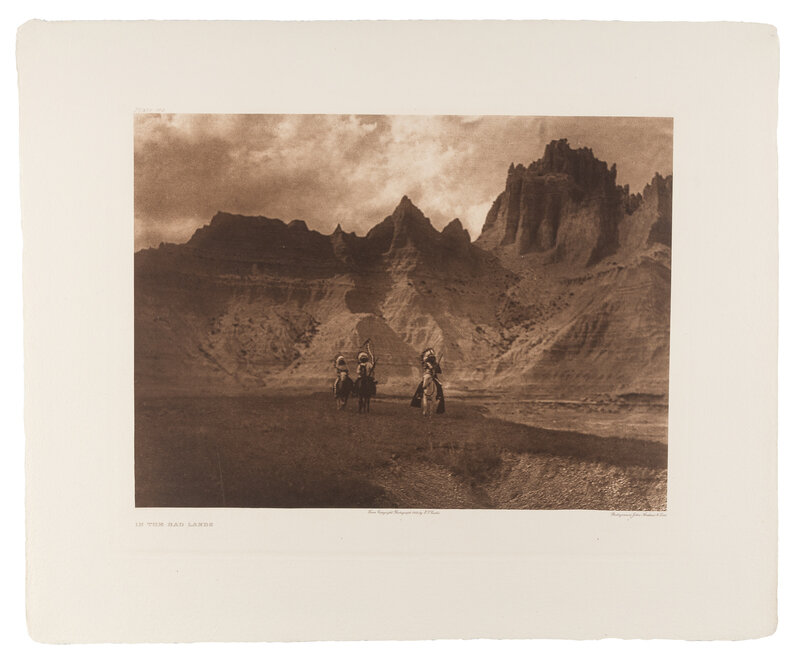

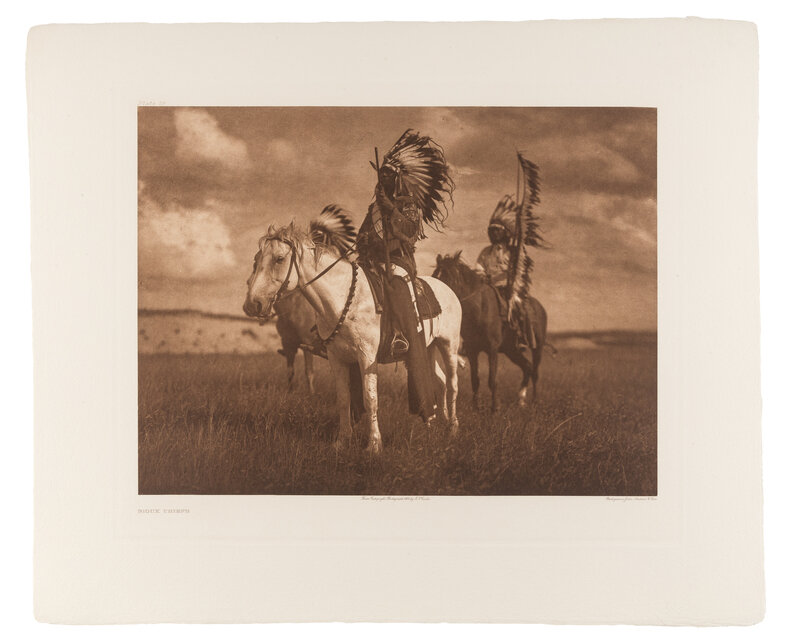

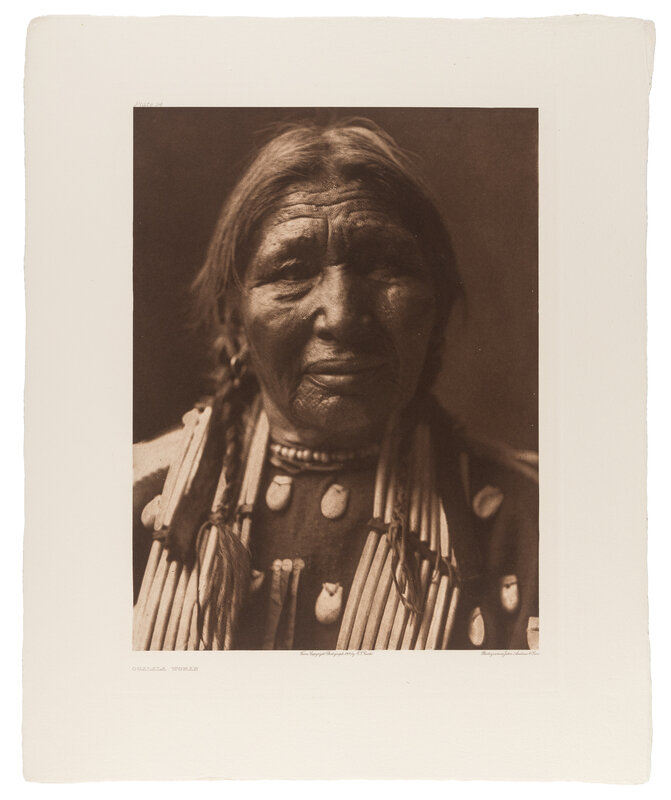

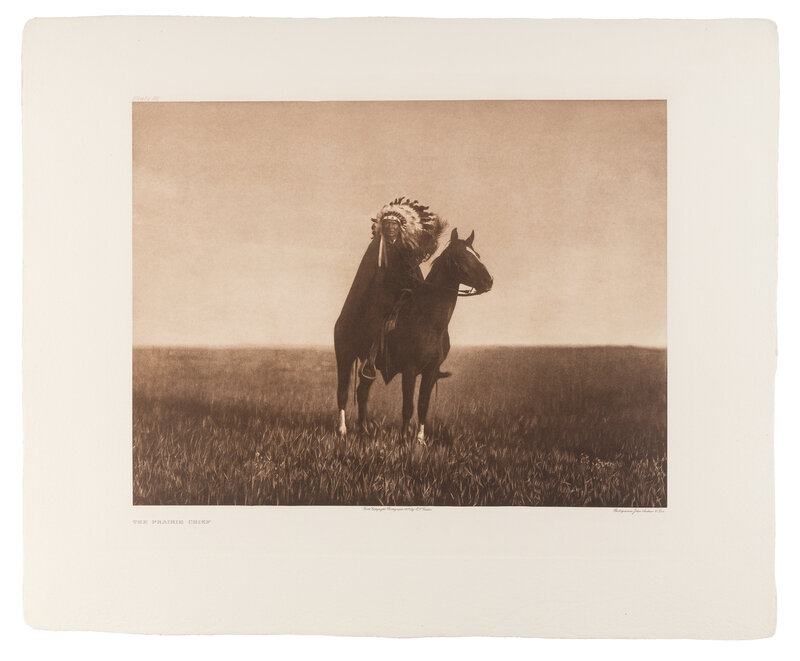

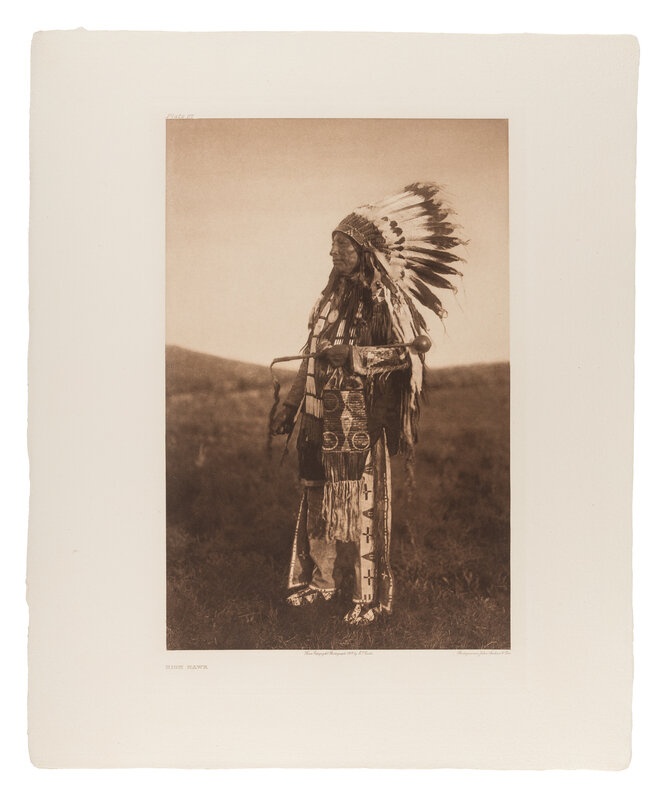

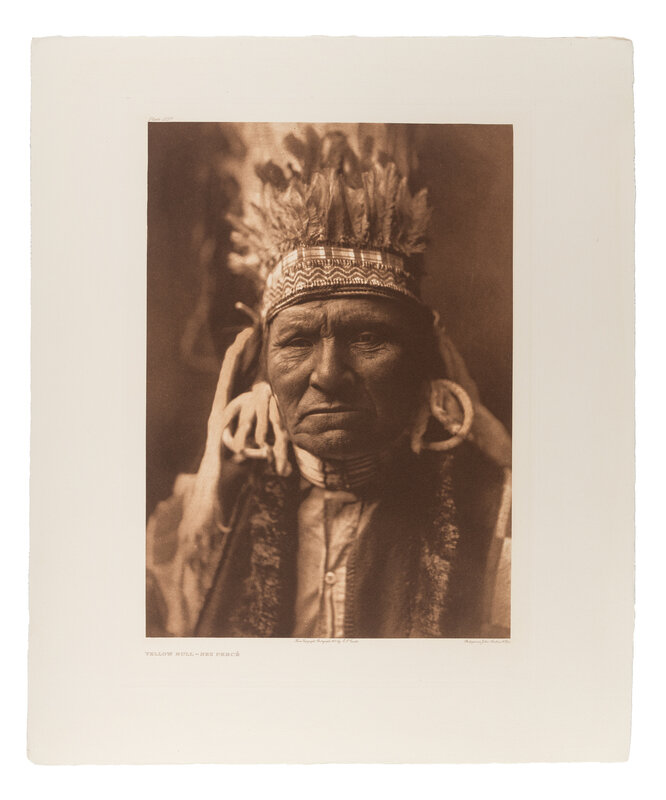

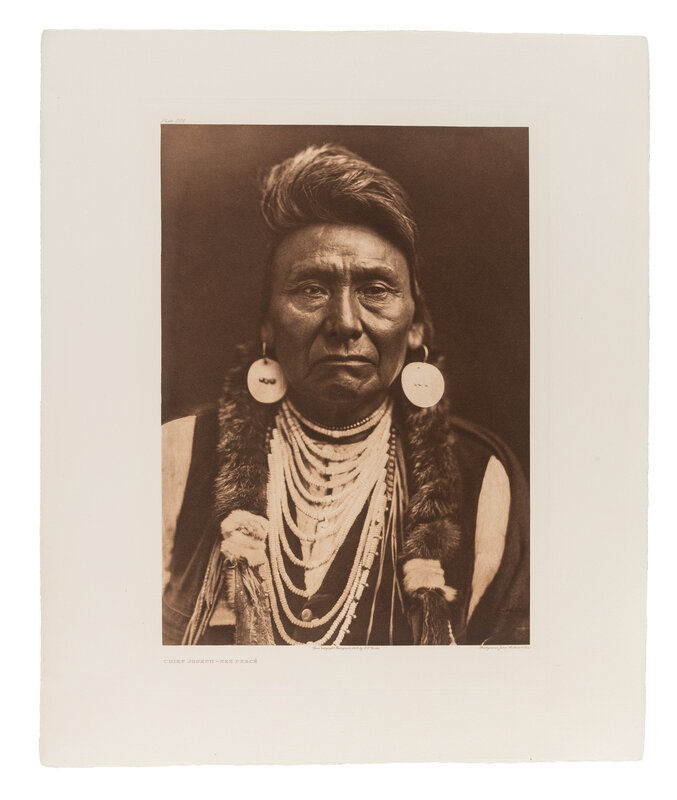

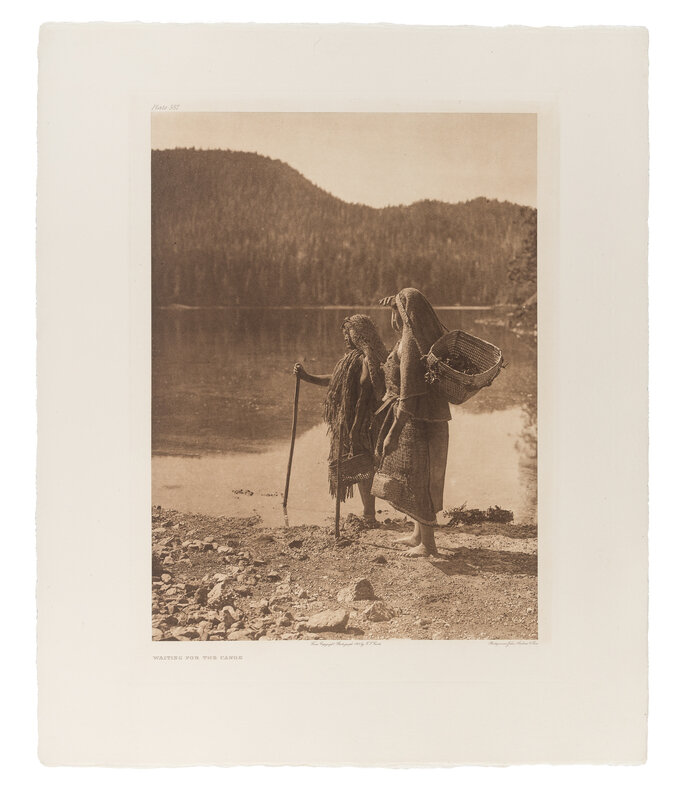

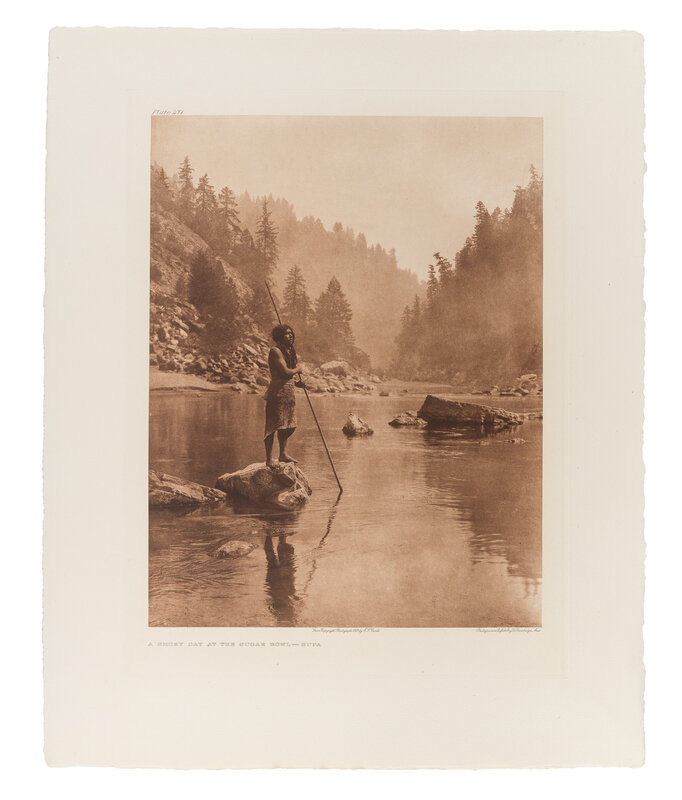

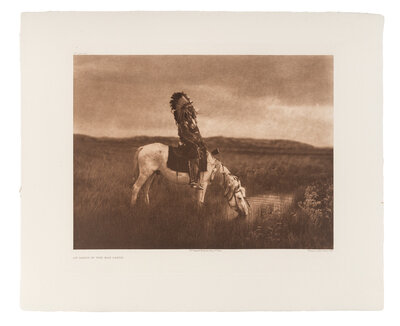

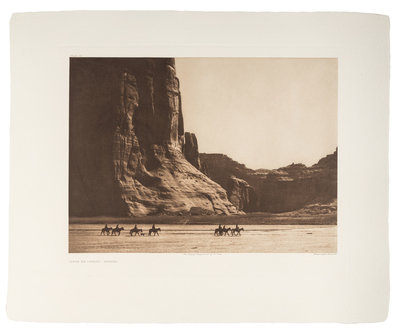

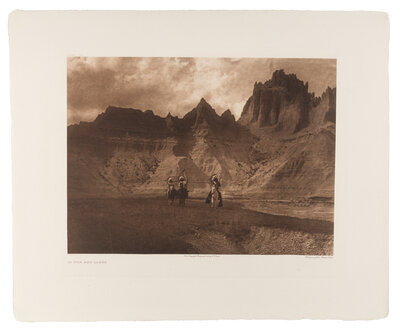

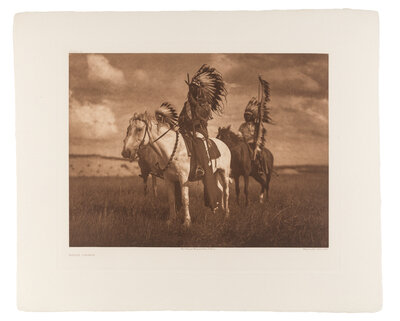

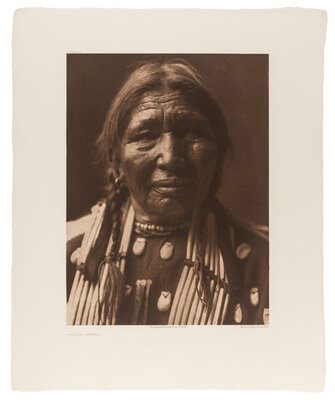

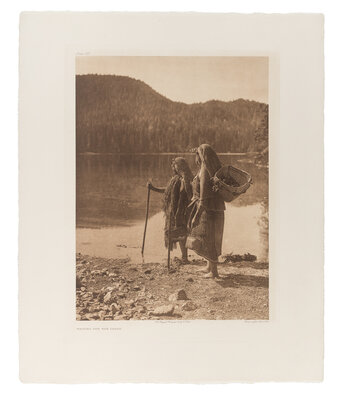

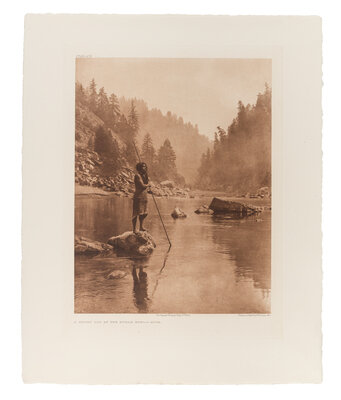

SUPPLEMENTARY LARGE PLATES: 20 volumes, large folio (570 x 450 mm). 723 photogravures in sepia on full sheets with deckle edges preserved (numbered 1-722, with two plates numbered 400); letterpress index leaves in each volume. Original publisher's half morocco, gilt-numbered in lower left corner of upper cover, original cloth ties.

LIMITED EDITION, number 88 of 500 proposed sets (but probably only 272 sets produced), the text on Japan vellum, the supplementary large plates on Van Gelder Holland, volume one signed by Edward S. Curtis and dated 1907.

PROVENANCE: The Free Public Library New Bedford, Massachusetts, original subscriber -- Sold to Louise G. Harper, later gifted to -- Reed College, Portland, Oregon -- Sold to a private individual -- Acquired by the present owner.

CONDITION:

Text volumes: Internally virtually free from characteristic offsetting and tissue burn. Small stamps or markings on title-pages and content leaves, and a few blank preliminary leaves and lists of plates; vol. XII with small stamps on versos of plates; a few hinges just starting. Bindings with light rubbing to corners and some joints; library markings to foot of one spine.

Plate portfolios: Internally very fresh; archival restoration to plates by Joel Oppenheimer Galleries, removing browning and offsetting from tissue guards and removing marginal collection stamps from the plates (conservation report available on request). Bindings with some light rubbing or wear to a few of the spines, a few volumes with tiny separations or slight cracking to spines, a few volumes with flap folds starting with occasional discreet repairs to small portions of hinges, cloth to flaps renewed in vol. XI; 4 portfolios with small library markings on upper covers; portfolio vol. XII lacking spine, one flap detached. Most volumes with small stamps, discreet manuscript annotations or bookplates on inner front covers. With extra portfolio volume for vol. VIII.

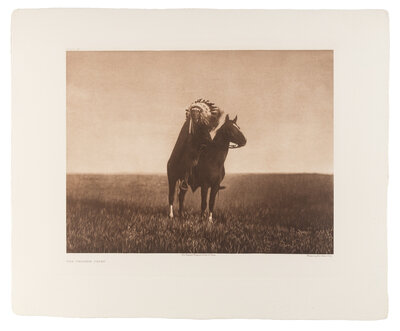

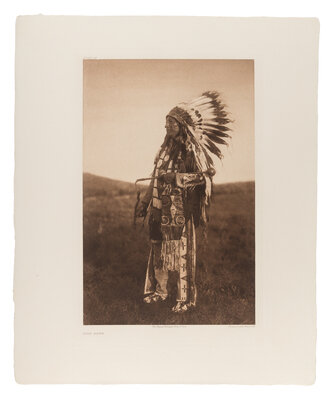

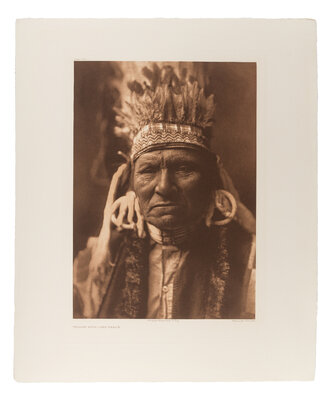

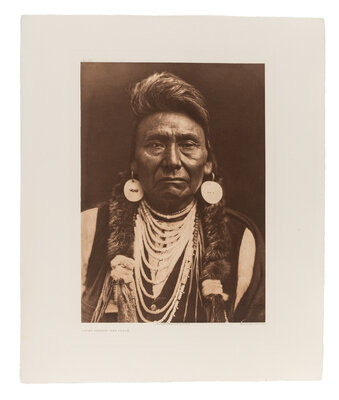

A COMPLETE SUBSCRIBER’S SET OF CURTIS’S MONUMENTAL WORK, one of the most compendious ethnographic records of native peoples in North America, and one of the most expensive undertakings in this history of book production. It stands as “AN ABSOLUTELY UNMATCHED MASTERPIECE OF VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY, AND ONE OF THE MOST THOROUGH, EXTENSIVE AND PROFOUND PHOTOGRAPH WORKS OF ALL TIME” (Cardozo, Sacred Legacy: Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian).

ORIGINS

Edward Sheriff Curtis was born on a farm near Whitewater Wisconsin in 1868, and moved with his family to Minnesota in 1874. His life there, living near the Chippewa, Menominee and Winnebago tribes, piqued his interest in American Indians. While in Minnesota, he also developed an interest in photography, and at the age of 12, he built a rudimentary camera consisting of two boxes, one inside the other, based on instructions he found in Wilson’s Photographics; he became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul at age 17. Curtis’s father’s ailing health prompted the family to move to Washington Territory in 1887. In Seattle, he partnered with Rasmus Rothi in a photographic studio, acquiring a 50% share for $150. Less than a year later, he partnered with Thomas Guptill to establish a new studio, Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers, on Second Avenue where he was known for producing the finest photographic work in the city.

While in the Pacific Northwest, Curtis became acquainted with the Native American tribes in the area. In particular, he learned about a Lushootseed woman, Kikisoblu, also known as Princess Angeline, who was the last living daughter of Chief Seattle. “When Curtis saw Angeline moving along the shore, the visible nearly dead…she looked at once like the perfect subject. There against the deep waters of Puget Sound, there with the snow-mantled Olympic Mountains framed behind her…with all of that, Curtis saw a moment from a time before any white man had looked upon these shores. He saw a person and nature, one and the same in his mind, as they belonged. A frozen image of a lost time: he must take that picture before she passed” (Timothy Egan, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, p.6).

While photographing Mount Rainier in 1895, Curtis had a chance encounter with a lost party and guided them to refuge at Camp Muir. The party included George Bird Grinnell, then the editor of Field & Stream and an acknowledged expert on the Plains Indians, C. Hart Merriam, Chief of the U. S. Division of Biological Survey. At Merriam’s suggestion in 1899, Curtis was appointed the official photographer of the Harriman Alaska Expedition, and the following year, he accompanied Grinnell to Montana to photograph the people of the Blackfeet and Piegan tribes. Near the end of that summer, Curtis told Grinnell that his mind was set that he would embark on a plan to photograph all intact Indian communities left in North America, to “capture the essence of their lives before that essence disappeared” (Egan p.50). Curtis believed that “the record, to be of value to future generations must be ethnologically accurate” (qtd. by Egan, p.50).

PUBLICATION AND SUPPORT: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN

One of the early supporters of Curtis’s work was President Theodore Roosevelt, who Curtis had met through a series of encounters in 1904. Curtis and Roosevelt bonded “over their mutual interests in the outdoors and the changing American West. The two also shared the then widely accepted but mistaken belief that the Indian Nations of the U. S. were a ‘vanishing race’” (Tim Greyhavens, “Duty Bound to Finish,” 2018, p.5). “The years 1904-05 were watershed times in the development of what would become Curtis’s life-long project” (Greyhavens, p.5). Curtis gained support for his work after mounting several successful exhibitions in Seattle and New York, and by the end of 1905, Roosevelt provided Curtis with a letter of introduction to help him find financial support for the project.

Curtis's introduction to J. P. Morgan, who would become the largest financial supporter of his work, came through Morgan’s daughter Louise Satterlee, who had seen his exhibition at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York in 1905. Curtis wrote a letter to J. P. Morgan outlining plan to “make a complete publication, showing picture and including text of every phase of Indian life of all tribes yet in a primitive condition, taking up the type, male and female, child and adult, their home structure, their environment, their handicraft, games, ceremonies, etc.; dividing the whole into twenty volumes containing fifteen hundred full page plates, the text to treat the subject much as the pictures do, going fully into their history, life and manners, ceremony, legends and mythology, treating it in rather a broad way so that it will be scientifically accurate, yet if possible, interesting reading” (qtd. in Greyhavens, p.9). Morgan offered $75,000 for a series on the North American Indian, to contain 1,500 photographs in 20 volumes, and in return, he was to receive 25 complete sets of the work and 300 original photographs.

The first two volumes appeared in 1907 and 1908, and immediately “the acclaim was seismic. In appearance and texture, the books were among the most luxurious ever printed” (Egan p.154). The images, printed in sepia tones from acid-etched copper plates produced by John Andrew & Son in Boston and printed by the Cambridge University Press, “were better than fine oil paintings” (Egan p.154). The New York Times acclaimed “nothing just like it has ever before been attempted for any people. He has made text and pictures interpret each other, and both together present a more vivid, faithful and comprehensive view of the North American Indian as he is to-day than has ever been made or can possibly made again…In artistic value the photogravures are worthy of very great praise. They are beautiful reproductions of photographs that in themselves are works of art” (qtd. in Egan, p.154).

In late 1909, noticing the financial deficits of Curtis’s project, Morgan directed that a new enterprise be formed. The newly-formed organization, North American Indian Company, would manage the finances and business side of Curtis’s work. After J. P. Morgan’s death in 1913, his son continued the family’s financial support of the project, ultimately providing at least half of the $1.5 million it took to complete the work. Though Curtis had received funding from other sources, the cost of the project, in part due to his failure to sell subscriptions, as well as debt from his divorce, crippled his business. By 1928, desperate for cash, Curtis sold the rights to his project to Morgan. In 1930, shortly following the publication of the final volume of The North American Indian, the North American Indian Company went bankrupt. In 1935, the Morgan family sold nearly everything related to The North American Indian to Charles Lauriat Books in Boston for $1,000 plus a percentage of future royalties.

LEGACY: “A BROAD AND LUMINOUS PICTURE”

Of the 500 planned sets, an estimated 272 were finished. “Only in recent years has the scope and depth of Curtis’s scholarship come to be appreciated. The North American Indian, the monumental work of a self-educated man, ‘almost certainly constitutes the largest anthropological enterprise ever undertaken’” according to Mick Gidley (Egan p.322). In all, Curtis took more than 40,000 photographs, recorded over 10,000 songs, wrote down vocabularies and pronunciation guides for 75 languages, and transcribed an untold number of myths, rituals, and religious stories from oral histories. Edward Curtis never profited from the production of his expansive and comprehensive publication, and lost his friends and marriage to his obsession, but “he always believed his words and pictures would come to life long after he’d passed – the artist’s lasting reward of immortality. A young man with an unlived-in face found his calling in the faces of a continent’s forgotten people, and in so doing, he not only saw history, but made it” (Egan p.325).

"Many Native Americans Curtis photographed called him Shadow Catcher. But the images he captured were far more powerful than mere shadows. The men, women, and children in The North American Indian seem as alive to us today as they did when Curtis took their pictures in the early part of the twentieth century. Curtis respected the Native Americans he encountered and was willing to learn about their culture, religion and way of life. In return the Native Americans respected and trusted him. When judged by the standards of his time, Curtis was far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance, and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking" (Laurie Lawlor, Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, p.6). His life-work, The Native American Indian, stands as a monument of American photography and illustrated-book production.

References: Howes C-965; Truthful Lens 40. See Timothy Egan, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, 2012. See Tim Greyhavens, “Duty-Bound to Finish: Edward S. Curtis and His Quest for Money to Complete The North American Indian,” December 2019. See Laurie Lawlor, Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, 2005

Property from the Dorros Family Collection