Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialists

Lot 50

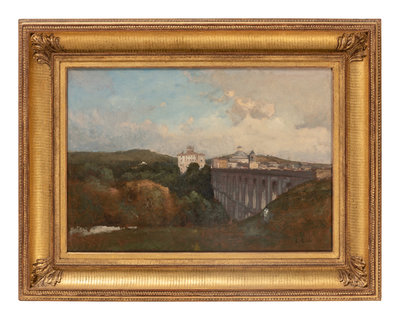

George Inness

(American, 1825-1894)

Viaduct at Laricha, Italy, c. 1872-74

Sale 1283 - Canvas & Clay: The Collection of Judith and Philip Sieg, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania

Oct 26, 2023

10:00AM ET

Live / New York

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$50,000 -

70,000

Lot Description

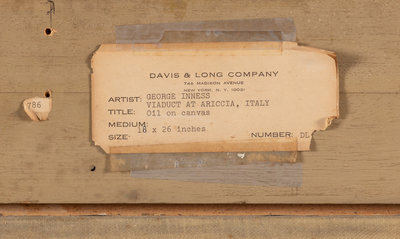

George Inness

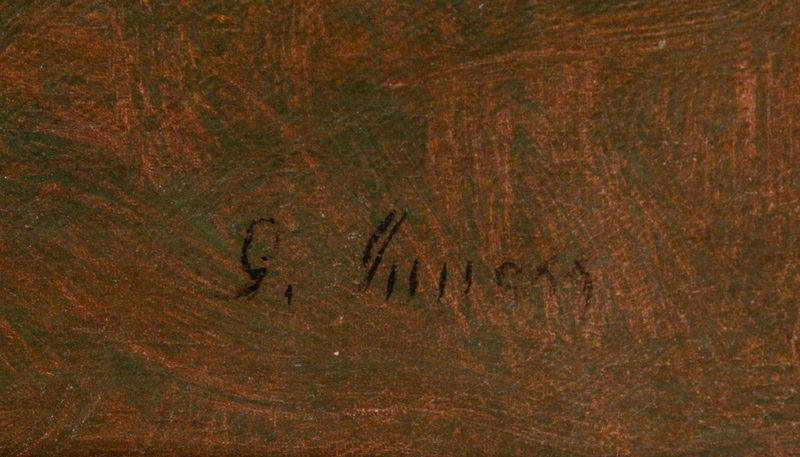

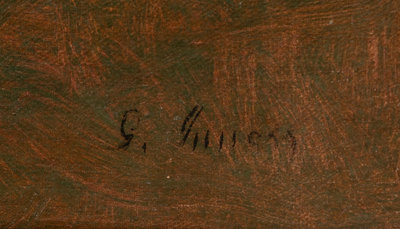

signed G. Inness (lower right)

18 x 26 inches.

The Collection of Philip and Judith Sieg, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania

(American, 1825-1894)

Viaduct at Laricha, Italy, c. 1872-74

oil on canvas

signed G. Inness (lower right)

18 x 26 inches.

The Collection of Philip and Judith Sieg, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania