Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialists

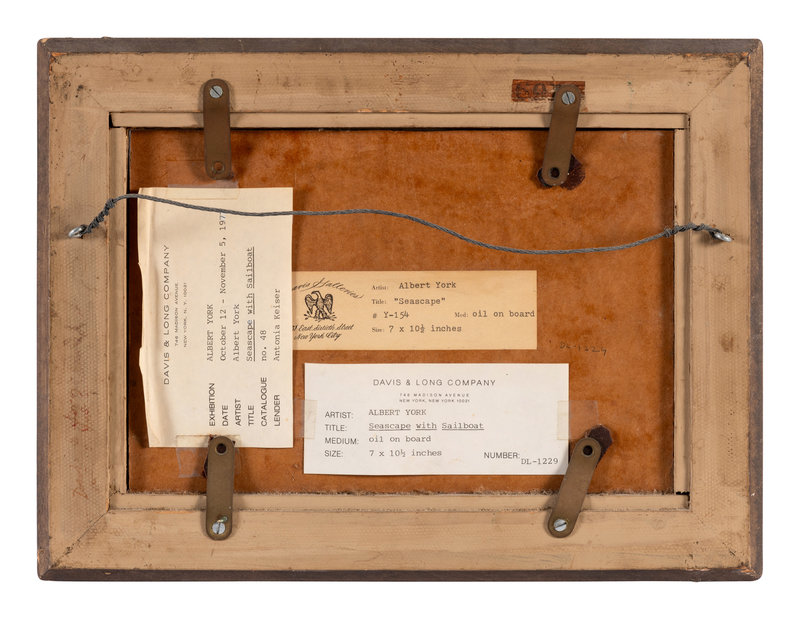

Lot 67

Albert York

(American, 1928-2009)

Seascape with Sailboat, c. 1970

Sale 1283 - Canvas & Clay: The Collection of Judith and Philip Sieg, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania

Oct 26, 2023

10:00AM ET

Live / New York

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$60,000 -

80,000

Price Realized

$50,400

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Albert York

7 x 10 1/4 inches.

The Collection of Philip and Judith Sieg, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania

(American, 1928-2009)

Seascape with Sailboat, c. 1970

oil on board

7 x 10 1/4 inches.

The Collection of Philip and Judith Sieg, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania