Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialists

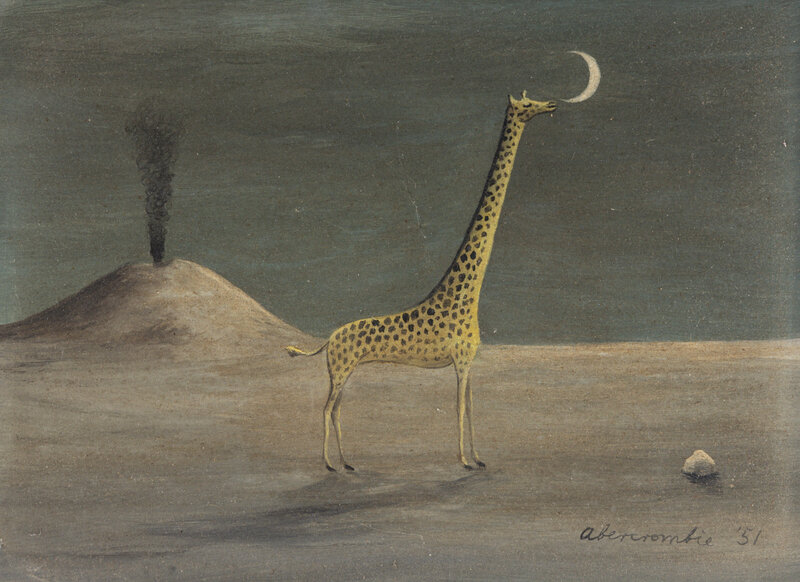

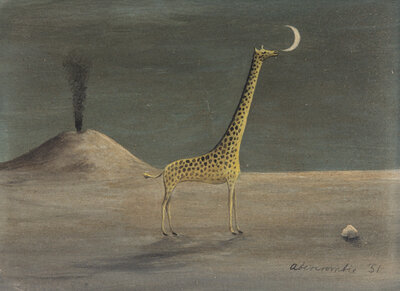

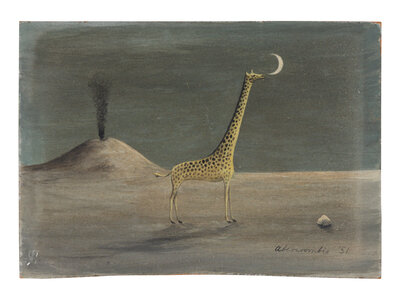

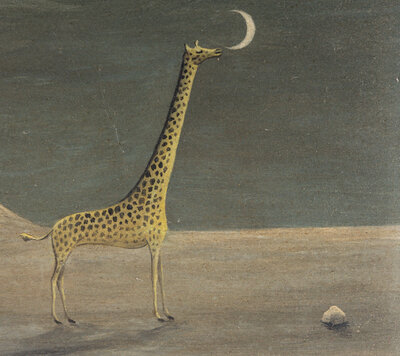

Lot 43

Gertrude Abercrombie

(American, 1909-1977)

Giraffe and Moon with Volcano (Giraffe and Volcano #2), 1951

Sale 1327 - Post War and Contemporary Art

Apr 24, 2024

10:00AM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$50,000 -

70,000

Price Realized

$266,700

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

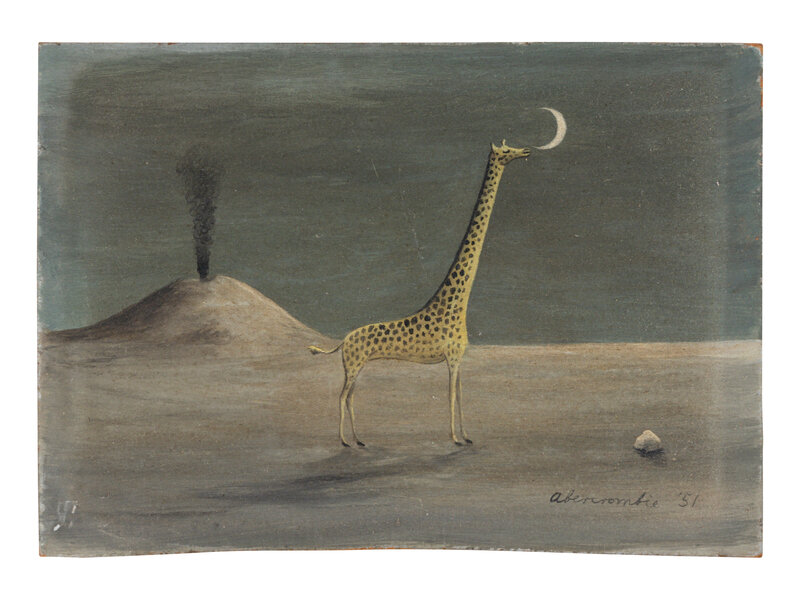

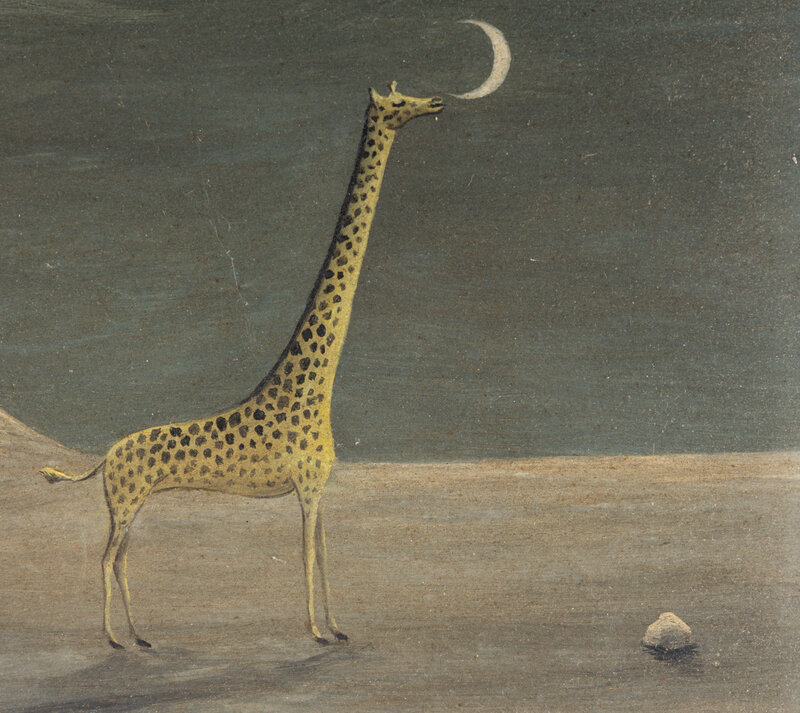

Gertrude Abercrombie

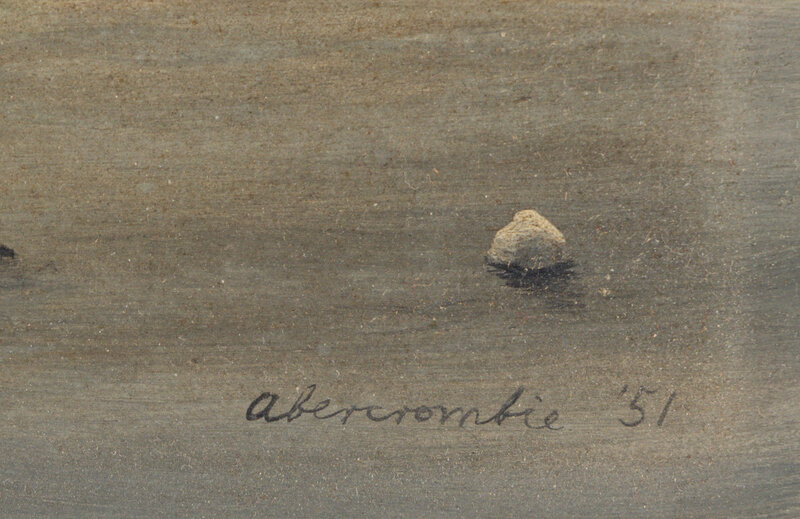

signed Abercrombie and dated (lower right)

5 x 7 inches.

(American, 1909-1977)

Giraffe and Moon with Volcano (Giraffe and Volcano #2), 1951

oil on masonite

signed Abercrombie and dated (lower right)

5 x 7 inches.