Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

Lot 428

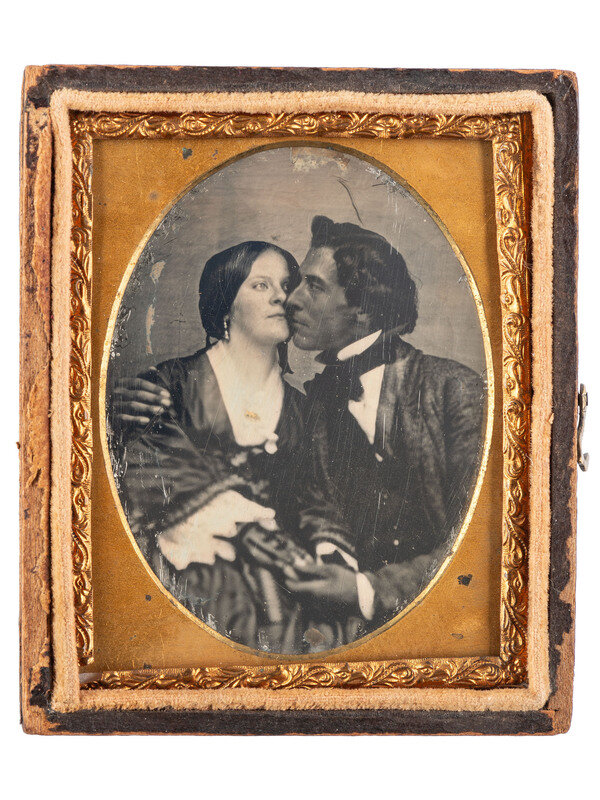

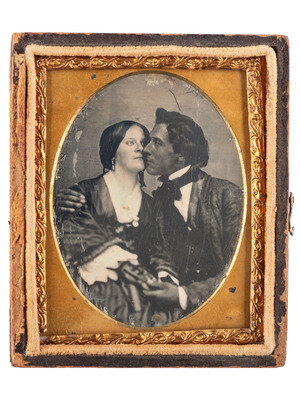

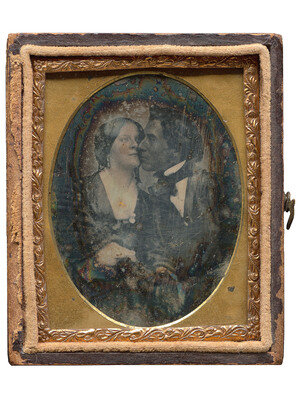

[EARLY PHOTOGRAPHY]. A remarkable ninth plate daguerreotype of an interracial couple.

Sale 2057 - American Historical Ephemera and Photography

Oct 25, 2024

10:00AM ET

Live / Cincinnati

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$30,000 -

50,000

Price Realized

$20,320

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

[EARLY PHOTOGRAPHY]. A remarkable ninth plate daguerreotype of an interracial couple.

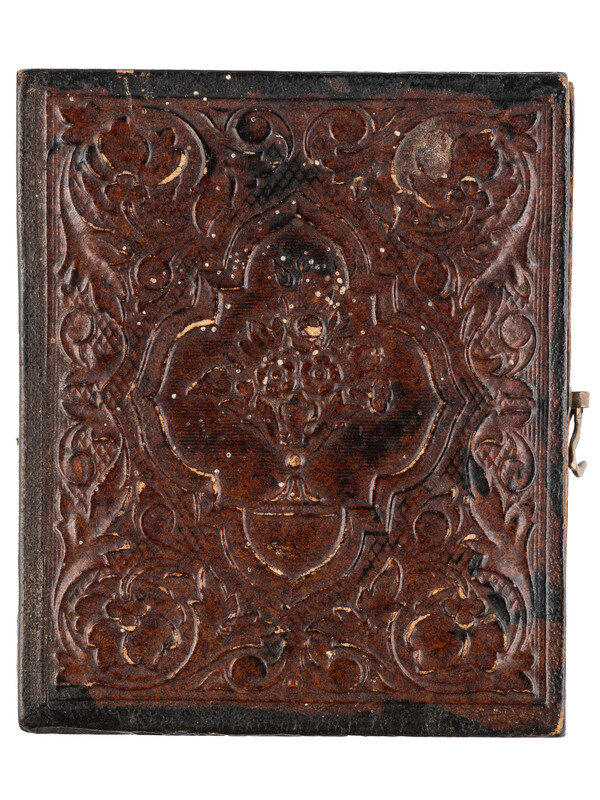

Anonymous, ninth plate daguerreotype, ca 1850-1855 depicting a white woman and African American or mixed-race man in an amorous pose, his arm draped around her shoulder, pulling her close while they hold hands. As of this writing we have been unable to locate another daguerreotype of a black man and white woman in an overtly romantic display. Was the portrait a political statement, a token of love, or both? And why the small plate size when the standard of the day was the sixth plate, an image twice as large? Who took the image?

In the turbulent years prior to the Civil War, a photograph of a white woman and an African American man even hinting at a romantic relationship would have been scandalous, and in some areas, dangerous. By having their photograph taken in such an unmistakable pose, the couple was consciously flaunting legal and social proscriptions of the day.

We believe the purpose of the image was likely political, though this is far from certain. Many abolitionists publicly and privately expressed belief in interracial love, romance and even marriage, but laws prohibiting “amalgamation” were widespread in both the North and South. Between the founding of the Republic and the outbreak of the Civil War, no less than 28 states and several Indian nations passed laws forbidding interracial marriage and interracial sex (Pascoe 2009-20-21).

It is probably no coincidence that where abolitionism was strongest – New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and the rest of New England (except for Maine) – such laws were never enacted. Yet even those with strongly held sentiments about racial equality more often than not drew the line at romance between races. In the North, state law and social prohibition served to institutionalize racism.

In the South, where legal marriage between slaves was outlawed and sexual license between master and enslaved women was taken for granted, “amalgamation” was a direct challenge to the institution of slavery itself. As long as masters were prevented from “turning slaves they slept with into respectable wives who might claim freedom, demand citizenship rights, or inherit family property” the bedrock foundations of a racialized society remained safe (Pascoe 2009:27).

A good deal has been written about the use of photography by abolitionists to further their cause (see Amato-Fox 2019 and Stouffer et. al. 2015). At a time when African Americans were often grotesquely exaggerated in prints and other media, Frederick Douglass, for example, recognized photography as a means of truth telling, and a medium that could humanize African Americans (see Stouffer et. al. 2015: X-XIII).

Douglass and his colleagues recognized, however, that for a photograph to have real, lasting power, it needed to be widely circulated. As a unique image, the daguerreotype was unsuited to widespread dissemination, and could only be exposed to a wider audience through an engraving. If this image was taken for abolitionist propaganda it seems to have never been engraved; no trace of it exists in the historical record.

To date, an attempt to identify the sitters has proven unsuccessful. Their portraits are not included, for example, in the Francis Jackson Garrison collection of nearly 750 photographs of abolitionists and fugitive slaves curated at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Assembled by William Lloyd Garrison and his family, this collection is undoubtedly the most comprehensive pictorial assemblage of the abolitionist movement.

It is useless to speculate who might have taken the photograph. By the time this image was taken, more than a decade had passed since the daguerreotype swept America after being introduced in 1839. By 1850 hundreds of daguerreian “artists” operated studios in both large and small towns, north and south. Itinerants plied their trade via horse-drawn traveling studios (Newhall 1964: 47). Several daguerreotypists, black and white counted themselves as abolitionists. Any one of them – or even another artist – could have taken the photograph.

In a world where racial stereotypes denied the humanity of blacks and the notion that they were incapable of the same emotions as whites, this image stands alone. Posed or not, the message of this small treasure is clear: in matters of the heart, white and black could be equal partners. It is hoped that by exposing this image to a wider audience, the identifies of the sitters will be discovered. Their names are almost certainly the key to placing the image into wider social and historical context.

Provenance: Found in the estate of Stephen Cline of Ashland, New York. Cline apparently had been an antiques dealer in New York City from the 1960s through the 1980s and moved upstate after being estranged from his family for his participation in the Stonewall Riots of the late 1960s. After his death the image was found among his effects and was purchased by the present owner at auction in 2012.

References Cited

Amato-Fox, Matthew

2019 Exposing Slavery. Photography, Human Bondage and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America. Oxford University Press.

Massachusetts Historical Society

2024 Portraits of American abolitionists, Photo. Coll. 81, Massachusetts Historical Society Photo Archives. Accessed online August 31, 2024. https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fap014

Newhall, Beaumont

1964 The History of Photography. The Museum of Modern Art. New York.

Pascoe, Peggy

2009 What Comes Naturally. Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. Oxford University Press.

Stauffer, John, Zoe Trodd and Marie Bernier

2015 Picturing Frederick Douglass. An Illustrated Biography of the 19th Centiry’s Most Photographed African. W.W. Norton Ltd.