Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

Lot 301

The Henry Fitz Jr. archive of photographic history, including one of the world's earliest surviving photographic portraits.

Sale 955 - The Henry Fitz Jr. Archive of Photographic History

Nov 15, 2021

10:00AM ET

Live / Cincinnati

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$150,000 -

300,000

Price Realized

$300,000

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

The Henry Fitz Jr. archive of photographic history, including one of the world's earliest surviving photographic portraits.

Archive comprised of 27 items, including 23 daguerreotypes, one tintype, one carte de visite, and oil paintings of Henry Fitz Jr. and his wife Julia Wells Fitz.

Provenance:

Henry Fitz (1808-1863)

Julia Ann Wells Fitz (1814-1892)

George Wells Fitz (1860-1934)

Barbara Fitz Switzer (1904-1991)

Thence by descent to the present owner

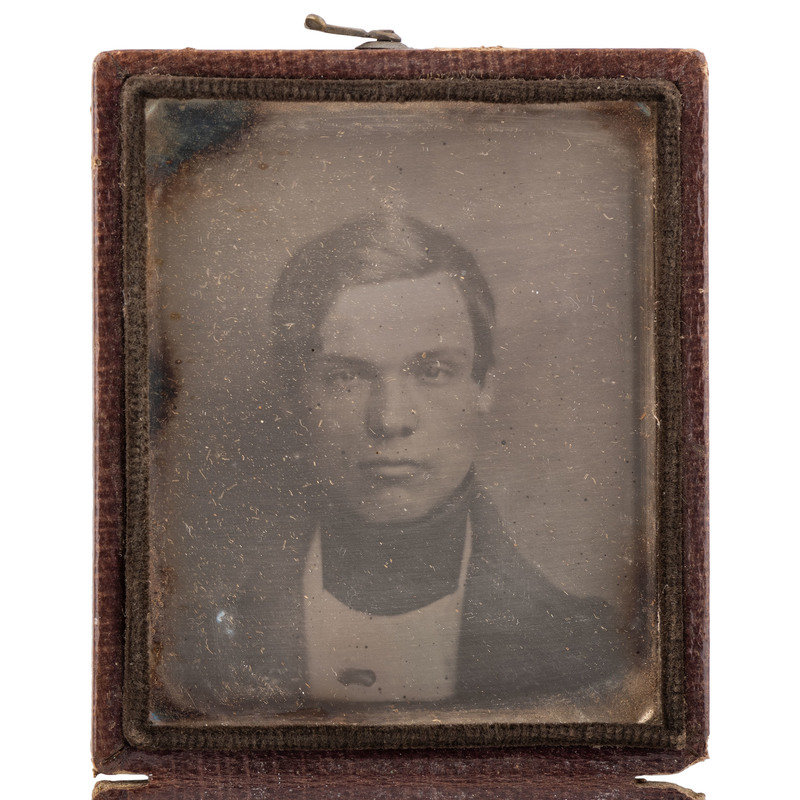

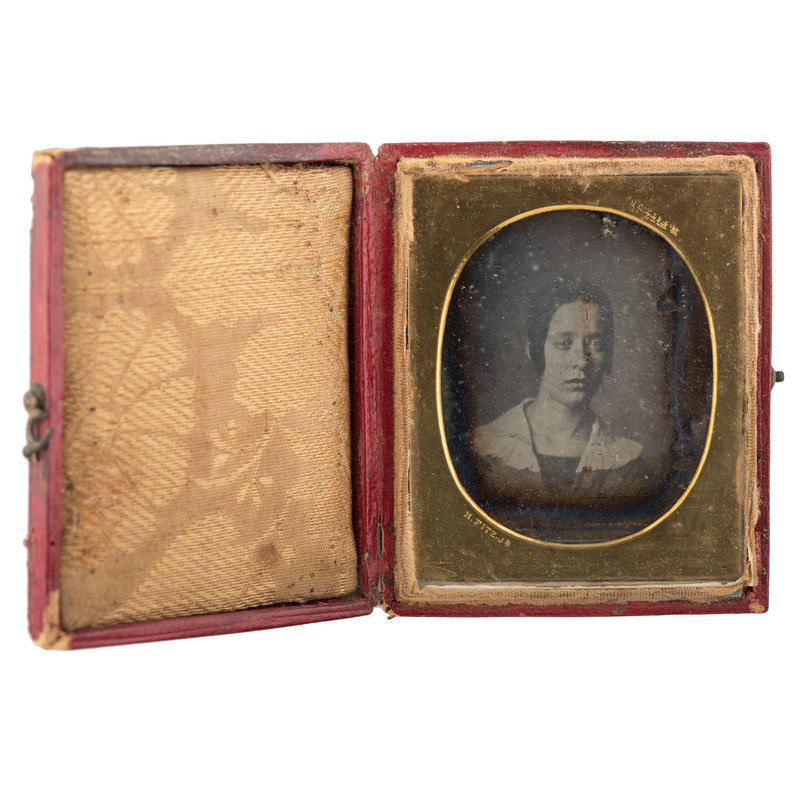

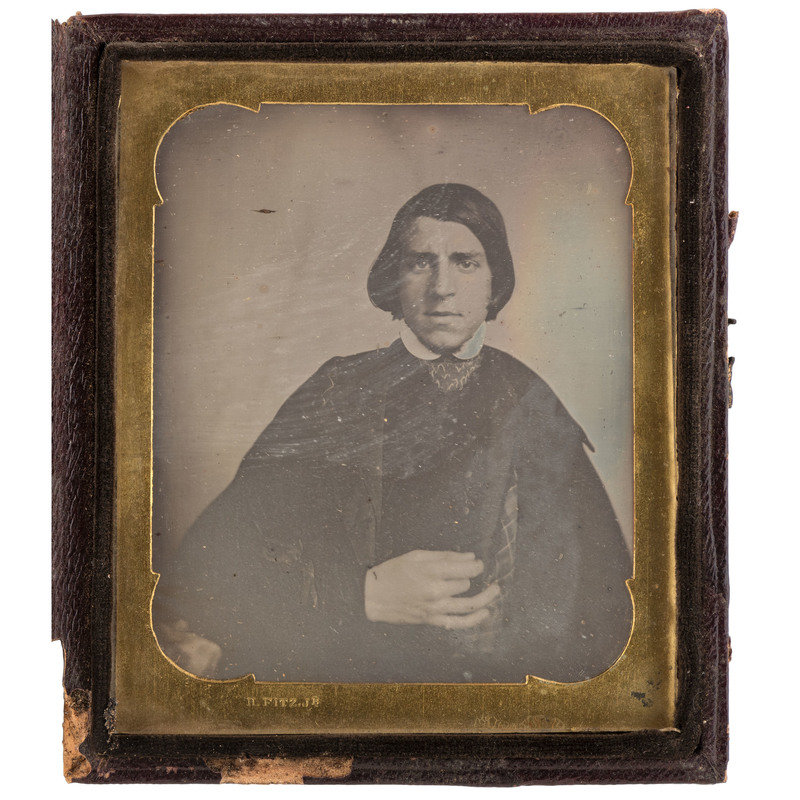

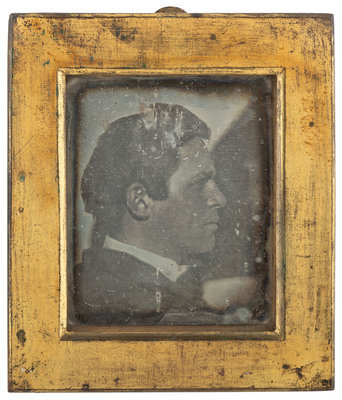

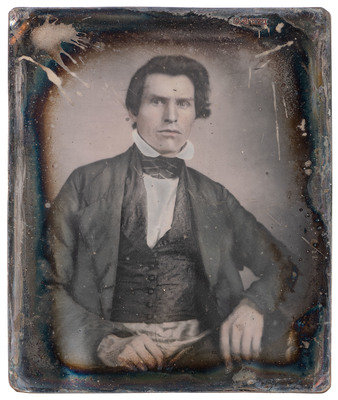

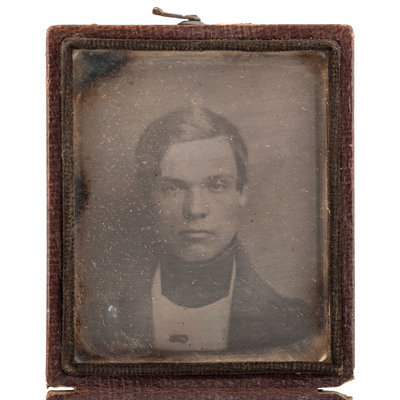

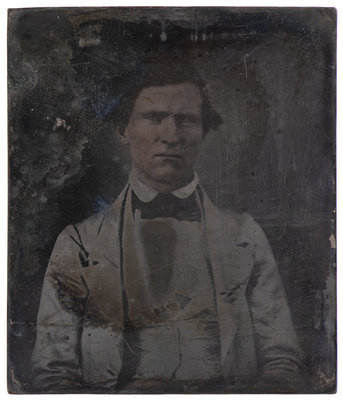

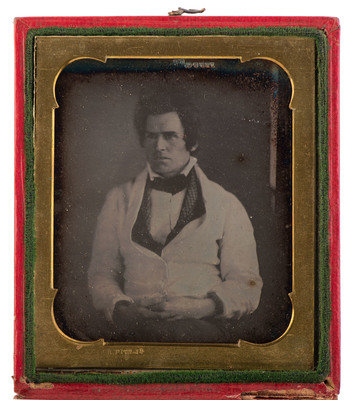

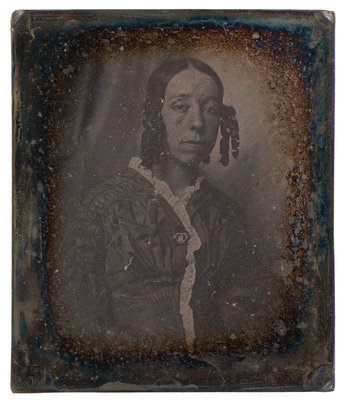

Henry Fitz Jr. (1808-1863) was among the first to conduct experiments with the daguerreotype process needed to use sunlight, optics and chemistry to make a photograph. His knowledge of optics was integral to the development of the first patented American camera and the first photographic portrait studio in America. Collaborating with two other New Yorkers (Alexander S. Wolcott and John Johnson) in late 1839 and in the first few months of 1840, Fitz sat for some of the earliest successful photographic portraits ever taken. In June of 1840 he was the first to establish a photographic studio in Baltimore, Maryland. Fitz was instrumental in the development of the technology that transformed the way in which humans perceived themselves and their place within society and culture.

Henry Fitz Jr. (1808-1863) was among the first to conduct experiments with the daguerreotype process needed to use sunlight, optics and chemistry to make a photograph. His knowledge of optics was integral to the development of the first patented American camera and the first photographic portrait studio in America. Collaborating with two other New Yorkers (Alexander S. Wolcott and John Johnson) in late 1839 and in the first few months of 1840, Fitz sat for some of the earliest successful photographic portraits ever taken. In June of 1840 he was the first to establish a photographic studio in Baltimore, Maryland. Fitz was instrumental in the development of the technology that transformed the way in which humans perceived themselves and their place within society and culture.

The cache of daguerreotypes offered here – along with the existing Fitz group at the National Museum of American History – is the largest group of images produced by a single photographer from the pioneering era of photography in America (1839-1842). In this regard it is unique. While single images from this period exist, most are anonymous, undated and orphans floating in the historical ether. By contrast, the Fitz archive can be quite tightly dated to have been produced between about January 1840 and the fall of 1842. It was during these 36 months that photography in America sprang to existence and emerged as a commercial enterprise.

The Fitz daguerreotypes are prima facie evidence of the first months of development of photography in America, and even more importantly the search for making portraits. This was a time of experimentation, when learned men used their knowledge of chemistry, physics, light, and optics to develop a technology that would change the world. Not since the Feigenbaum collection of Southworth and Hawes images surfaced has a similar collection come to light. At a time when “chemical” photography has by and large given way to a “digital” medium, these images form a body of historically important images worthy of preservation as a collection.

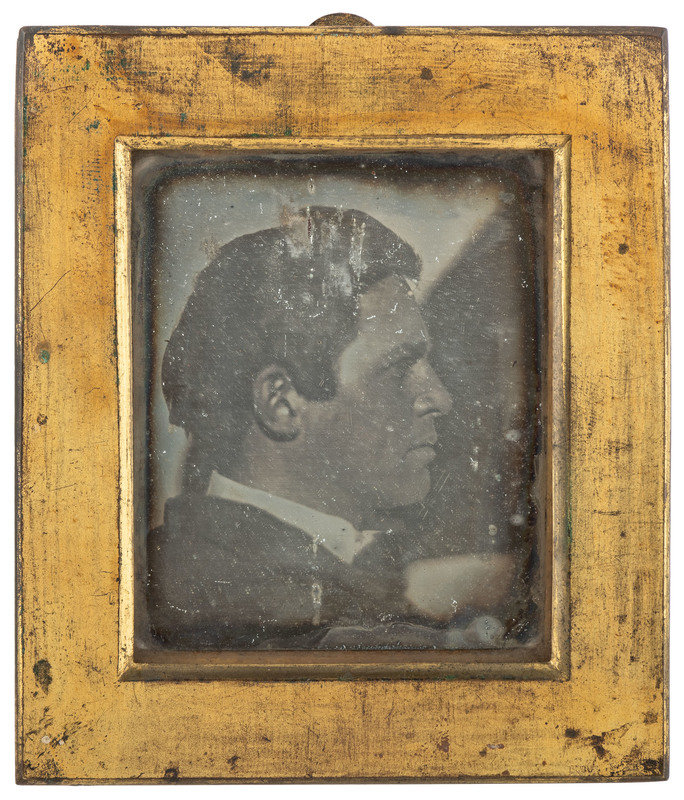

Beginning in 1930, Fitz’s son Harry opened a dialog with the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution which lasted nearly a decade. Between 1930 and 1939 when Harry died, the contents of the Fitz telescope shop, a camera (claimed erroneously by Harry, to have been used to take the first portrait in America), various photographic equipment and 22 daguerreotypes were donated to the National Museum of American History. Among the images received by the Department of Photographic History was a primitive “eyes closed” portrait of Henry Fitz Jr., which has often been reproduced and asserted to be one of the earliest self portraits taken in America (Foresta and Wood 1995:38; Newhall 1961, Figure 2; Welling 1987:13).

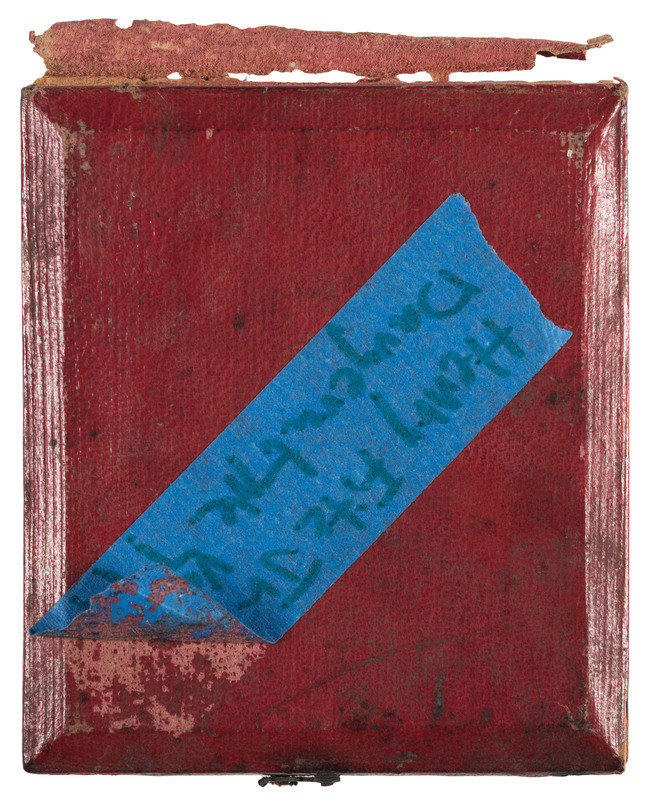

Throughout his correspondence with the Smithsonian, Harry mentioned other Fitz artifacts that were held by his brother George W. Fitz. The Museum tried to acquire this additional material but letters to George went unanswered. When George died in 1934, no gift had been consummated. Now, 87 years after the last contact with the Smithsonian, George’s archive has finally come to light, discovered in his unheated, un-air-conditioned office and workshop in Peconic, New York.

THE FIRST DAGUERREOTYPES IN AMERICA: EXPERIMENTS IN NEW YORK CITY

THE FIRST DAGUERREOTYPES IN AMERICA: EXPERIMENTS IN NEW YORK CITY

In March 1839 the American painter and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse wrote from Paris to his brothers in New York describing a visit to the studio of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. Daguerre had, that day, shown Morse some of the world’s first photographs – street scenes and still life studies -- fixed on silvered copper plates in such astonishing detail that the exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived (Morse, 1839, as printed in the New York Observer). The exposure time required to take a picture was measured in minutes. When Morse asked about the possibility of using the invention for portraits, Daguerre reportedly expressed doubts that his device could accomplish such a feat (Taft 1937:22-23).

News of the discovery circulated widely, but it was not until August 1839 when the French government purchased Daguerre’s invention and he revealed the secrets of the process. Not long after, a manual specifying the steps needed to produce daguerreotypes was published in multiple languages and became an international best-seller.

An early French version of the manual was rushed to New York by an Englishman, D.W. Seager, who produced what might have been the first daguerreotype in America -- a picture of St. Paul’s Church taken on or about September 27, 1839. News of Seager’s picture was published in The New York Morning Herald on September 30 (Ibid). Like Daguerre’s early images, Seager’s picture was of an inanimate object. The long exposure time necessary to produce an image on a plate allowed for little else.

WOLCOTT’S MIRROR CAMERA: ENTER HENRY FITZ JR.

After the announcement of his success, Seager held a lecture describing the daguerreotype process in detail on October 5th. The next day, John Johnson delivered the news to his partner Alexander Wolcott, a manufacturer of dental equipment and instruments. That afternoon Wolcott put pencil to paper and designed and built a prototype for a camera using a speculum (a polished metal mirror used in optical devices). This was a significant innovation. Wolcott’s mirror camera delivered more light to the sensitive plate than Daguerre’s camera which relied on a glass lens, thus reducing exposure time.

Following a series of trials in the attic of Wolcott’s home that same day, the pair succeeded in making a 3/8” square profile portrait of Johnson. The exposure time was five minutes (Johnson 1846:8). Sadly, this image has not survived, but it may have been the earliest photographic portrait taken in America, if not the world.

Even this miniscule daguerreotype was a breakthrough, and the beginning of the search for the holy grail: photographic portraits of living beings. Before the advent of photography, the most common medium for capturing one’s likeness was a watercolor or oil painting, either small scale on sheets of ivory or paper, or on a larger canvas or wood panel. In either case, this type of portraiture was beyond the financial reach of the average American; a painted portrait was the privilege of the wealthy. A daguerreotype of a church steeple was a small miracle, but portraiture was where the money was. It didn’t take long for Wolcott and Johnson to recognize that if they could produce portraits via their mirror camera, financial riches would follow. The race was on.

With this goal surely in mind, the pair set about the task of creating larger portraits and shortening the time of exposure. No one could be expected to sit still for five minutes. The problem, as they saw it, was that Daguerre’s original device used a lens that could not deliver enough light to the sensitized silvered plate. Their first mirror camera could only focus light on a tiny area. They needed a bigger mirror.

Trial and error suggested that using an 8” speculum mirror with a focal length of 12” might do the trick. But mirrors then available needed to be altered through careful polishing to focus the light. Lacking the expertise to achieve this result, Wolcott and Johnson turned to their friend Henry Fitz Jr.

Fitz was a locksmith by trade but already gaining a reputation as a maker of telescopes. In October, at the time the first portrait with the mirror camera was made, he was in England visiting sources for telescope glass (Johnson 2015:151-153). Recent research has conclusively demonstrated that Fitz did not return to New York until December 11, 1839, and thus missed out on the early experiments (Becker 2014). Upon his return, Fitz was made aware of the predicament, and set about grinding and polishing a new mirror for the camera. Shortly thereafter, Johnson became ill, and all experiments were put off for “nearly four weeks” until early January 1840 (Johnson 1846:24). It was during this time – early January or February -- that the mirror camera apparently was perfected, and images on 2” x 2.5” plates began to be produced (Ibid).

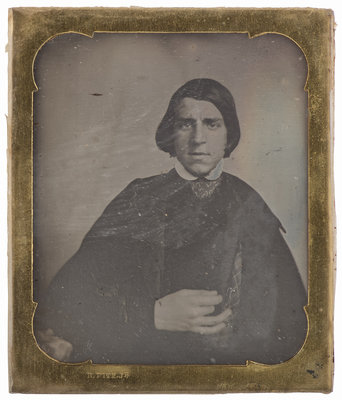

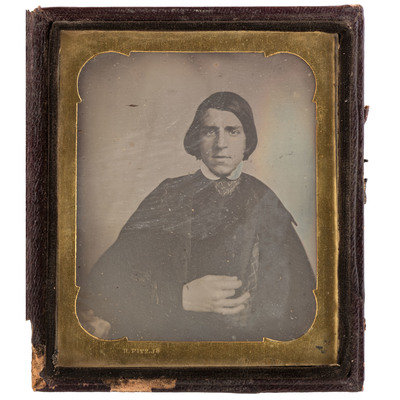

DATING THE “FITZ PROFILE” PORTRAIT

Until recently many photo-historians accepted Harry Fitz’s 1930s assertion that the “Eyes Closed” daguerreotype of his father was a self-portrait taken in the late fall of 1839. Harry’s claim is at odds with the facts.

The mirror camera capable of taking ninth plate sized portraits wasn’t available until sometime after December 11th when Fitz returned from his European sojourn and ground the necessary mirror used to

concentrate light upon the silver plate (Becker 2014).

concentrate light upon the silver plate (Becker 2014).

By his own account, all work on the camera was paused for part of December while Johnson was ill and did not resume until early January 1840 (Johnson, 1846: 24).

By early January 1840 “our experiments were again resumed with improved results, so much so as to induce Mr. Wolcott and myself to entertain serious thoughts of making a business of the taking of

likenesses from life… (Ibid).

likenesses from life… (Ibid).

By February 1840 Henry Fitz’s father was shown a daguerreotype portrait of his son and wrote:

“My son has recently shown to me a perfect miniature likeness (of the large miniature size) of himself; (i.e., a bust,) obtained by a new process of modification of reflected light, (according to the principle of Dioptrics) on metallic plates; a likeness so perfect, so incomparably above the painters art that it imbodies the living-expression of the countenance.

This truly wonderful, and astonishing effect is caused by the light of Heaven, or the Sun; reflected from a metallic reflector (received from the face of the person sitting for his likeness, on the reflector; and then transmitted) to a prepared metallic plate, that, as it were in a moment, (only one minute and fifteen seconds!! Being required,) is permanently impressed with the perfect image of the person!” (Fitz, 1840, 2:316, as quoted in Becker, 2014:214-215; emphasis in the original).

“My son has recently shown to me a perfect miniature likeness (of the large miniature size) of himself; (i.e., a bust,) obtained by a new process of modification of reflected light, (according to the principle of Dioptrics) on metallic plates; a likeness so perfect, so incomparably above the painters art that it imbodies the living-expression of the countenance.

This truly wonderful, and astonishing effect is caused by the light of Heaven, or the Sun; reflected from a metallic reflector (received from the face of the person sitting for his likeness, on the reflector; and then transmitted) to a prepared metallic plate, that, as it were in a moment, (only one minute and fifteen seconds!! Being required,) is permanently impressed with the perfect image of the person!” (Fitz, 1840, 2:316, as quoted in Becker, 2014:214-215; emphasis in the original).

About the same time, mindful that sooner or later news of their success at capturing portraits would leak out to potential competitors, the pair sent Johnson’s father, William S. Johnson “with a few likenesses” to London in early February 1840, to seek an English patent for the mirror camera (Welling 1978:18).

We can assume that these “few likenesses” were probably relatively sophisticated images, otherwise

Johnson would have had little success securing the necessary patent. After all, he had to present

something that worked. A primitive profile image might have been convincing, but surely a plate featuring

the sitter looking at the camera would have been better.

We can assume that these “few likenesses” were probably relatively sophisticated images, otherwise

Johnson would have had little success securing the necessary patent. After all, he had to present

something that worked. A primitive profile image might have been convincing, but surely a plate featuring

the sitter looking at the camera would have been better.

By March Wolcott and Johnson had opened a New York City studio equipped with mirror cameras and the associated necessary reflectors and backgrounds. Located in the Granite Building at the corner of Chambers Street and Broadway, this was the first photographic gallery in the world. Root (1868:353-354) reports the Philadelphian and early daguerreotypist Robert Cornelius visited Wolcott and Johnson in April 1840 and saw first-hand how they were using the mirror camera to make portraits.

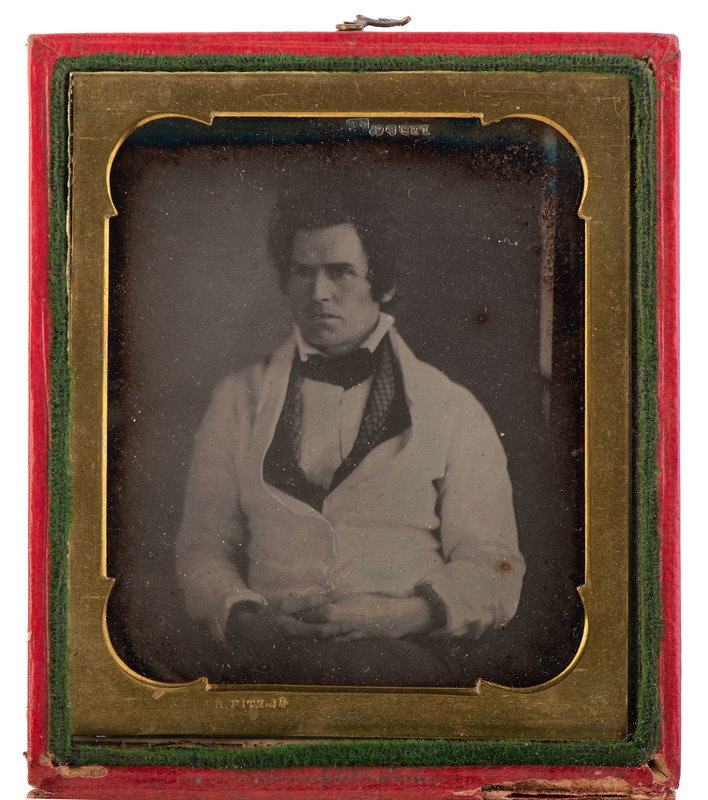

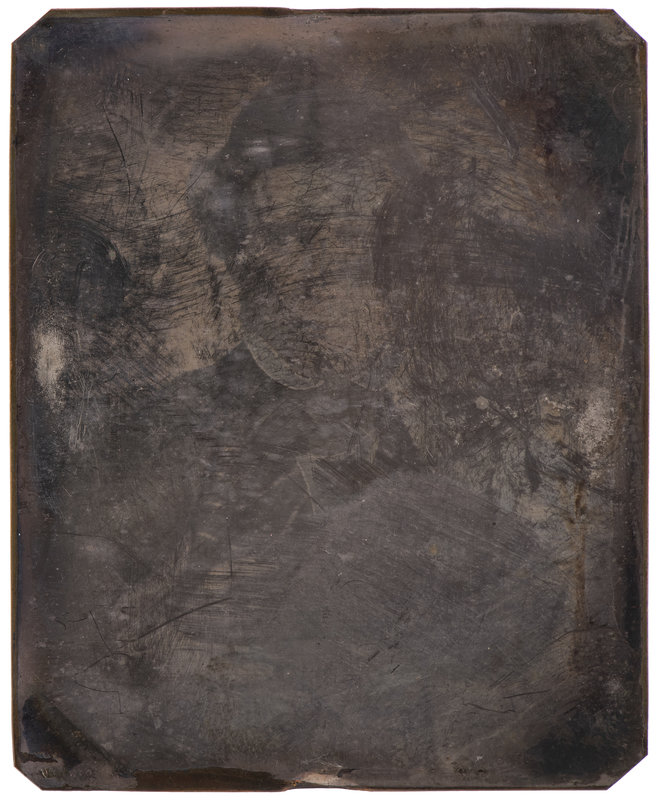

Given this history, and coupled with their primitive nature, the “Fitz Profile” and “Eyes Closed” portraits were almost certainly made in the first few weeks of January 1840. Johnson’s description of successes early that month, Fitz’ father’s description of seeing a “perfect miniature likeness” in February, and the attempt to patent the camera by the first week of February 1840 provide the linchpins for this timeframe.

Only the self-portrait taken by Robert Cornelius in Philadelphia in November 1839 and his portrait of Dr. Paul Beck Goddard taken in December of that same year are earlier. The Fitz portraits are among the earliest surviving photographic portraits in the world.

TIMELINE

1839

May 18 - News of the daguerreotype process printed in the New York Observer.

August - Daguerre’s manual is released to the world.

September 27 - D.W. Seager makes an image of St. Paul’s Church, New York city.

October 5 - Seager describes the process in a public lecture.

October 6 - Wolcott and Johnson build a camera and take the first photographic portrait in America.

October 21 - Henry Fitz writes from England discussing his search for quality telescope glass.

October/November - Wolcott and Johnson continue experiments.

December 11 - Fitz returns from Europe and is enlisted by Wolcott and Johnson to grind a mirror for their improved camera.

December - Wolcott falls ill and is unable to continue experiments until early January 1840.

1840

January 1 - Johnson reports the improved mirror camera is used to make ninth plate sized portraits.

Early to mid January - The “eyes closed” and “profile” views of Henry Fitz are taken with the mirror camera.

Early February - Henry Fitz Sr. reports seeing a likeness of son Henry Fitz Jr.

Early February - Johnson’s father embarks to England to patent the mirror camera, taking with him “suitable likenesses” to promote the camera’s ability.

March - Wolcott and Johnson open the first portrait studio in the world in the Granite Building, New York City.

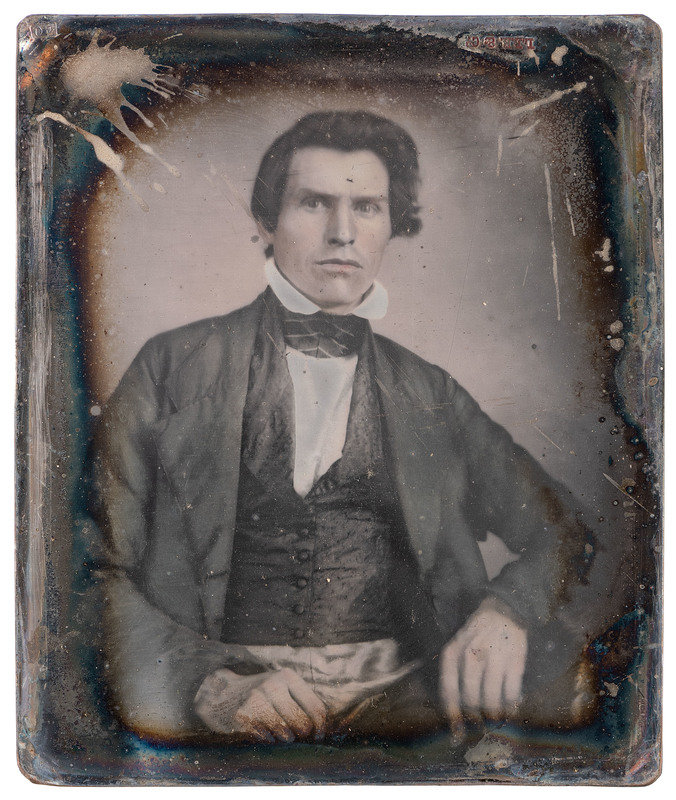

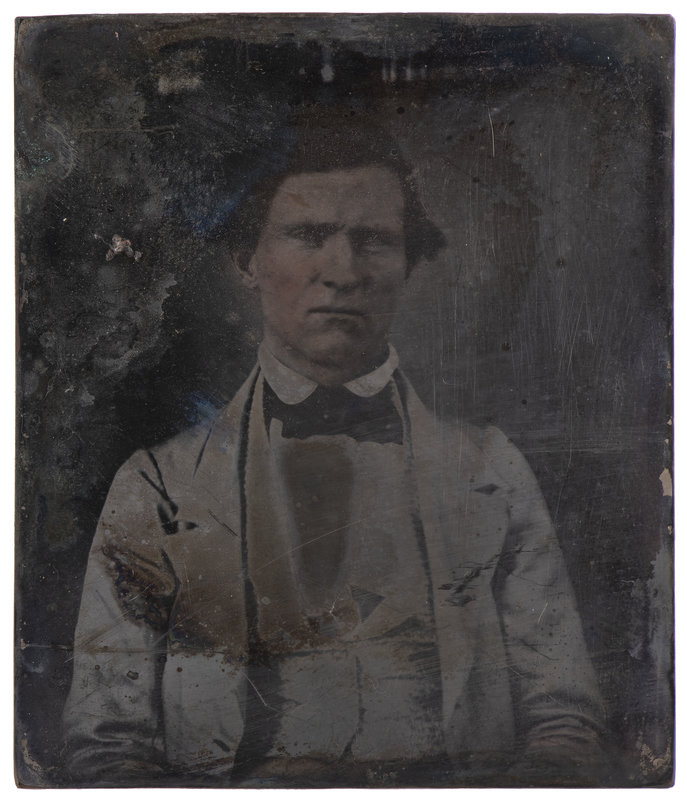

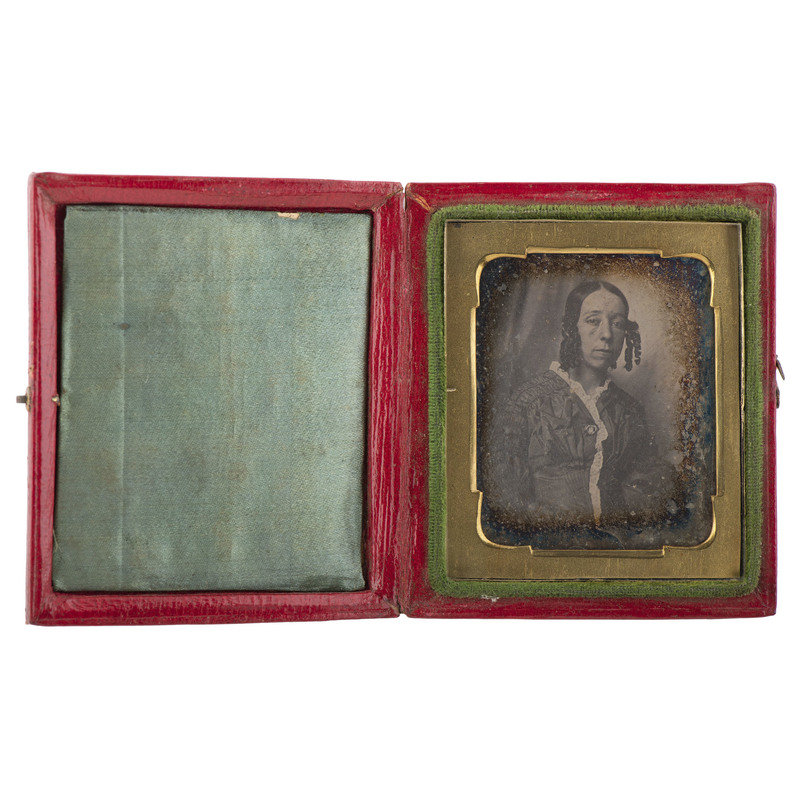

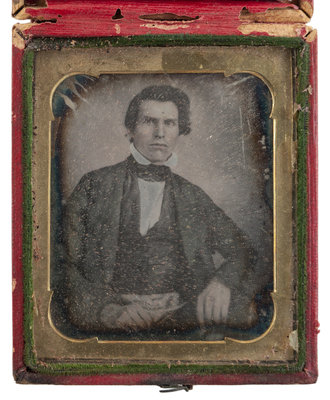

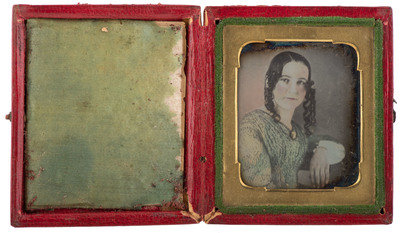

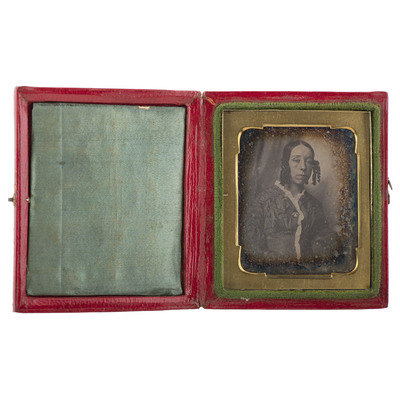

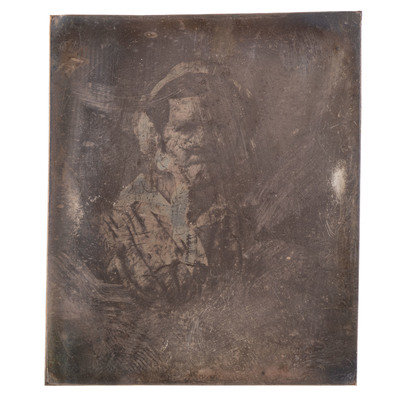

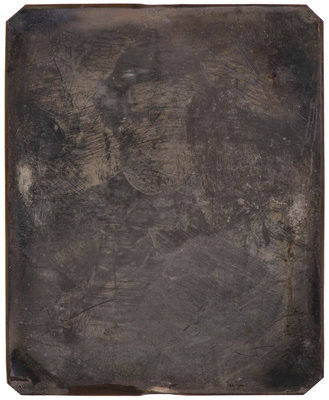

THE EARLY WOLCOTT-JOHNSON-FITZ PORTRAITS

In a real sense these pioneering photographs are the best evidence left of the first attempts at taking portrait photographs. An even casual study of these early images is key to understanding the difficulties that the Wolcott-Johnson-Fitz trio faced when trying to fix the human visage on a silvered plate.

The “Eyes Closed” portrait of Fitz exemplifies one of the issues that had to be resolved. Sunlight cast by the mirror used in the process was so intense that frontal portraits were excruciating and had to be mitigated by various sorts of screens.

HISTORY OF THE FITZ FAMILY DAGUERREOTYPES

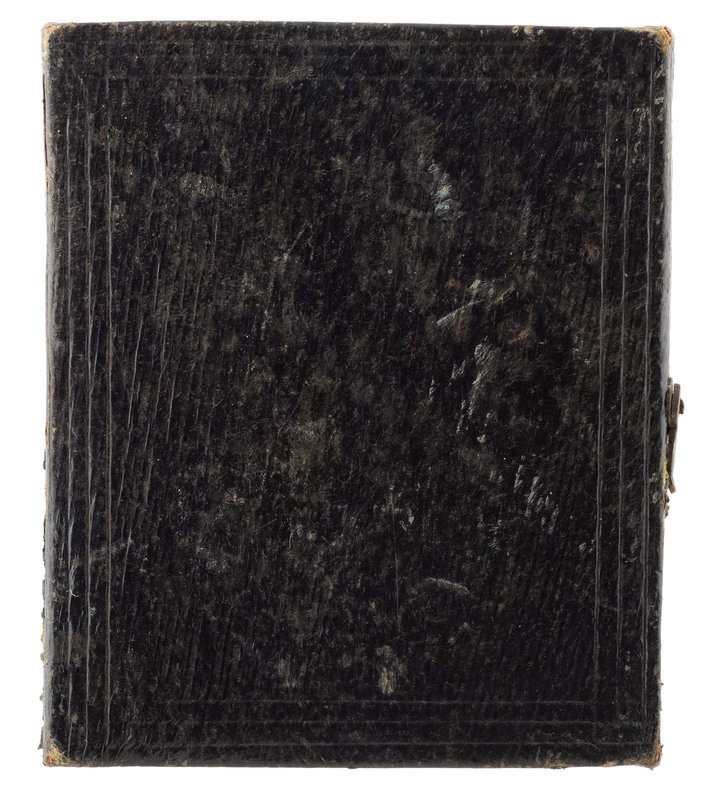

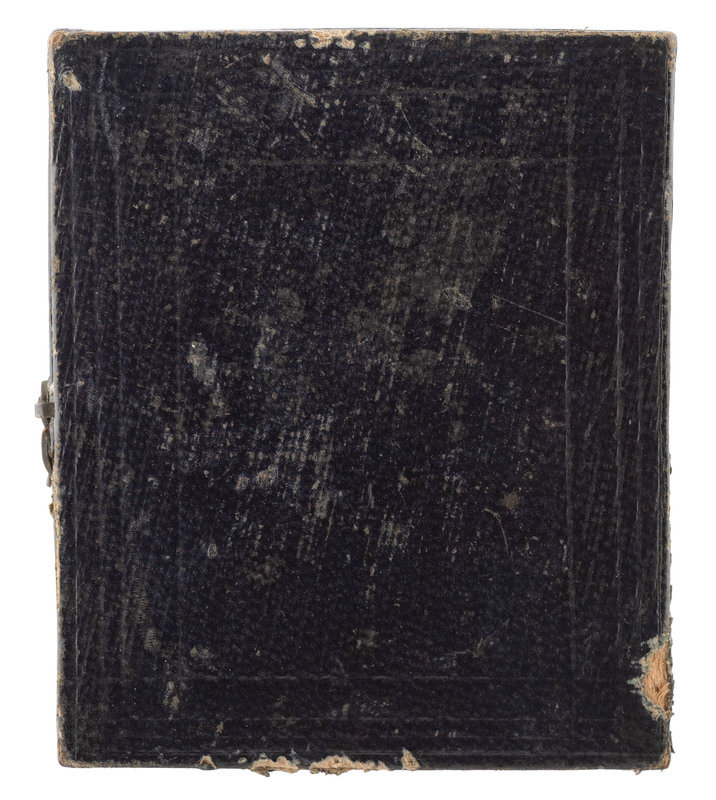

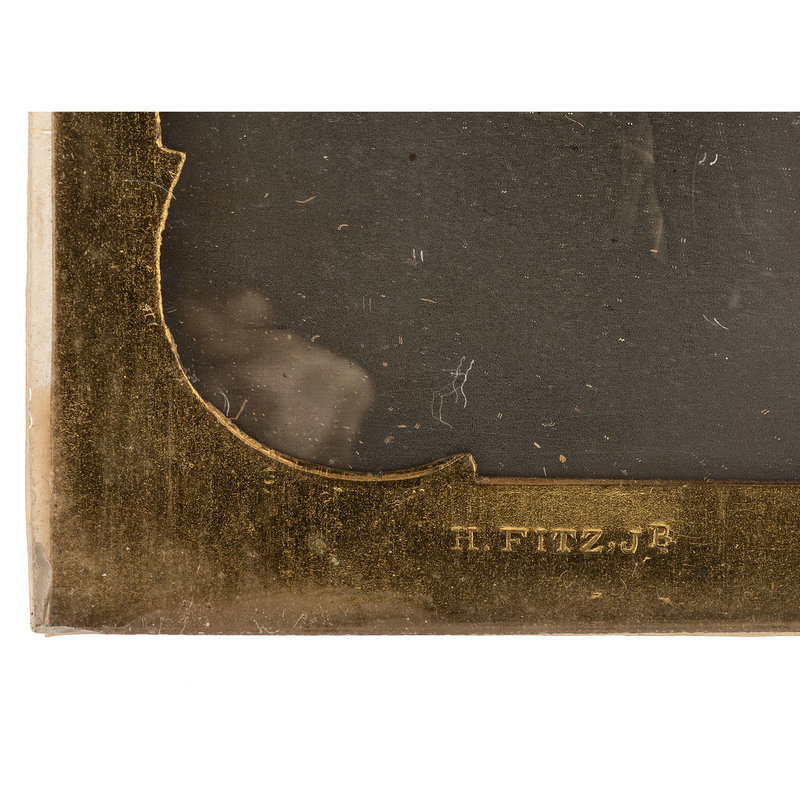

After Fitz’s collaboration with Wolcott and Johnson, he moved to Baltimore, Maryland in June 1840 and by September had established the first Daguerreian studio in that city (Kelbaugh 1998:3). His stint in the business of taking daguerreotype portraits was apparently not successful. Kelbaugh relates his price for a portrait – five dollars – was beyond the means of the average patron. No records remain of the Baltimore business, but portraits with primitive brass mats stamped H. Fitz Jr. Fecit Balt are known, and several are included in the archive of images offered here.

Fitz remained in Baltimore until late fall 1842 when he returned to New York and refocused his business efforts on manufacturing telescopes (Ibid). Over the next two decades he established a preeminent reputation, and many of his larger telescopes still survive. He died unexpectedly in 1863, killed by a falling chandelier in his Manhattan home. He left behind his widow Julia Ann Wells Fitz and six children.

Not long afterward, Julia moved the family and the Fitz business to Peconic, New York near her place of birth. The workshop was reconstituted, and their sixteen-year-old son Harry (1847-1937) ran the enterprise for the next 20 years. George Wells Fitz (1860-1934) became a doctor and was instrumental in the founding of Harvard University’s program in Anatomy, Physiology and Physical Training in 1891. After his retirement, he returned to Peconic, maintaining an office and workshop at the rear of his home overlooking Long Island sound. Harry and George survived their four siblings and were entrusted with the pioneering photographic equipment, images, and memory of their father.

The photographs and other Fitz artifacts offered here were recently discovered in an office and workshop at the residence of George W. Fitz in Peconic, New York.

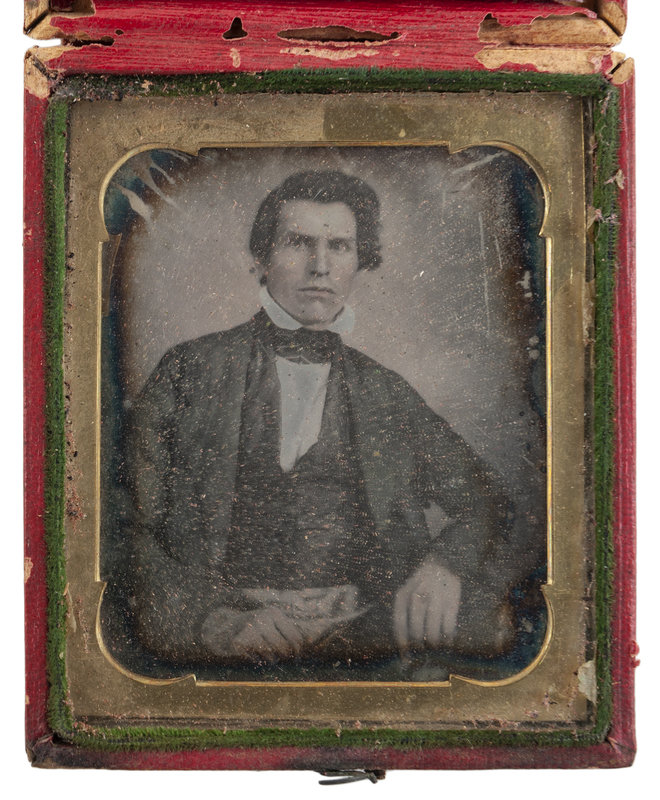

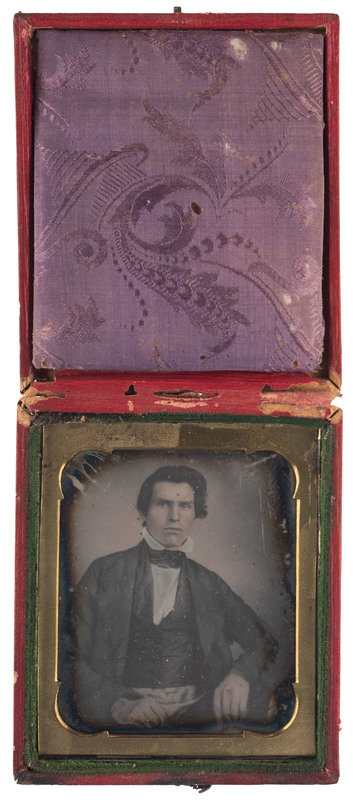

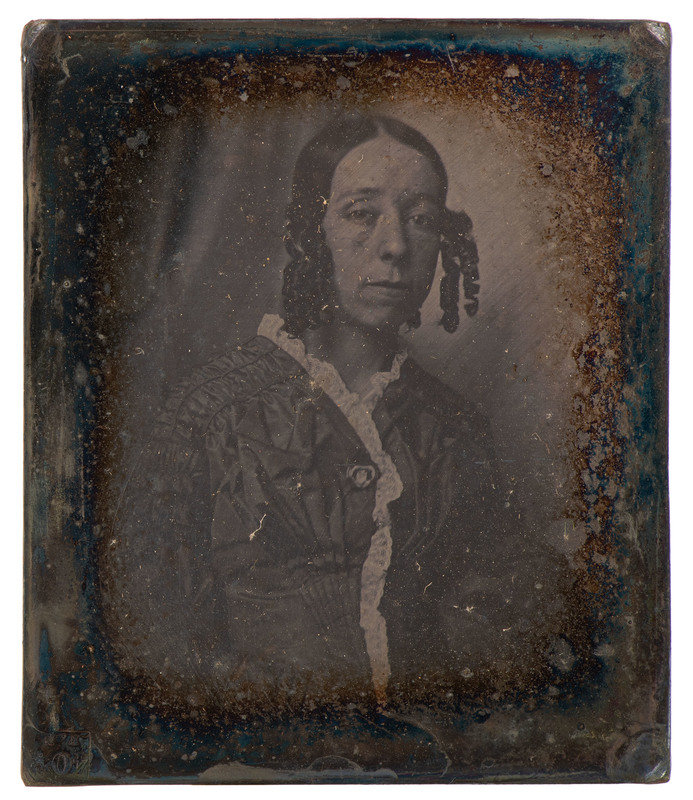

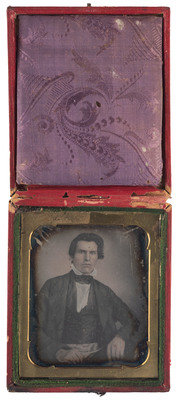

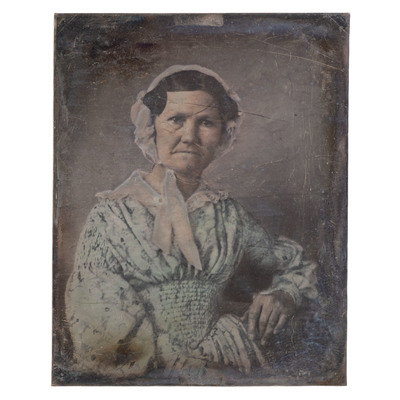

NOTES ON OTHER DAGUERREIAN IMAGES IN THE HENRY FITZ JR. ARCHIVE

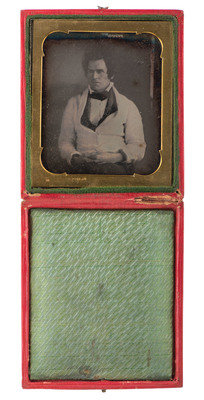

In addition to the “Profile View” of Henry Fitz Jr. discussed above, the collection includes ten ninth plate daguerreotypes and 12 sixth plate daguerreotypes. These include three, and possibly four additional portraits of Henry Fitz Jr., a portrait of his wife Julia Wells Fitz, two portraits of his sister Susan, two additional portraits thought to be of Susan, portraits of unidentified sitters, two badly damaged images of paintings, and an unused sixth plate. (NOTE: two of these last three plates are not illustrated here).

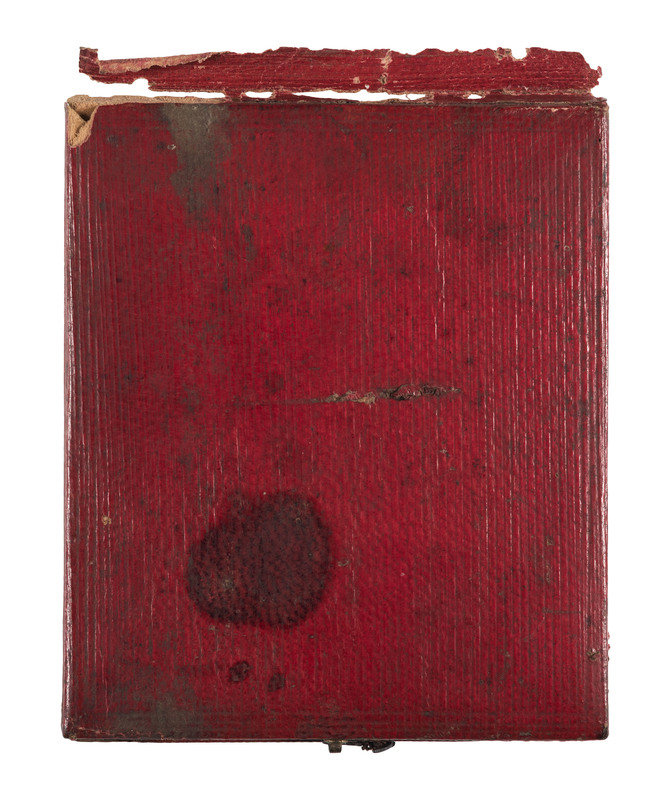

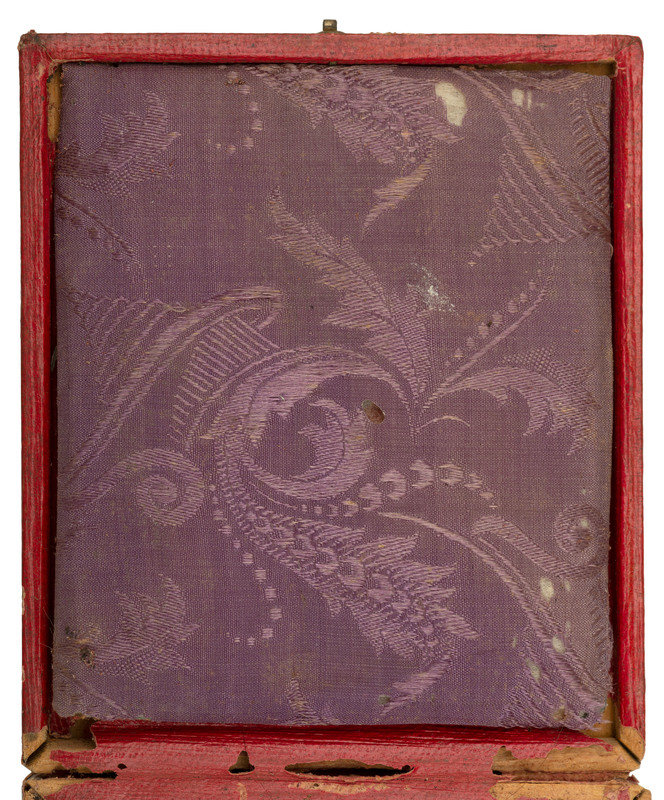

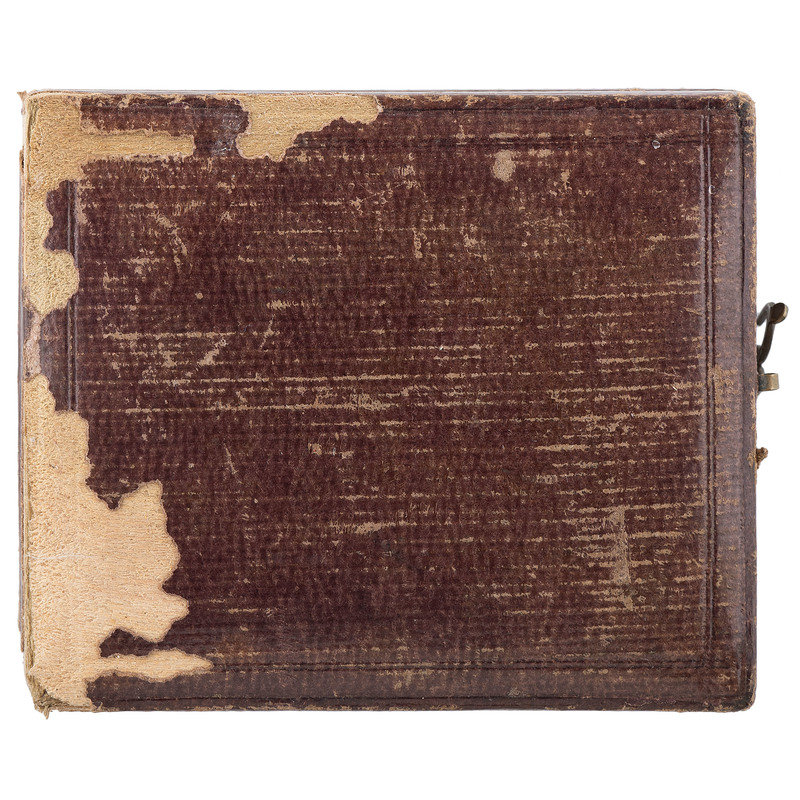

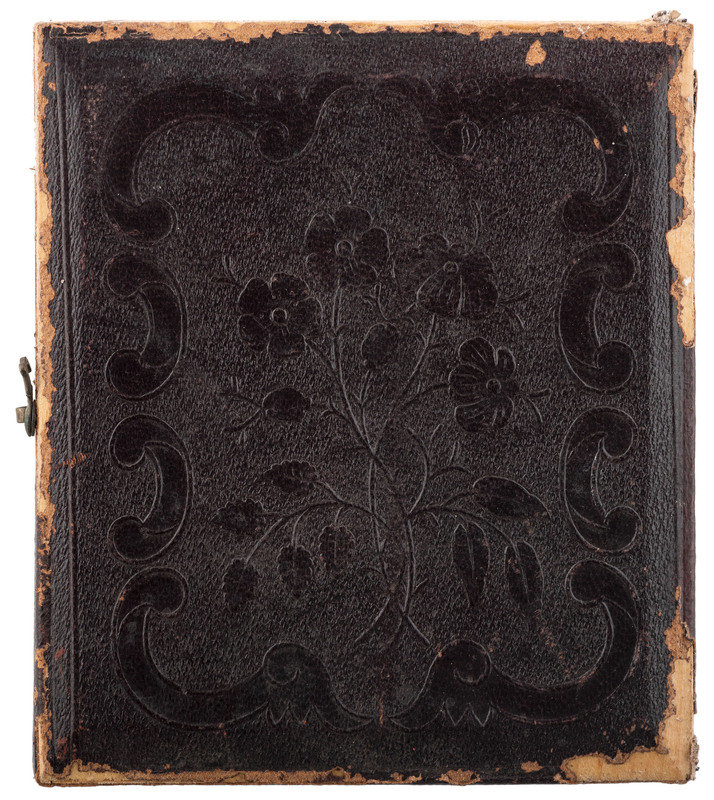

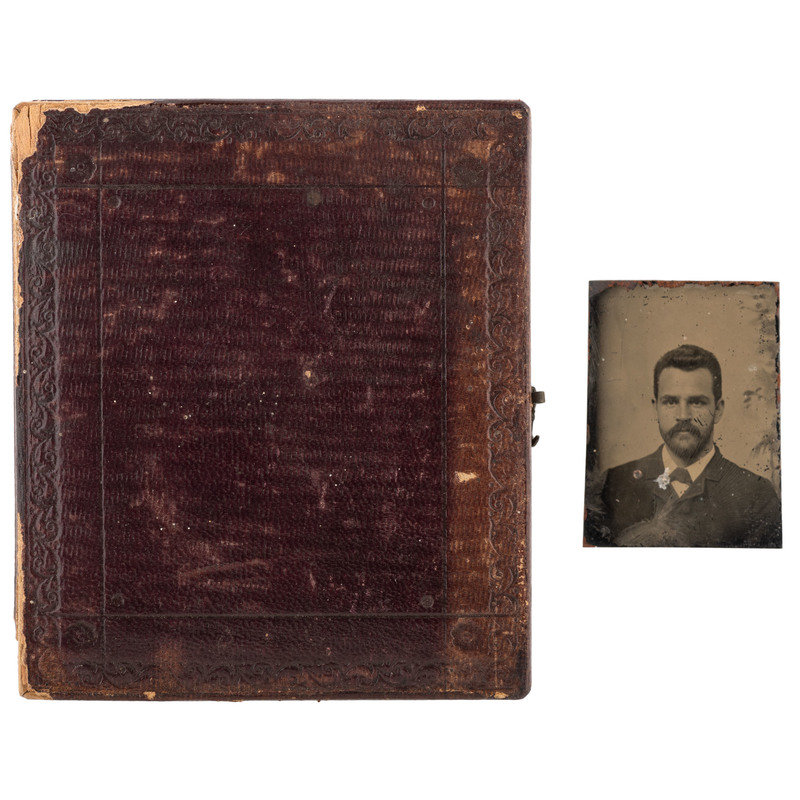

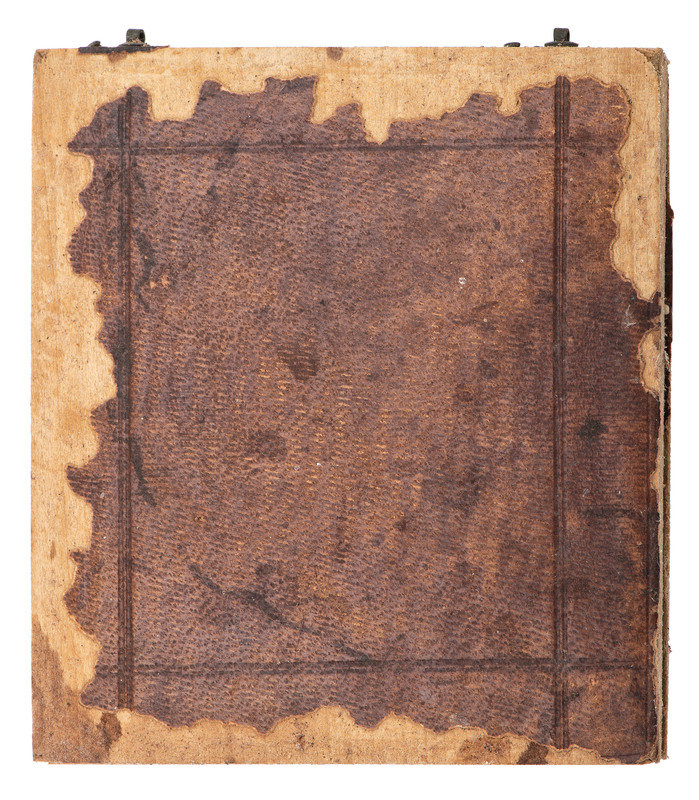

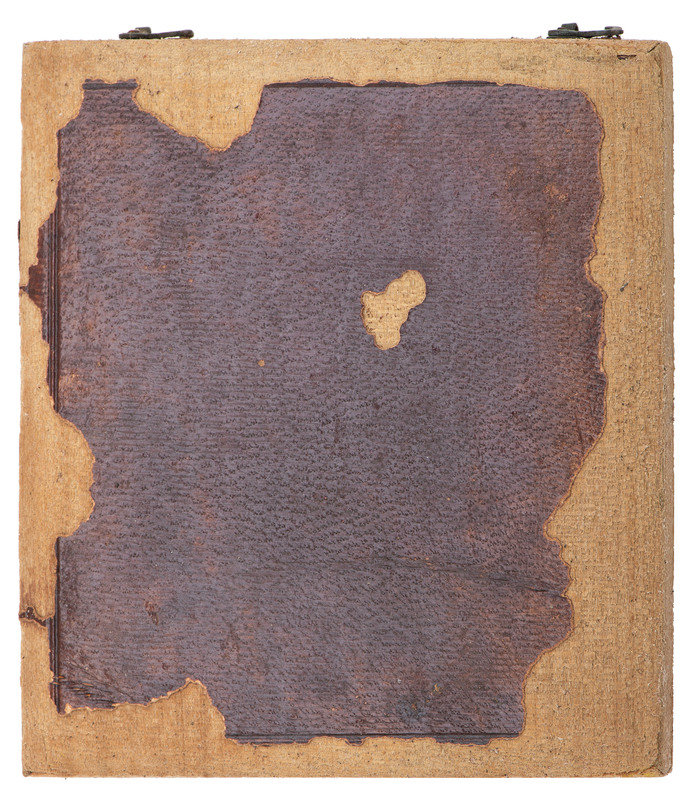

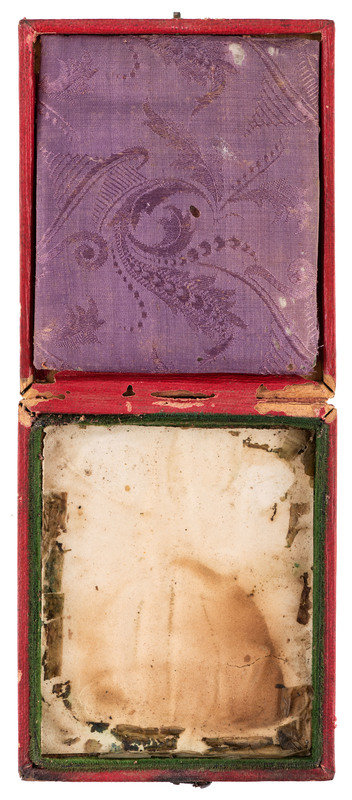

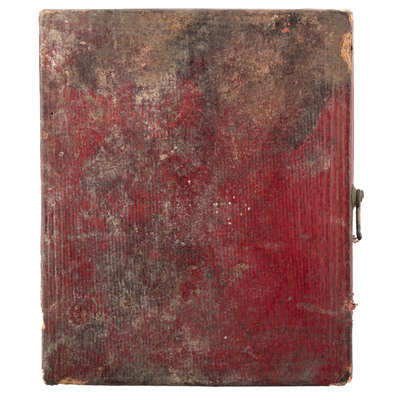

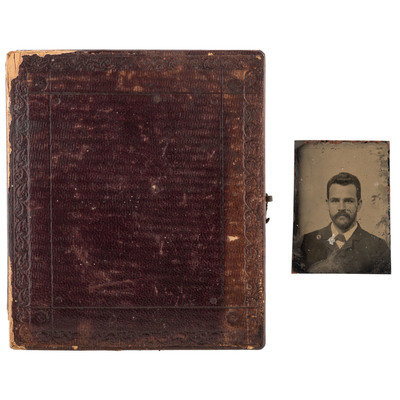

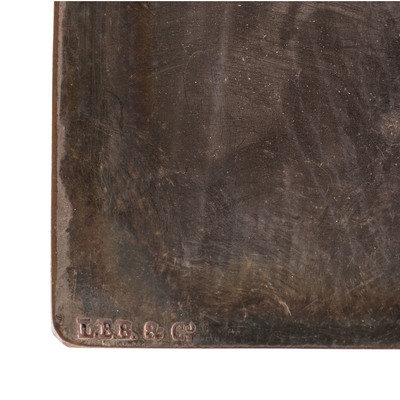

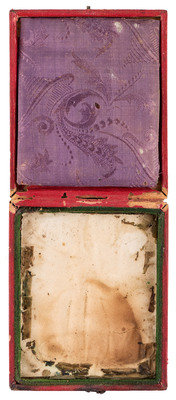

Eight of the images are encased. Three are protected by a heavy brass mat stamped either “H. Fitz Jr. Fecit Balt” or simply “H Fitz Jr” with a superscript “r.”

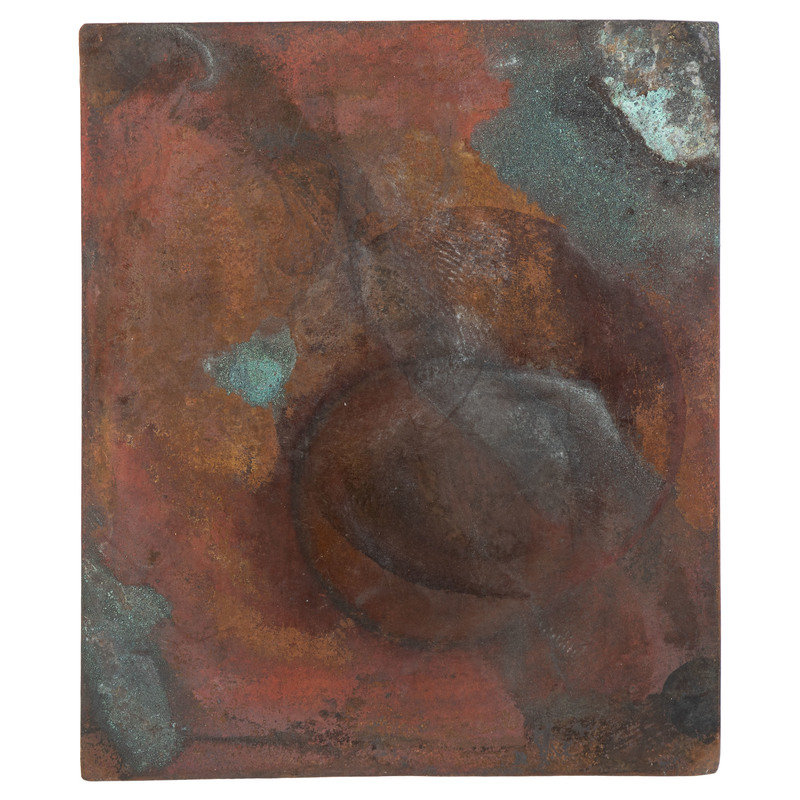

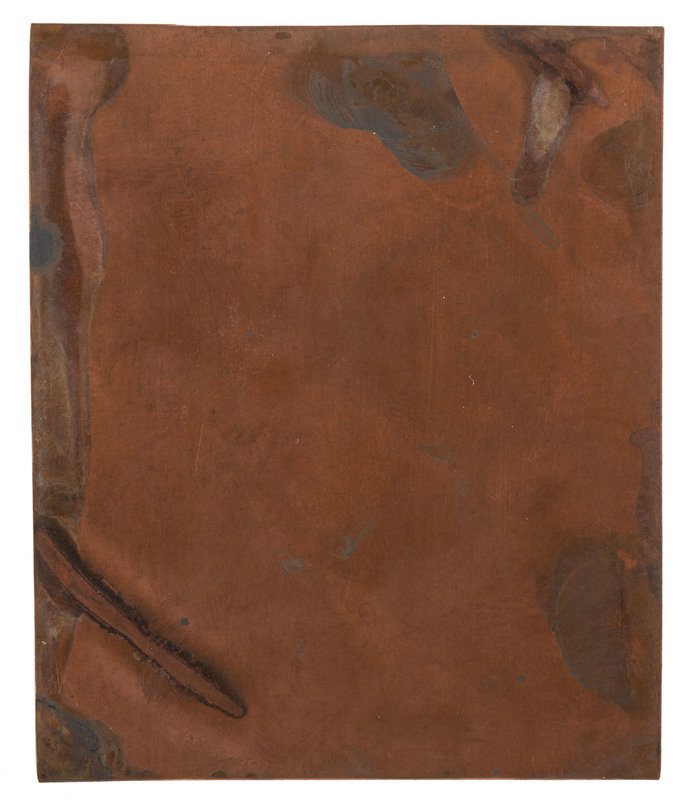

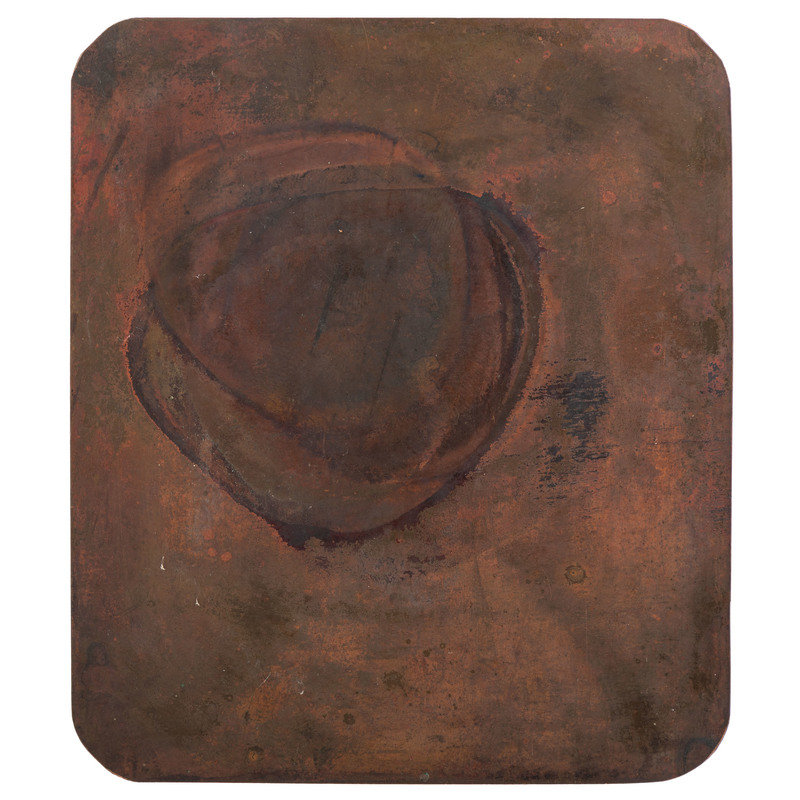

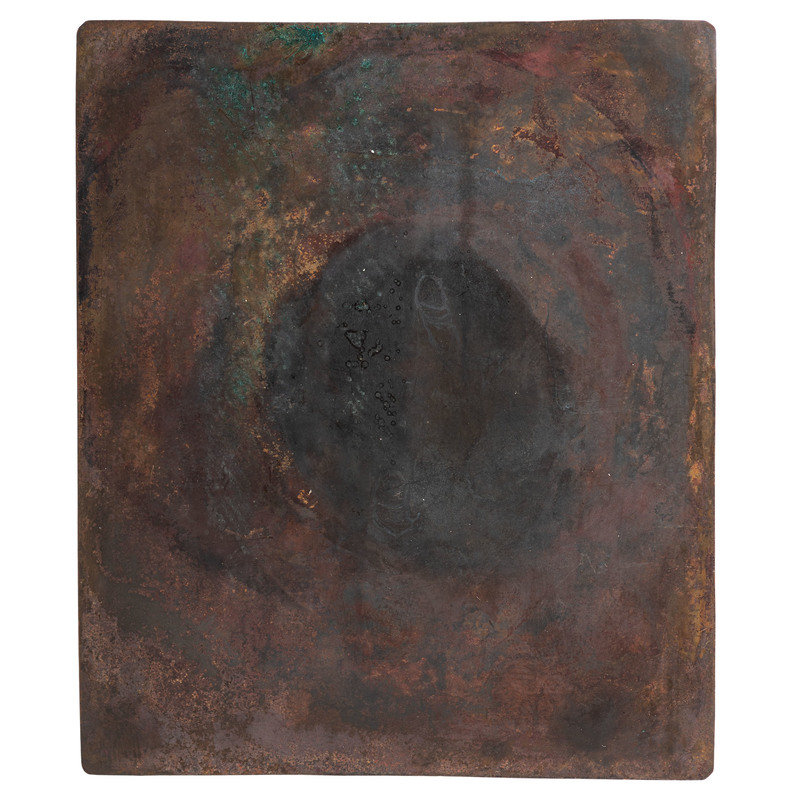

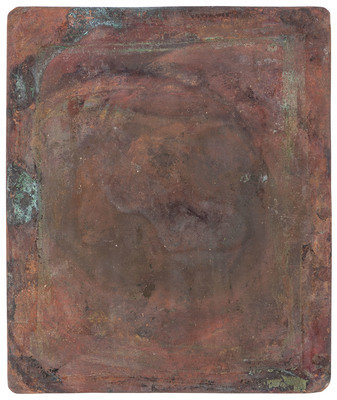

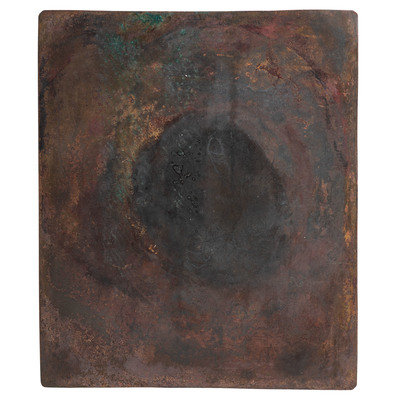

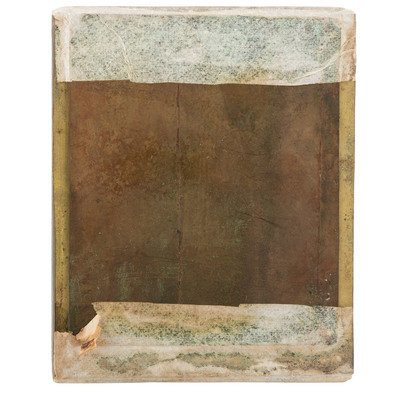

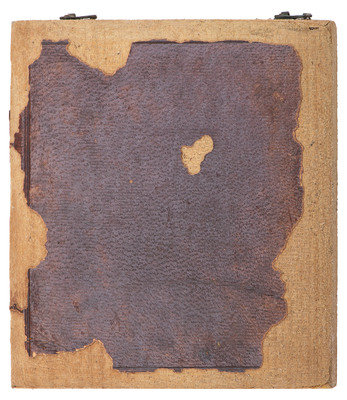

Many of the ninth plates are hand-cut from heavy, silver-plated copper. More than one is not quite square, and shows the distinctive beveled edge left by a metal shear or other cutting tool. Most have sharp, not rounded corners. Several show small, rectangular abrasions at the top and bottom center of the plate, possibly from the buffing process. The corners of virtually every plate are turned upward. Such a technique would have protected the plate from touching the mat and protective cover glass.

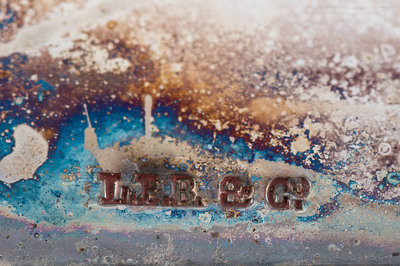

Except for four plates, all lack maker’s hallmarks. The hallmarked plates are sixth plate sized and bear three different versions of “L B B” or L B B & Co” the company of Louis B. Binsse of New York, a plate maker first identified by Newhall as “L.B. Binsse and Co., NY” (1961:161). This mark does NOT appear on the plates in the Fitz archive and are thought to be from sometime after 1843-1844. A search of New York City directories finds Binsse residing at 40 Maiden Lane in 1841-1842, and in 1841-1842 a dealer in “Fancy Articles at 34 Maiden Lane.” “Louis B. Binsse and Company” does not appear as a business name until 1843-1844, at 83 William Street. Binsse is never listed as a dealer in photographic supplies, but based upon the evidence presented here, Fitz must have used him as a supplier while he operated his Baltimore studio between 1840-1842.

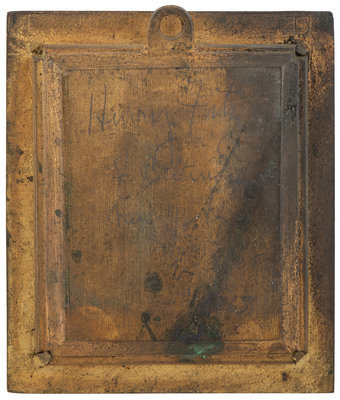

The reverse side of most of the ninth plates, and all sixth plates show clear evidence of being held over the open flame of a spirit or other lamp. Normally one would assume this to be evidence of gilding – a process of washing a solution of gold chloride across the surface of the plate to harden and amplify the image. This process was introduced in August 1840 in France but did not come into widespread use in the United States until 1842 (Rachel Wetzel, Personal Communication, July 28, 2021). Several of the Baltimore plates are hand-tinted, a process which was not possible without gilding. Other plates are quite flat and appear to be ungilded.

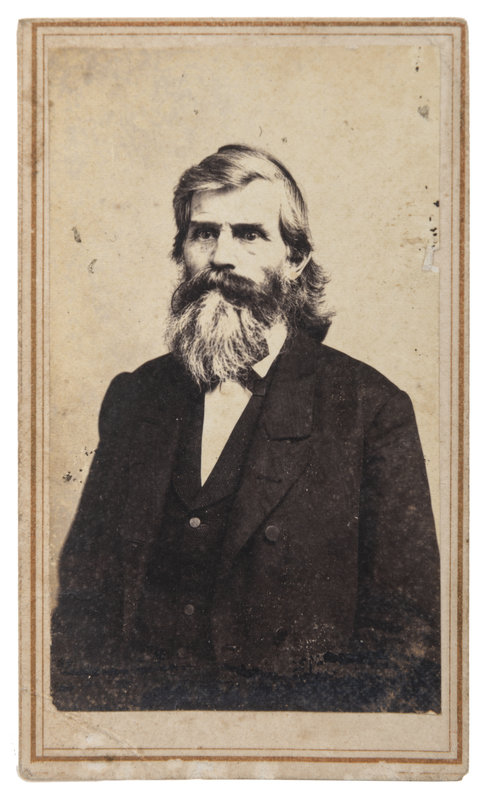

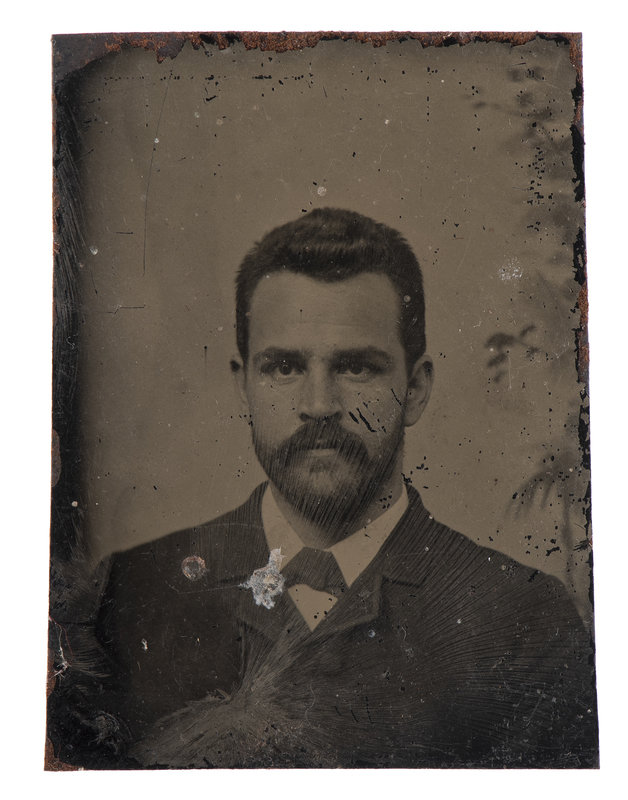

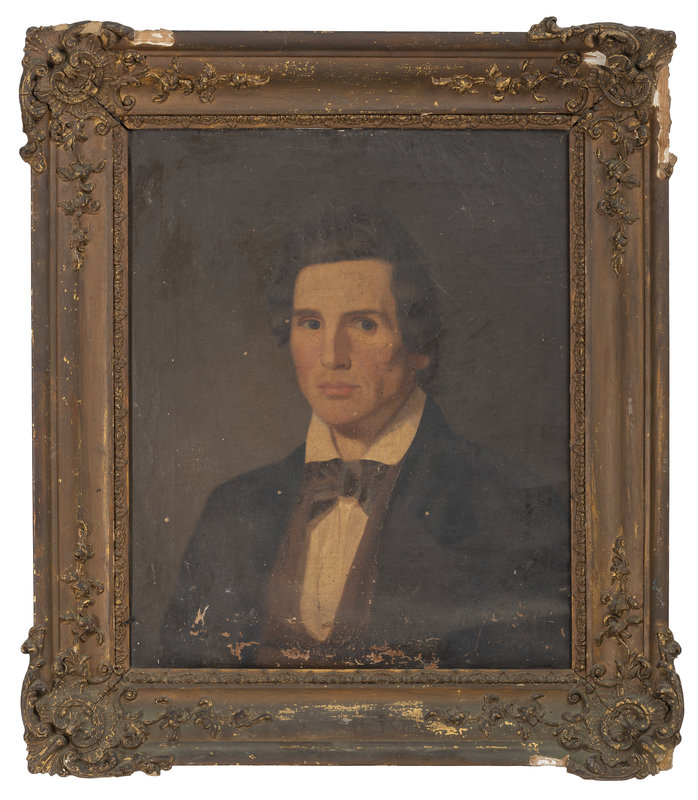

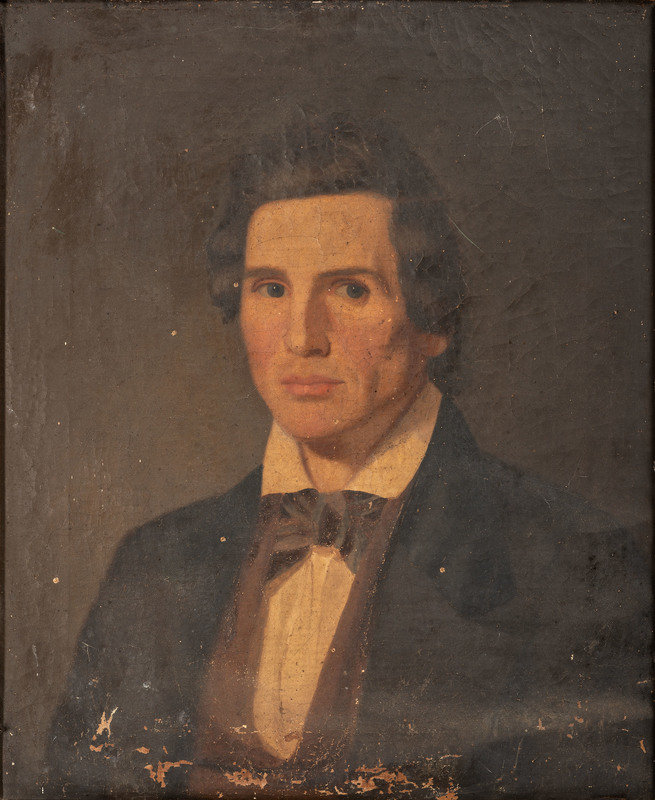

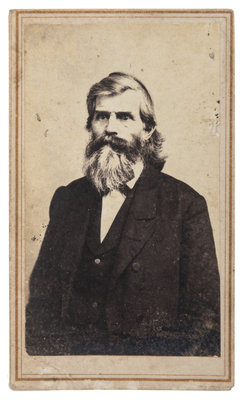

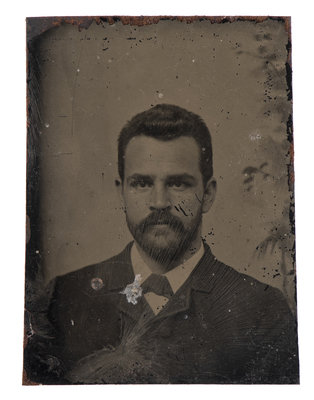

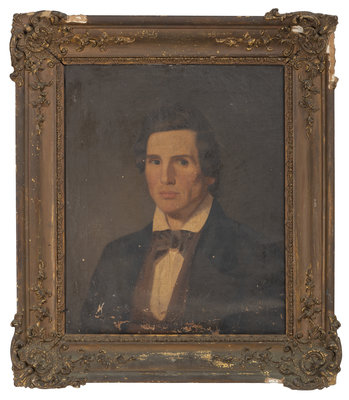

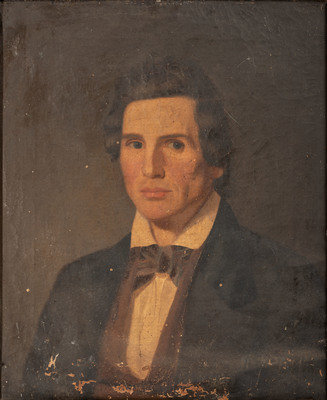

The collection also includes a carte de visite of Henry Fitz Jr. taken shortly before his death. New York: G.H. Morand. -- Gem tintype of Dr. George W. Fitz, photographer unknown, late 19th century. -- Oil painting of Henry Fitz. Jr. Artist unknown, ca 1840-1845. 19 x 23 1/2 in. (sight), framed dimensions 27 1/4 x 32 1/2 in. -- Oil painting of Julia Wells Fitz. Artist unknown, ca 1840-1845. 18 1/4 x 22 1/4 in., framed dimensions 26 1/2 x 30 1/2 in.

The collection also includes a carte de visite of Henry Fitz Jr. taken shortly before his death. New York: G.H. Morand. -- Gem tintype of Dr. George W. Fitz, photographer unknown, late 19th century. -- Oil painting of Henry Fitz. Jr. Artist unknown, ca 1840-1845. 19 x 23 1/2 in. (sight), framed dimensions 27 1/4 x 32 1/2 in. -- Oil painting of Julia Wells Fitz. Artist unknown, ca 1840-1845. 18 1/4 x 22 1/4 in., framed dimensions 26 1/2 x 30 1/2 in.

REFERENCES CITED

Becker, William B.

2014 “Man’s Perfect Image and Identity: Notes on an Early Daguerreotype of Henry Fitz Jr.” The Daguerreian Annual 2014: 214-216.

Foresta, Merry A. and John Wood

1995 Secrets of the Dark Chamber: The Art of the American Daguerreotype. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Fitz, Henry

1840 The Layman’s Legacy, or Twenty-five Sermons on Important Subjects. New York: P. Price. Volume 2: 316.

Johnson, John

1846 “Daguerreotype.” Eureka; or the National Journal of Inventions, Patents & Science. September 1846: 7-8; October 1846: 23-25.

1851 “An account of Wolcott and Johnson’s early experiments in the daguerreotype” IN: Samuel Dwight Humphrey, American Handbook of the Daguerreotype, 5th Ed. (New York, 1858), pp. 188-214, extracted from Humphrey’s Journal vol. II, 1851. (Accessed online, July 26, 2021, at (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/167/167-h/167-h.htm).

Johnson, Mark

2015 “Henry Fitz Jr.” A Portfolio of Open Research.” The Daguerreian Annual 2015: 148-163.

Kelbaugh, Ross J.

1998 “Dawn of the Daguerreian Era in Baltimore, 1839-1849.” The Daguerreian Annual 1998: 3-7.

Morse, Samuel F. B.

1839. New York Observer, May 18, 1839, as quoted in Welling 1978:7.

Newhall, Beaumont

1961 The Daguerreotype in America. Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

Root, Marcus Aurelius

1864 The Camera and the Pencil: Or the Heliographic Arts Its Theory And Practice In All Its Various Branches, E. G., Daguerreotype, Photography, Etc. Philadelphia.

Rinhart, Floyd and Marion

1981 The American Daguerreotype. The University of Georgia Press.

Sotheby’s

1999 The David Feigenbaum Collection of Southworth and Hawes. New York.

Taft, Robert W.

1938 Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839-1939. McMillan and Co.

Welling, William

1978 Photography in America: The Formative Years 1839-1900: 7-22. Thomas Crowell Company, New York.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Hindman gratefully acknowledges input from discussions from the following photographic historians, curators, and collectors: Rachel Wetzel, Photographic Conservator, Library of Congress shared many insights gleaned from her research on Robert Cornelius and other early Daguerreians. William Becker, Mark Johnson, and Leonard Walle share a long-standing interest in the contributions of Fitz to the development of the Wolcott camera and happily offered notes and encouragement. Ross Kelbaugh a long-time collector and photohistorian with a special interest in Maryland provided information relative to Fitz’ studio and history as a daguerreotypist in Baltmore. Denise Bethel, former head of the Photography Department at Sotheby’s and Keith Davis, Curator Emeritus of the Photography Department at the Nelson Atkins Museum shared their thoughts about the importance of the archive and provided important perspectives on its place in the marketplace.

I am indebted to Rachel Wetzel, Leonard Walle who read the manuscript with a critical eye. William Becker, a collector and photohistorian with a keen interest in Fitz, graciously read the manuscript and offered invaluable editorial suggestions and pointed out several errors.

Grant Romer, Curator of Photography Emeritus at the George Eastman Museum provided valuable perspectives on the collaboration between Wolcott, Johnson and Fitz. Mr. Romer also shared a photograph of the Wolcott mirror camera curated at the Dyer Library and Saco Museum in Saco, Maine.

C. Wesley Cowan Ph.D.

September, 2021